The most up-to-date version of this article can be found here - please click here!

Bowed string instruments have been played all over the world for many thousands of years.

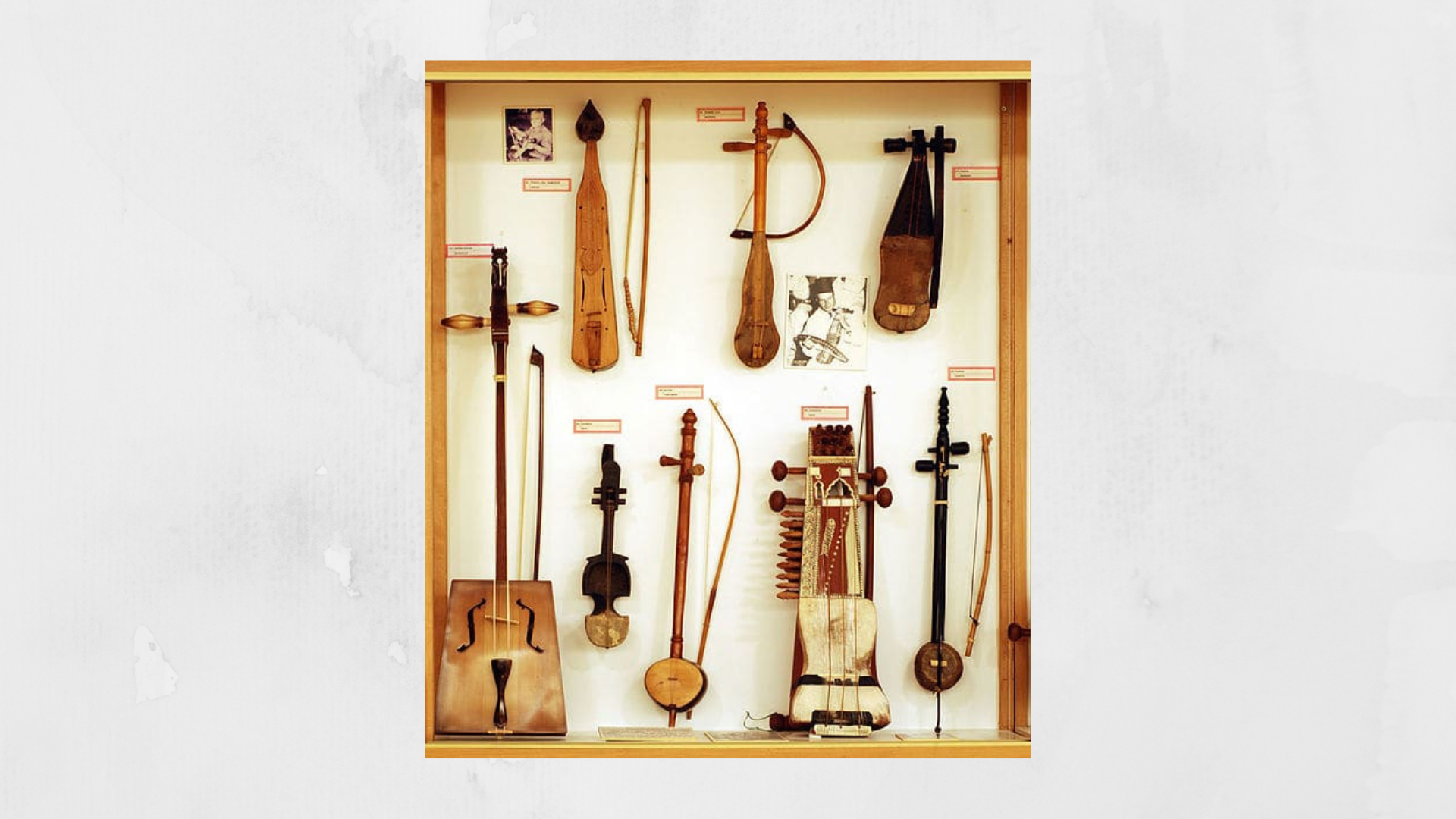

Medieval instruments including the Chinese erhu, the Finnish bowed lyre and the Indian sarangi all had the same basic mechanics as the modern violin, using the principle of a continually resonating string amplified by a hollow body.

In 7th century Greece, there was an instrument called the kithara, a seven stringed lyre, the features of which were very different from the violin.

Early Origins

The development of a musical instrument is rather like the process of evolution. It is gradual and complex, with many of its stages indistinct or undocumented. The history of the violin can be traced back more or less to the 9th century.

One plausible ancestor for the violin is the rabãb, an ancient Persian fiddle which was common in Islamic empires. The rabãb had two strings made of silk which were attached to an endpin and tuning pegs.

These strings were tuned in fifths. The instrument was fretless, its body made from a pear shaped gourd and a long neck.

It was introduced to Western Europe in the 11th and 12th centuries, and the influence of both the rabãb and lyre, along with a constant search for perfection and refinement and the demands of increasingly complex repertoire, led to the development of various European bowed instruments.

Ancestors of the Violin

Forerunners of the violin include the rebec, an instrument based on the rabãb, which appeared in Spain, most likely as a result of the Crusades.

The rebec had three strings and a wooden body and was played by resting it on the shoulder.

There were also Polish fiddles, the Bulgarian gadulka and Russian instruments called gudok and smyk, which are portrayed in frescos from the 11th century.

The 13th century French vielle was very different from the rebec. It had five strings and a larger body, which was closer in shape and size to the modern violin, with ribs shaped to allow for easier bowing.

Confusingly, the name vielle later came to refer to a different instrument, the vielle á rue, which we know as the hurdy-gurdy.

Emergence and Early Variants

There is no reference to the word violin until the reign of Henry VIII, but something very much like the violin existed, and its name was fydyl.

This instrument was played with a fydylstyck, proof that it was bowed and not plucked.

It had only three strings and a fretless fingerboard, and it was used for dancing, in banquets and social events; occasions which required an instrument with a strong sound, held shoulder height for projection.

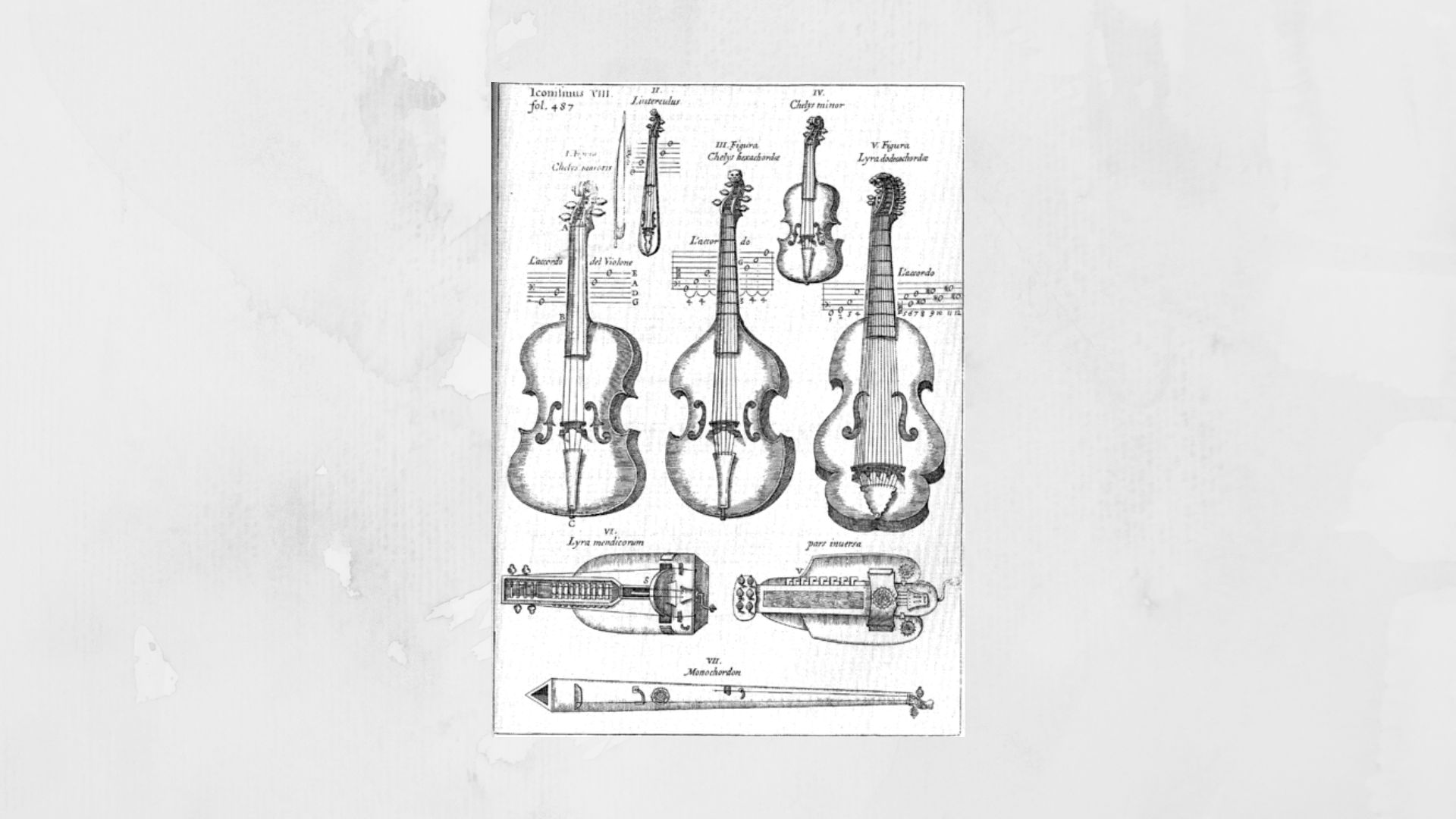

In 15th century Italy, two distinct kinds of bowed instruments emerged. One was fairly square in shape and held in the arms and was called a lira da braccio or viola da braccio, meaning viol of the arm.

This instrument had three strings and was the same general size and shape as the vielle, but the C-shaped sound holes in the body had been replaced by the now familiar F-holes.

The other bowed instrument was a viola da gamba, meaning viol for the leg.

The Rise of the Modern Violin

These gambas were important instruments during the Renaissance period, but were gradually replaced by the louder instruments of the less aristocratic lira da braccio family as the modern violin developed.

The violin first appeared in the Brescia area of Northern Italy in the early sixteenth century.

From around 1485, Brescia was home to a school of highly prized string players and famous for makers of all the string instruments of the Renaissance; the viola da gamba, violone, lyra, lyrone, violetta and viola da brazzo.

The word violin appears in Brescian documents for the first time in 1530, and whilst no instruments from the first decades of the fifteenth century survive, violins are shown in several paintings from the period.

Violins vs Viols

The first clear description of the violin, depicting its fretless appearance and tuning, was in the 1556 Epitome Musicale by Jambe de Fer.

By this time the violin had begun to spread throughout Europe. It was mainly used to perform dance music but was introduced into the upper classes as an ensemble instrument.

Where the viol, which was preferred in aristocratic circles, had been perfect for contrapuntal music and for accompanying the voice, the violin was normally played by professional musicians, servants and illiterate folk musicians.

| "The violin is very different from the viol. First, it has only four strings, which are tuned at a fifth from one to the other, and each of the said strings has four pitches in such wise that on four strings it has just as many pitches as the viol has on five.

It is smaller and flatter in form and very much harsher in sound, and it has no frets because the fingers almost touch each other from tone to tone in all the parts. Why do you call the former Viols, the latter Violins? We call viols those upon which gentlemen, merchants, and other persons of culture pass their time.The Italians call them "viole da gambe,” because they hold them at the bottom, some between the legs, others upon some seat or stool; others [support them] right on the knees of the said Italians, [but] the French make very little use of this method. The other kind [of instrument] is called "violin", and it is this that is commonly used for dance music [dancerie], and for good reason: for it is easier to tune, because the fifth is sweeter to the ear than the fourth is" It is, also easier to carry, which is a very necessary thing, especially in accompanying some wedding or mummery. The Italian calls it "violon da braccia" or "violone" because it is held upon the arms, some with a scarf, cord, or other thing. I did not put the said violin in a diagram, for you can consider it upon [the one for] the viol, joined [to the fact] that few persons are found who make use of it other than those who, by their labour on it, make their living." - Jambe de Fer from the Journal of the Viola Da Gamba Society of America, November 1967. |

The Evolution of the Modern Violin

The viola and cello developed alongside the violin in early 16th century Italy. This new family of stringed instruments gradually took the place of the gambas and viols as new ideas of sound emerged.

It is commonly accepted that the first modern violin was built by Andrea Amati, one of the famous luthiers (lute makers) of Cremona, in the first half of the 16th century.

The first four-stringed violin by Amati was dated 1555 and the oldest surviving of his instruments is from around 1560, but between 1542 and 1546, Amati also made several three-stringed violins.

Amati built his violins using a mould, which meant the measurements became much more precise. He developed a more vaulted shape for the body of the instrument rather than the flat soundboards of the early stringed instruments.

It is speculated that Amati may have studied with Gesparo da Salo in Brescia, but some records show that he was well established in Cremona long before he began making violins, and was in fact older than da Salo.

The Brescian school of luthiers had existed for 50 years before violin making began in Cremona, but the Cremona school gained prominence after 1630, when the bubonic plague swept Northern Italy and eliminated much of the Brescian competition.

Italy had managed to avoid the thirty-year war and development of the instrument continued in a golden age of culture.

Andrea Amati mastered many apprentices, and produced a dynasty of violinmakers, including the Guarneris, Bergonzis, and Rugeris.

His own sons followed him into the trade, and his grandson, Nicoló Amati, the most famous Amati, trained Antonio Stradivarius.

Stradivarius made over 100 instruments, of which roughly two thirds survive. His violins are some of the most imitated by modern makers today.

18th and 19th Century Transformations

The violin, originally an instrument of the lower classes, continued to gain popularity, becoming integral in the orchestra during the seventeenth century as composers such as Monteverdi began writing for the new string family.

The instrument continued to develop between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries, and the surviving historic violins have all undergone alterations.

The violin bow changed dramatically in around 1786, when Françoise Xavier Tourte invented the modern violin bow by changing the bend to arch backwards and standardising the length and weight.

The violin fingerboard was lengthened in the 19th century, to enable the violinist to be able to play the highest notes. The fingerboard was also tilted to allow more volume.

The neck of the modern violin was lengthened by one centimetre to accommodate the raising of pitch in the 19th century and the bass bar was made heavier to allow for greater string tension.

Where classical luthiers would fix the neck to the instrument by nailing and gluing it to the upper block of the body before attaching the soundboard, the neck of the modern violin is mortised to the body once it is completely assembled.

By the 18th and 19th century the violin had become extremely popular. By the late 18th century, makers had begun to use varnished developed to dry more quickly.

This had an impact on the quality of instruments produced. The quality of the wood used in violin making has been affected by the lack of purity of modern water as nearly all substances dissolved in water permanently penetrate wood.

By the 19th century violins were being mass-produced all over Europe. Millions were made in France, Saxony and the Mittenwald, in what is now Germany, Austria, Italy and Bohemia, now part of the Czech Republic.

It is partly for this reason that the violins of the early Italian masters are so prized, so well regarded and so expensive. A Stradivarius violin will now sell for many millions, the most expensive so far on record sold for $16million in 2011.

Modern Violins

More recently, new violins were invented for modern use. The Romanian Stroh violin used amplification like that of a gramophone to boost the volume.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, before electronic amplification became common, these violins with trumpet-like bells were used in the recording studio where a violin with a directional horn suited the demands of early recording technology better than a traditional acoustic instrument.

Electric and electro-acoustic violins have also been developed. An electro-acoustic violin may be played with or without amplification, but a solid bodied electric violin makes little or no sound without electronic sound reinforcement.

Electric violins can have as many as seven strings and can be used with equalisers and even sound effects pedals, a far cry from the exacting acoustic knowledge which created the great violins of the Italian Renaissance.

The violin is a string instrument with four strings, usually tuned in perfect fifths. It is the smallest member of the violin family, which includes viola, violoncello or ‘cello, and double bass, and has the highest pitch.

The violin, from the Medieval Latin word vitula, which means stringed instrument, was developed in its modern form in 16th Century Italy, and modified throughout the 18th and 19th Centuries. Also known as the fiddle, from the same root, the violin is played in a huge variety of Western music, from Baroque and Classical to Jazz, Folk and even Rock and Pop. It descends from remote ancestors that were used in folk music and played throughout Asia, Europe and the Americas.

The violin was initially a poor-man’s instrument, popular with gypsies and in Jewish culture, easily hand made and robust. There are hundreds of shapes, sizes and designs of these rustic folk instruments throughout the world.

The Chinese fiddle, or Erhu, is a remote ancestor of the violin.

… and the violin is also found in India, where the instrument is the same as a Western violin but the technique of playing differs, with the violin balanced between the left shoulder and the right foot.

The violin is normally tuned to the pitches G, D, A and E, but in Indian music it can be tuned D#, A#, D#, A# and many other pitches are used. In Baroque music and in British and Irish folk music this technique, which is called scordatura, literally meaning mistuning, is frequently used to create entirely different tonalities and harmonic effects.

Making a Violin

The parts of the violin are made from different types of wood. Its sound is dependent on the specific acoustic characteristics of its shape. Sound is produced when a bow is drawn across the strings, or when the string is plucked, causing it to vibrate.

The top of the violin, which is also called the belly or soundboard is made of spruce. The back and ribs are made from maple or sycamore. The best wood for violin making has been seasoned for many years, and the seasoning process continues indefinitely after the violin is made.

The voice of the violin depends on its shape, the quality of its wood, and its varnish. Wood that has grown too quickly in lush environments is considered less resonant, and there is a romantic belief that wood from trees grown in high altitudes and poor conditions produces the best violins.

There has been a huge amount of speculation into the techniques of the Italian master violin-makers of the 17th Century, Stradivarius and Guarnari, whose violins are now investment items selling for many millions of pounds.

This short film explains some possible differences in the wood and varnish preparation, which have created such fine instruments.

The violin is glued with animal hide glue, a soft adhesive that can easily be removed if repairs are needed. The softness of the glue also allows for expansion and contraction of the wood and means that the violin is more likely to come unglued in extreme conditions than for the wood to split. The purfling, the decorative inlay around the body of the violin, is actually designed to protect the edges of the wood from cracking and allows the belly of the violin to flex independently of the ribs.

The arched body with its hourglass shape and curved bouts is essential for the tone. The shape of the instrument is designed to withstand the stress of use and the tensions of the strings, and these curved shapes also give it aesthetic beauty. The design of the violin was influenced by Renaissance philosophies, and results from a fusion of mathematical, aesthetic and scientific principles, not least the Pythagorean teaching that beauty is the result of perfect number ratios.

The neck of the violin is normally made from maple, with an ebony fingerboard. Ebony is used for its hardness and resistance to wear. The neck ends in a peg box and a carved scroll, the fineness of which is often used as an indication of the skill of the violin maker.

This storyboard by Chicago violin shop Fritz Reuter, shows a simple step-by-step illustration of the violin making process.

Why Choose the Violin?

In his book Life Class, Yehudi Menuhin describes the affinity some people have for the violin, explaining that it is not only a melodic instrument, it is also immediately tactile and accessible, even to a child. The violin can be purchased in many different sizes suitable for even the smallest child. These small violins, which can be as tiny as 1/62nd of a full size instrument, are not finely made as they are designed to be resilient for beginners to use, but can be picked up, as Menuhin describes, as easily as a child picks up a teddy bear.

“A child who has a direct natural inclination for the violin has something of an advantage in choosing this instrument over others,” he says. “It is rather like the voice, is a much more tactile instrument than many others and can come in a variety of sizes.

This picture from thesoundpost.co.uk shows the common sizes of beginner instruments for children of different ages.

Menuhin ascribes the appeal of the violin mainly to its sound, which is like that of the human voice.

“With the violin you have to make your own sound and pitch. It is your own voice you are projecting or …learning to project.” He explains that this is why it is possible to distinguish the sounds, tone and styles of different violinists. Playing the violin involves the whole body and this gives the violin the greatest and most immediate range of expression of any instrument.

This playfulness and expression can be seen in this video of a young Sarah Chang playing Sarasate’s Carmen Fantasy.

“I look to the child who, with the child’s confidence, is willing to take up the fiddle, to play it and to play with it, to explore its infinite range of tones and qualities until he finds that voice which is uniquely his own.” Yehudi Menuhin

Karl Jenkins is a Welsh composer and musician, born in 1944. He started his musical career as an oboist in the National Youth Orchestra of Wales and studied as a postgraduate at the Royal Academy of Music. He went on to work mainly in jazz and jazz-rock bands, on baritone and soprano saxophone, keyboard, and oboe; an unusual instrument in jazz music.

Jenkins’ compositions are amongst some of the most popular around. His choral work The Armed Man was listed no.1 in Classic FM's Top 10 by Living Composers, 2008 and his work has featured in adverts for international companies including Levi Jeans, Renault and De Beers.

The Palladio Suite, one of Jenkins’ most famous works, is written in the Concerto Grosso style more commonly associated with Baroque music. It is made up of three movements; Allegretto, Largo and Vivace; and harks back to the writing of Venetian composers such as Vivaldi and Albinoni. It is conventional and unchallenging, its techniques and harmonies remaining firmly based in the 18th Century, a feature which is unusual for Jenkins who often combines a mixture of modern and traditional musical styles in his work.

Palladio was inspired by the architect Andrea Palladio, who designed many beautiful villas and churches in the Venice region in the 16th Century, and who gives his name to the London Palladium. The piece mirrors the idea of artistic beauty within a defined architectural framework.

This is not the only time Jenkins has found a connection between his music and visual aesthetics. On the front page of his website he tells the following story:

“Very late one night in 1997, across a dark and deserted St. Mark’s Square, Venice, I saw a painting, lit like a beacon, drawing me inexorably to the window of Galleria Ravagnan. It made a deep impression on me and as my wife and fellow musician, Carol, remarked, it looked like my music sounded. I simply had to have it so I returned the next day, bought the painting and began a long friendship with gallery owner Luciano Ravagnan. On a return visit, a year or so later, I met and befriended the artist only for us both to discover that he, not knowing who had bought his painting, had been painting to my music!”

The first movement of the Palladio Suite, Allegretto, is the most frequently performed. It became well known initially as the music for the 1994 De Beers Diamond advert. It has been recorded by the electric string quartets, Bond and Escala, and has established a permanent position in Classic FM’s Hall of Fame.

The movement is constructed from rigid, repetitive string lines, which exist as building blocks over a staccato bass line, driving an ever-developing sense of drama and intensity.

It is important when playing this movement to subdivide the bars so as not to rush. You can hear how the parts interject and answer each other, but do so within a tight rhythmic framework. The rests are just as important as the notes and a combination of good counting, strong pulse and listening will help the ensemble. Try listening along with the score to see how the parts weave together and bounce off each other.

The bow-stroke in this movement should be clean, with plenty of contact, in the middle to lower-middle part of the bow. Each gesture of the main rhythmic figure works well from an up-bow. The tightly interwoven harmonies require clear intonation and a ringing tone to recreate the openness of the Venetian Baroque sound world.

The Suite has two further movements, both of which are immediately reminiscent of Vivaldi’s Violin Concerto, Winter from The Four Seasons.

The Largo features a pulsating accompaniment and a soaring, wistful violin solo, in which parallels with Vivaldi’s Largo are strongly apparent.

The Vivace is much lighter and more delicate than the Allegretto, with an immediately Baroque sound. Imagine how a lighter baroque bow would feel. You can do this by holding your own bow higher up the stick away from the frog. This will give you an idea of the lightness and vivacity of bow stroke necessary to bring the Vivace to life.

Again, it is easy to recall the nervous energy of the third movement of Vivaldi’s Winter. The insistent quality in the staccato, accompanying figure, the use of ostinato, which Jenkins frequently favours, and the minor tonality are common to both the Vivaldi and the third movement of Palladio.

The popular first movement has been recorded countless times by a diverse spectrum of musicians, given thousands of minutes of airtime on Classic FM and even remixed as a Dubstep song, but which recording is the best?

Classic FM recommends The Smith Quartet: London Philharmonic Strings Conducted by Karl Jenkins – Sony SK62276, or if you fancy something more up-tempo, try the recording by electric string quartet Escala.

Interestingly, both versions only feature the first movement. The complete suite is available on Jenkins’ 1996 album, the aptly named Diamond Music, featuring the Smith Quartet and the London Philharmonic Orchestra.

Recordings on YouTube are also mainly restricted to the famous first movement, neglecting the others, despite their rather delicate beauty. This echoes another phenomenon of popular Baroque music whereby one movement becomes favoured, perhaps due to exposure in television, film or advertising. The first movement of Vivaldi’s Spring has become more popular than its other movements, and everybody thinks Pachelbel only wrote one tune.