The most up-to-date version of this article can be found here - please click here!

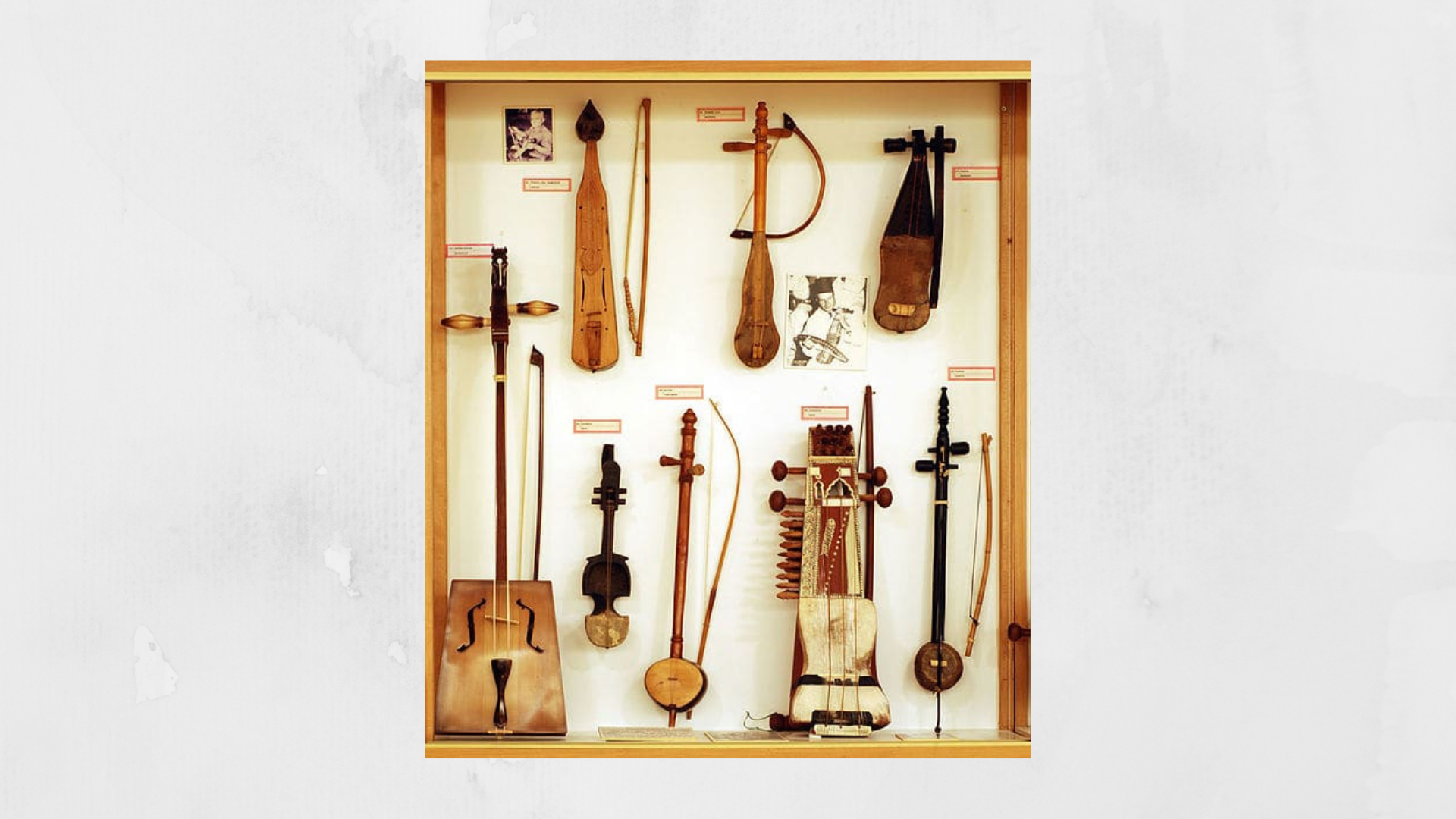

Bowed string instruments have been played all over the world for many thousands of years.

Medieval instruments including the Chinese erhu, the Finnish bowed lyre and the Indian sarangi all had the same basic mechanics as the modern violin, using the principle of a continually resonating string amplified by a hollow body.

In 7th century Greece, there was an instrument called the kithara, a seven stringed lyre, the features of which were very different from the violin.

Early Origins

The development of a musical instrument is rather like the process of evolution. It is gradual and complex, with many of its stages indistinct or undocumented. The history of the violin can be traced back more or less to the 9th century.

One plausible ancestor for the violin is the rabãb, an ancient Persian fiddle which was common in Islamic empires. The rabãb had two strings made of silk which were attached to an endpin and tuning pegs.

These strings were tuned in fifths. The instrument was fretless, its body made from a pear shaped gourd and a long neck.

It was introduced to Western Europe in the 11th and 12th centuries, and the influence of both the rabãb and lyre, along with a constant search for perfection and refinement and the demands of increasingly complex repertoire, led to the development of various European bowed instruments.

Ancestors of the Violin

Forerunners of the violin include the rebec, an instrument based on the rabãb, which appeared in Spain, most likely as a result of the Crusades.

The rebec had three strings and a wooden body and was played by resting it on the shoulder.

There were also Polish fiddles, the Bulgarian gadulka and Russian instruments called gudok and smyk, which are portrayed in frescos from the 11th century.

The 13th century French vielle was very different from the rebec. It had five strings and a larger body, which was closer in shape and size to the modern violin, with ribs shaped to allow for easier bowing.

Confusingly, the name vielle later came to refer to a different instrument, the vielle á rue, which we know as the hurdy-gurdy.

Emergence and Early Variants

There is no reference to the word violin until the reign of Henry VIII, but something very much like the violin existed, and its name was fydyl.

This instrument was played with a fydylstyck, proof that it was bowed and not plucked.

It had only three strings and a fretless fingerboard, and it was used for dancing, in banquets and social events; occasions which required an instrument with a strong sound, held shoulder height for projection.

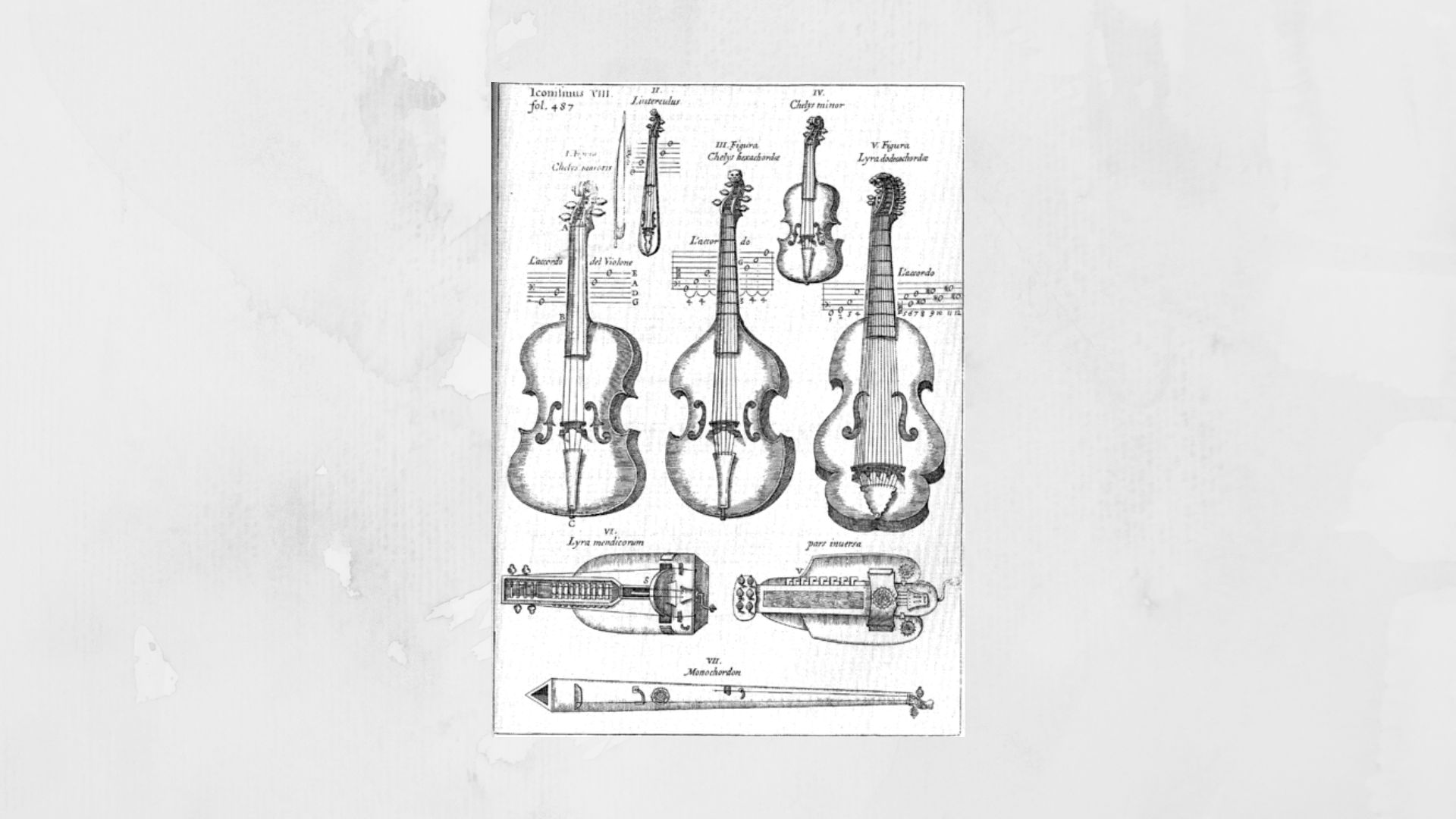

In 15th century Italy, two distinct kinds of bowed instruments emerged. One was fairly square in shape and held in the arms and was called a lira da braccio or viola da braccio, meaning viol of the arm.

This instrument had three strings and was the same general size and shape as the vielle, but the C-shaped sound holes in the body had been replaced by the now familiar F-holes.

The other bowed instrument was a viola da gamba, meaning viol for the leg.

The Rise of the Modern Violin

These gambas were important instruments during the Renaissance period, but were gradually replaced by the louder instruments of the less aristocratic lira da braccio family as the modern violin developed.

The violin first appeared in the Brescia area of Northern Italy in the early sixteenth century.

From around 1485, Brescia was home to a school of highly prized string players and famous for makers of all the string instruments of the Renaissance; the viola da gamba, violone, lyra, lyrone, violetta and viola da brazzo.

The word violin appears in Brescian documents for the first time in 1530, and whilst no instruments from the first decades of the fifteenth century survive, violins are shown in several paintings from the period.

Violins vs Viols

The first clear description of the violin, depicting its fretless appearance and tuning, was in the 1556 Epitome Musicale by Jambe de Fer.

By this time the violin had begun to spread throughout Europe. It was mainly used to perform dance music but was introduced into the upper classes as an ensemble instrument.

Where the viol, which was preferred in aristocratic circles, had been perfect for contrapuntal music and for accompanying the voice, the violin was normally played by professional musicians, servants and illiterate folk musicians.

| "The violin is very different from the viol. First, it has only four strings, which are tuned at a fifth from one to the other, and each of the said strings has four pitches in such wise that on four strings it has just as many pitches as the viol has on five.

It is smaller and flatter in form and very much harsher in sound, and it has no frets because the fingers almost touch each other from tone to tone in all the parts. Why do you call the former Viols, the latter Violins? We call viols those upon which gentlemen, merchants, and other persons of culture pass their time.The Italians call them "viole da gambe,” because they hold them at the bottom, some between the legs, others upon some seat or stool; others [support them] right on the knees of the said Italians, [but] the French make very little use of this method. The other kind [of instrument] is called "violin", and it is this that is commonly used for dance music [dancerie], and for good reason: for it is easier to tune, because the fifth is sweeter to the ear than the fourth is" It is, also easier to carry, which is a very necessary thing, especially in accompanying some wedding or mummery. The Italian calls it "violon da braccia" or "violone" because it is held upon the arms, some with a scarf, cord, or other thing. I did not put the said violin in a diagram, for you can consider it upon [the one for] the viol, joined [to the fact] that few persons are found who make use of it other than those who, by their labour on it, make their living." - Jambe de Fer from the Journal of the Viola Da Gamba Society of America, November 1967. |

The Evolution of the Modern Violin

The viola and cello developed alongside the violin in early 16th century Italy. This new family of stringed instruments gradually took the place of the gambas and viols as new ideas of sound emerged.

It is commonly accepted that the first modern violin was built by Andrea Amati, one of the famous luthiers (lute makers) of Cremona, in the first half of the 16th century.

The first four-stringed violin by Amati was dated 1555 and the oldest surviving of his instruments is from around 1560, but between 1542 and 1546, Amati also made several three-stringed violins.

Amati built his violins using a mould, which meant the measurements became much more precise. He developed a more vaulted shape for the body of the instrument rather than the flat soundboards of the early stringed instruments.

It is speculated that Amati may have studied with Gesparo da Salo in Brescia, but some records show that he was well established in Cremona long before he began making violins, and was in fact older than da Salo.

The Brescian school of luthiers had existed for 50 years before violin making began in Cremona, but the Cremona school gained prominence after 1630, when the bubonic plague swept Northern Italy and eliminated much of the Brescian competition.

Italy had managed to avoid the thirty-year war and development of the instrument continued in a golden age of culture.

Andrea Amati mastered many apprentices, and produced a dynasty of violinmakers, including the Guarneris, Bergonzis, and Rugeris.

His own sons followed him into the trade, and his grandson, Nicoló Amati, the most famous Amati, trained Antonio Stradivarius.

Stradivarius made over 100 instruments, of which roughly two thirds survive. His violins are some of the most imitated by modern makers today.

18th and 19th Century Transformations

The violin, originally an instrument of the lower classes, continued to gain popularity, becoming integral in the orchestra during the seventeenth century as composers such as Monteverdi began writing for the new string family.

The instrument continued to develop between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries, and the surviving historic violins have all undergone alterations.

The violin bow changed dramatically in around 1786, when Françoise Xavier Tourte invented the modern violin bow by changing the bend to arch backwards and standardising the length and weight.

The violin fingerboard was lengthened in the 19th century, to enable the violinist to be able to play the highest notes. The fingerboard was also tilted to allow more volume.

The neck of the modern violin was lengthened by one centimetre to accommodate the raising of pitch in the 19th century and the bass bar was made heavier to allow for greater string tension.

Where classical luthiers would fix the neck to the instrument by nailing and gluing it to the upper block of the body before attaching the soundboard, the neck of the modern violin is mortised to the body once it is completely assembled.

By the 18th and 19th century the violin had become extremely popular. By the late 18th century, makers had begun to use varnished developed to dry more quickly.

This had an impact on the quality of instruments produced. The quality of the wood used in violin making has been affected by the lack of purity of modern water as nearly all substances dissolved in water permanently penetrate wood.

By the 19th century violins were being mass-produced all over Europe. Millions were made in France, Saxony and the Mittenwald, in what is now Germany, Austria, Italy and Bohemia, now part of the Czech Republic.

It is partly for this reason that the violins of the early Italian masters are so prized, so well regarded and so expensive. A Stradivarius violin will now sell for many millions, the most expensive so far on record sold for $16million in 2011.

Modern Violins

More recently, new violins were invented for modern use. The Romanian Stroh violin used amplification like that of a gramophone to boost the volume.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, before electronic amplification became common, these violins with trumpet-like bells were used in the recording studio where a violin with a directional horn suited the demands of early recording technology better than a traditional acoustic instrument.

Electric and electro-acoustic violins have also been developed. An electro-acoustic violin may be played with or without amplification, but a solid bodied electric violin makes little or no sound without electronic sound reinforcement.

Electric violins can have as many as seven strings and can be used with equalisers and even sound effects pedals, a far cry from the exacting acoustic knowledge which created the great violins of the Italian Renaissance.

Learning the violin is a life journey. Whatever attracted you to start, whether it was a particular performance, the uniquely beautiful sound of the violin, a desire to learn a new skill or the fact you had always wanted to play an instrument, there’s a lot of fun ahead. For more advanced students too, as you deepen your relationship with the instrument and the repertoire, there is always more to learn.

Progress takes diligence and patience, but there are certain things you can do that will keep you on the right track. These ten violin-playing tips can be followed at every level of playing and will have a really positive impact on your experience of the violin. Treat yourself to an immersive, holistic learning journey. If you’re stuck, if your practice feels stagnant, or progress has ground to a halt, use these ten tips as a checklist for progress.

There are many low-cost student violin kits on the market, and some of them are really horrible! They sound bad, look cheap, and even the most experienced professional would find them hard to play. Shop around for the best instrument you can afford. Nobody expects you to turn up to your first lesson, or even your 101st lesson, with a Stradivarius, but you will learn better if the violin works well.

There are plenty of good student sets too, and an experienced luthier will be able to improve a low-cost instrument by refining the set-up. Ask your teacher’s advice before buying a violin and talk to your violin shop about fitting a good violin bridge. If you don’t want to commit straight away, many dealerships offer rental options while you look around for the right violin to buy.

The cost of violin lessons can seem high, but one-to-one time with an experienced tutor is invaluable. Your teacher will assess where you are in the learning process and which skills you need to work on. A skilled musician will direct your learning and identify problems before you develop bad habits. One-to-one lessons offer a great opportunity for development. Modern technology gives the opportunity to have wonderful learning experiences wherever you are in the world. Many students now have violin lessons over Skype with their teacher in a different city or even continent.

Nowadays, many learners take lessons via webcam using software such as Skype.

Daily practise WILL lead to progress. Yes, there’s the research that says it takes 10,000 hours to master a skill, but don’t feel you have to practise for hours every day to see improvement. Much more important is HOW you practise. Work undertaken with focused concentration pays off, but mindless repetition can actually set you back. Study in small time-blocks with lots of breaks, maintaining an awareness of your focus. Before repeating a task, identify where the problem is and what you are aiming to change.

It takes a lot of brainpower to play the violin, but ultimately you make the sound by moving your body. Do some simple warm-up stretches before practising and keep a spot check of your posture throughout the session. Notice any areas of tension, analyse what is causing them (I’m clenching my jaw because I am trying too hard; I’m raising my right shoulder because I’m worried I will drop the bow). If you can’t release the tension by yourself, ask your teacher’s advice. Many problems can be resolved by simply remembering to breathe and maintaining awareness.

A flexible, well-balanced body posture is essential for good violin-playing.

When learning how to manage the violin physically, it is sometimes hard to concentrate on how you sound. And because the violin is placed so close to the left ear, it is not always easy to get a real sense of how the performance sounds to others. Record your practise as often as you can. Listen back, looking for positives as well as points you want to improve.

Whatever repertoire you are learning, it is really important to listen to the piece. By listening to other violinists, not only will you develop a well-rounded idea of your piece, you will develop your ear. Passive listening (listening away from your instrument) can improve pitch, tone and phrasing, while active listening (with the music in front of you and the violin or an air violin in your hand) can actually trigger physical improvements and musical insights. For example, miming your bowing along with a section of a recording can deepen your muscle memory of that bowing, and help identify problem areas. There are literally thousands of videos and recordings available on YouTube, featuring some of the greatest violinists who ever lived. Sometimes you can even get ideas for fingerings and bowings by watching your favourite soloist play!

Technical exercises and scales are the building blocks of violin music. Working on these simple patterns out of context of the repertoire gives an opportunity to improve intonation and tone production across the board. Scales also help teach an understanding of key. You’ll find loads of scales and technical exercises in our resource library.

All music, no matter how simple, comes with some historical and social context. Is your piece based on a dance or a song? Who was the composer, and when was it written. For more substantial pieces, it can be interesting to find out why the work was composed and what was going on in the composer’s life at the time. If someone had fallen in love or was suffering from depression, those feelings will be reflected in the music and might inform how you choose to express certain phrases.

A major reason we get nervous during performance is because it is an unfamiliar situation and therefore fraught with pressure. Practise performing, either by simulating performances where you play your piece without stopping to an armchair full of teddy bears or smart phone microphone, or set up performance opportunities with friends. Integrate the act of performing into your preparation and it will soon feel natural.

To give a good performance, you need to practise performing! Make performance practice part of your regular practice habits.

It is easy to panic and feel stressed if things are not going to plan. Whatever your age or playing level, a bad practise session can feel like a personal disaster. If your practise is really going badly, stop! Take a break, go for a short walk, try some breathing exercises or have a glass of water. Never pick up your violin expecting it to feel the same as it did yesterday, that would be like walking into a room and finding everyone in the exact same mood they were the day before.

Begin where you are today, with a sense of exploration. If something will not go right, break it down to open strings, practise some slow bows or go back to relaxed scales.

The violin is traditionally built as an acoustic instrument. The shape of the body is designed purely to produce and amplify the sound created by the vibrations of the strings. However, since the American jazz clubs of the 1920s, modern popular music genres have created the need for violins that can be amplified beyond the normal capabilities of the instrument.

There are various different ways to create an electronically amplified sound for the violin. Some musicians argue that the best tone is produced with an acoustic violin and a specialised microphone, but this can sometimes create feedback and amplify unwanted sounds, as noise from a loud room will resonate inside the body of the violin and pass back into the microphone.

Another way to amplify the violin is with an electric piezo pickup, which is a small transducer in contact with the body or bridge of the violin, designed to amplify only the sound created by the violin. A violin modified with a pickup is referred to as an electro-acoustic violin.

Electro-acoustic violins are often custom built, as most violinists are nervous of applying a contact pickup to the varnish or bridge of their best instrument. They can still be played as acoustic instruments, although the extra weight of the pickup can make them less comfortable to use, and the pickup itself on the body of the violin can mute the sound slightly by dampening the vibrations.

The first use of electronically amplified violins was in jazz music. The jazz violinist Stuff Smith (1909 -1967) who is featured in several trio numbers on Nat King Cole’s album After Midnight, is thought to have been the first violinist to experiment with adapting the violin with pickups. His better-known counterpart, Stephane Grappelli (1908 – 1997) apparently struggled to find a solution to the need for amplification.

There is a gap of fifteen years between 1956 and 1971 in Grappelli’s discography; a time when he barely recorded anything. This is thought to be due to the technical developments in jazz music at the time. Electric guitars, improved microphones and bigger brass sections made it hard for the violin to compete, and Grappelli was dissatisfied with the results of his experiments with amplification as they had a destructive effect on the unique, gentle timbres of the violin. He tried out lots of different things, one of which was an early electric violin.

In an interview with Max Jones of the London Melody Maker in November of 1952, Grappelli declares of the electric violin, "Now the Violin Can Find a Real Place in Jazz . . ." It possible he was either testing or endorsing the instrument as his enthusiasm is not followed up with any noted performances or recordings on the violin. The article continues:

"In his Variety act with pianist Yorke de Sousa, Grappelly [he often used this misspelling as it was preferable to the alternative mispronunciation] still uses his standard violin. But for dances and jazz sessions his improvisations are now amplified directly he puts bow to steel strings. He is an enthusiastic exponent of the electric violin - an American instrument that radio listeners heard for the first time in World of Jazz on November 1.

'Of course the instrument's full value cannot be realized from a record or broadcast, because the amplifier isn't really needed then. The tone sounds different, yes; but you must hear this violin in a hall to get the whole effect. It is wonderful.'

The wonder instrument is a curious sawn-off looking thing, visually unimpressive and extraordinarily heavy. We wanted to know if it demanded a special technique.

'The fingerboard is the same, but it has to have metal strings. For me, the finger- pressure is about the same as I normally use, but the bowing is different. This needs great control. You must have very steady bowing, for every little sound is enlarged through the loudspeaker. Each time I am going to use the electric fiddle I must get used to it again; I must play all day. It isn't easy to play well at first, but once you have mastered this fiddle it is fantastic. This fiddle is definitely better than the normal one for jazz playing; there is no comparison. For solos it is powerful and exciting. It means that the violin can take a full part in the jazz orchestra at last. It's no longer a little voice; it's more like four fiddles. I mean, I may play louder than four fiddles, but, of course, the sound is not the same. In fact, it is an entirely new sound, and eventually it will add new tone colour to jazz recordings, too.’”

Melody Maker November 15th 1952

The instrument Grappelli was talking about was made by the American company Vega, who were manufacturing electric violins from as early as 1939.

The American company, Fender, which is famous for its electric guitars, also produced some of the early electric violins, with the first model appearing in 1958.

As we can see from this interview with Grappelli, and from the Vega advert, even by 1939, the electric violin was a very heavily modified version of the violin.

The modern electric violin, most accurately described, is an instrument almost entirely distinct from the violin, with built-in pickups and a solid body.

The body of the electric violin is solid for three reasons:

The shape of the electric violin is modified to be as minimalistic as possible, to keep the weight of the body from becoming too great. Materials used to build the body include carbon fibre, Kevlar and glass, although performers increasingly customise and embellish their instruments, as demonstrated by these two Swarovski Crystal encrusted instruments belonging to electric violin duo Fuse. For more information please visit www.fuseofficial.com or www.electricstringquartet.com"

Fuse also commissioned two 24 carat gold plated violins, which are each insured for £1.35 million.

The electric violin is still seen as a somewhat experimental instrument. It is much less established than the electric guitar or bass, and produces very different results from the best acoustic violins. There are many variations on the standard design. Some instruments have frets, extra strings, guitar heads instead of violin pegs and sympathetic strings.

It is also not unusual for an electric violin to have five, six, seven or more strings. Dutch violinmaker Yuri Landman built a 12 string electric violin for the Belgian band DAAU. The strings on this instrument are clustered in four groups of three strings tuned unison creating a chorus.

The extra strings on these multiple-stringed violins are usually a low C string on a five-string, which gives an instrument which can serve simultaneously as a violin and viola, a low C and low F on a six-string, and a low C, F and B♭ for strings.

The amplification signals for the electric violin pass through electronic processing in the same way for the electric guitar. The audio output is transferred through an audio cable into an amp or PA. Most electric violinists use a standard guitar amp, which will be reliable but may not give the best tone for the violin. Few amps exist specifically for the electric violin. Effects pedals that create delay, reverb, chorus and distortion can be used to create variations on the traditional sound. Electric violins may use magnetic, piezoelectric, or electrodynamic pickups, the most common and inexpensive of which are the piezoelectric pickups. Piezo elements detect physical vibrations directly. They are placed in or on the body of the violin, or more commonly they take their output from the vibrations of the bridge. These pickups have a high output impedance, which means they must be plugged into a high impedance input stage in the amplifier, or go through a powered preamp. This matches the signal to avoid any problems with low frequency loss and microphone noise pickup.

There are increasing numbers of electric violins to choose from, and various companies that produce their own version of the instruments. They are ideal for pop and rock music. With the correct pedals and equipment they produce a huge range of sounds and effects, and they also create a modern image, which fits better than a traditional violin in certain settings. The sound is not as sophisticated as the acoustic violin, and levels of expression and nuance are more electronic than imitative of the human voice. However, the electric violin particularly gives the opportunity to experiment with multiple combinations of strings and instrumentation, which is not possible on an acoustic instrument. It is also great for silent practice.

For those purists who love the sound of the violin, the electric violin is a long way from replacing the violin’s sheer beauty of sound, but there is an increasing market for electric violin music, and several popular artists and groups have based their careers entirely around the versatilities of the instruments, as well as many musicians who have integrated the range of the electric violin into their repertoire. In fact, electric violin makers often work with violinists to produce newer and better solutions to the musician’s needs. Instruments can be really personalised.

The electric violin is still an instrument in the developmental stages, but the demands of musicians wanting the perfect combination of versatility and sound quality will continue to improve its status and desirability. It will never replace the violin, but the electric violin is gaining its own place in music.

The violin is a string instrument with four strings, usually tuned in perfect fifths. It is the smallest member of the violin family, which includes viola, violoncello or ‘cello, and double bass, and has the highest pitch.

The violin, from the Medieval Latin word vitula, which means stringed instrument, was developed in its modern form in 16th Century Italy, and modified throughout the 18th and 19th Centuries. Also known as the fiddle, from the same root, the violin is played in a huge variety of Western music, from Baroque and Classical to Jazz, Folk and even Rock and Pop. It descends from remote ancestors that were used in folk music and played throughout Asia, Europe and the Americas.

The violin was initially a poor-man’s instrument, popular with gypsies and in Jewish culture, easily hand made and robust. There are hundreds of shapes, sizes and designs of these rustic folk instruments throughout the world.

The Chinese fiddle, or Erhu, is a remote ancestor of the violin.

… and the violin is also found in India, where the instrument is the same as a Western violin but the technique of playing differs, with the violin balanced between the left shoulder and the right foot.

The violin is normally tuned to the pitches G, D, A and E, but in Indian music it can be tuned D#, A#, D#, A# and many other pitches are used. In Baroque music and in British and Irish folk music this technique, which is called scordatura, literally meaning mistuning, is frequently used to create entirely different tonalities and harmonic effects.

Making a Violin

The parts of the violin are made from different types of wood. Its sound is dependent on the specific acoustic characteristics of its shape. Sound is produced when a bow is drawn across the strings, or when the string is plucked, causing it to vibrate.

The top of the violin, which is also called the belly or soundboard is made of spruce. The back and ribs are made from maple or sycamore. The best wood for violin making has been seasoned for many years, and the seasoning process continues indefinitely after the violin is made.

The voice of the violin depends on its shape, the quality of its wood, and its varnish. Wood that has grown too quickly in lush environments is considered less resonant, and there is a romantic belief that wood from trees grown in high altitudes and poor conditions produces the best violins.

There has been a huge amount of speculation into the techniques of the Italian master violin-makers of the 17th Century, Stradivarius and Guarnari, whose violins are now investment items selling for many millions of pounds.

This short film explains some possible differences in the wood and varnish preparation, which have created such fine instruments.

The violin is glued with animal hide glue, a soft adhesive that can easily be removed if repairs are needed. The softness of the glue also allows for expansion and contraction of the wood and means that the violin is more likely to come unglued in extreme conditions than for the wood to split. The purfling, the decorative inlay around the body of the violin, is actually designed to protect the edges of the wood from cracking and allows the belly of the violin to flex independently of the ribs.

The arched body with its hourglass shape and curved bouts is essential for the tone. The shape of the instrument is designed to withstand the stress of use and the tensions of the strings, and these curved shapes also give it aesthetic beauty. The design of the violin was influenced by Renaissance philosophies, and results from a fusion of mathematical, aesthetic and scientific principles, not least the Pythagorean teaching that beauty is the result of perfect number ratios.

The neck of the violin is normally made from maple, with an ebony fingerboard. Ebony is used for its hardness and resistance to wear. The neck ends in a peg box and a carved scroll, the fineness of which is often used as an indication of the skill of the violin maker.

This storyboard by Chicago violin shop Fritz Reuter, shows a simple step-by-step illustration of the violin making process.

Why Choose the Violin?

In his book Life Class, Yehudi Menuhin describes the affinity some people have for the violin, explaining that it is not only a melodic instrument, it is also immediately tactile and accessible, even to a child. The violin can be purchased in many different sizes suitable for even the smallest child. These small violins, which can be as tiny as 1/62nd of a full size instrument, are not finely made as they are designed to be resilient for beginners to use, but can be picked up, as Menuhin describes, as easily as a child picks up a teddy bear.

“A child who has a direct natural inclination for the violin has something of an advantage in choosing this instrument over others,” he says. “It is rather like the voice, is a much more tactile instrument than many others and can come in a variety of sizes.

This picture from thesoundpost.co.uk shows the common sizes of beginner instruments for children of different ages.

Menuhin ascribes the appeal of the violin mainly to its sound, which is like that of the human voice.

“With the violin you have to make your own sound and pitch. It is your own voice you are projecting or …learning to project.” He explains that this is why it is possible to distinguish the sounds, tone and styles of different violinists. Playing the violin involves the whole body and this gives the violin the greatest and most immediate range of expression of any instrument.

This playfulness and expression can be seen in this video of a young Sarah Chang playing Sarasate’s Carmen Fantasy.

“I look to the child who, with the child’s confidence, is willing to take up the fiddle, to play it and to play with it, to explore its infinite range of tones and qualities until he finds that voice which is uniquely his own.” Yehudi Menuhin

How the Violin Makes Sound

The body of the violin is a hollow space that functions as an amplifier for vibration. The strings are suspended above the body by a bridge, a small piece of maple wood, which stands on the belly of the violin between the F holes and which is secured to the belly by the tension of the strings. The vibration from the stings is transferred through the bridge to the body of the instrument via the internal sound post. Vibrations are amplified as they meet the hard wood at the back of the instrument and come out through the soft front body and the F holes.

The F holes serve to connect the air on the inside of the instrument to the air outside. As a result of their length and shape, they allow the part of the belly between the holes to move more easily and to vibrate more freely than the other parts of the instrument.

The sound-post, the small upright piece of wood inside the violin, prevents the belly from collapsing under the tension of the strings and couples the vibrations between the stiffer back plate and the bridge. The position of the sound-post is critical to the sound of the instrument. The bass-bar sits inside the belly on the bass-foot side of the bridge, the side under the G-string or bass end of the instrument. This extends beyond the length of the F holes and transmits the motion of the bridge over a large area of the belly.

The air inside the instrument vibrates, exactly like the air in a bottle vibrates when you blow across the top of it.

The violin does not work like an electric amplifier. An electric amp takes a signal with a small amount of power and uses electricity to turn it into a more powerful signal. On the violin, the sound produced by the body of the instrument is created entirely with energy put into the string from the bow. The body of the violin is designed to make the conversion process of vibration to sound optimally efficient. A string on its own makes little sound.

Vibration of the violin strings can be achieved by plucking the strings, which is called pizzicato, or by drawing a bow across them, which is called arco. There are several other ways of making sound, known as extended techniques, which include col legno playing -hitting the string with the wood of the bow- or even tapping on the body of the instrument to make percussive noises.

The bow is strung with horsehair, normally about 150 to 200 hairs from a horse’s tail. Rosin, tree resin mixed with wax, is applied to the hair to increase friction. The surface of the hair shaft looks a little like the tiles on a roof, and the rosin adheres to the raised areas on the surface. Without rosin the hair is too smooth and will slide over the string with virtually no sound.

As the bow is drawn across the string, the air molecules in and around the violin move backwards and forwards, varying the air pressure by tiny amounts. The number of oscillations or vibrations of air pressure per second is called the frequency and is measured in cycles called Hertz (Hz). The pitch of a note is determined by the frequency, for example, 440 Hz, or 440 vibrations per second is the note A in the treble clef, the pitch of the A string. 220 Hz is exactly one octave lower, the A played with the first finger on the G-string.

The pitch of the vibrating string also depends on its thickness. A thicker string will sound lower than a thin one. The tension of the string also determines pitch: the higher the tension, the higher the note. Another differentiation is the length of the string that is free to vibrate. As fingers are added to the string on the fingerboard, the pitch of the note gets higher as the string is effectively shortened. Harmonics produce another mode of vibration, in which the sound waves produced by the string are a fraction of the length of those normally produced.

Here Mark Wood demonstrates the physics of sound on his seven string electric fiddle. This is an extreme example of how the pitch works across the instrument, but it is also clear that the resonance created with electrical signals is very different to that of an acoustic violin with all its nuances of shape.

Tone Production with the Bow

The three main points of violin technique that have an impact on the sound are the weight, speed and point of contact with the bow. The bow must always be drawn at a right angle to the bridge, in a straight line between bridge and fingerboard. Simon Fischer describes this constant point of contact like the needle of a record player in the groove of a vinyl record.

Once the bow technique is developed to allow the flexible, spring-like action in the right arm and bow, the three aspects of tone production and nuance can be explored.

Speed of Bow

The faster the bow stroke, the greater the energy that is transmitted to the violin. If bow pressure remains constant, a change in speed will produce an increase in volume. Decreasing the speed will mean the sound gets quieter. For a musical phrase that requires a constant dynamic, therefore, an equal bow speed should be maintained throughout. A frequent mistake is to use too much bow at the beginning of the stroke and run out towards the end.

Pressure

The pressure of the bow on the strings comes from the weight of the bow itself, the weight of the arm and hand, controlled muscular action, or a combination of the these factors. The bow is heaviest at the frog and therefore whenever an even dynamic is required the pressure must be stronger towards the point. The amount of pressure helps determine the volume of the sound, but the quality of pressure is also important. Too much pressure crushes the string and actually prevents it from vibrating, and can even result in a change of note if the string is pulled too hard. The weight of the hand and arm and the pressure from the muscles must be transferred with freedom of movement and without tension. For example, a rigid right shoulder detracts from the ability to properly use the weight of the arm to apply pressure to the string.

Watch this tutorial by Yehudi Menuhin in which he demonstrates a series of exercises for developing a fluent, flexible right hand:

Sounding Point

The third factor in tone production is the sounding point or point of contact. This is the point in relation to the bridge where the bow has contact with the strings. The optimal sounding point changes in relation to the varying speeds and pressures of the bow, and to the length and thickness of the string. On thinner strings the sounding point is nearer to the bridge than on thicker strings; in higher positions it is closer to the bridge than in lower positions.

Tartini Tones

A further acoustic phenomenon, which Giuseppe Tartini used in his compositions to great effect, also has an impact on tone production. When thirds or sixths are played on the violin, especially on the A and E strings, a third note sounds well below the pitch of the two written notes. These resultant tones, also known as Tartini tones, exist when any two notes are played simultaneously. The pitch of the third tone should be consonant with the double stop. By awareness of these tones, intonation and resonance reach a new level.

Here is Tartini’s Devil’s Trill Sonata. Listen the depth of tone in the double stops.

The sound of the violin is as close as any instrument to the human voice. The ideal for the violinist is that the instrument is almost an extension of the body; it is the violinist’s voice. In order to create this sense, the violinist must learn to use the body without the interference of mental blocks and physical tensions. Mind and body are engaged in practice, and every practice is an opportunity to learn and relearn and to build a healthy relationship between the body and the violin.

The sound of the violin is as close as any instrument to the human voice. The ideal for the violinist is that the instrument is almost an extension of the body; it is the violinist’s voice. In order to create this sense, the violinist must learn to use the body without the interference of mental blocks and physical tensions. Mind and body are engaged in practice, and every practice is an opportunity to learn and relearn and to build a healthy relationship between the body and the violin.

Most focus in practice tends to be on performance. Often the means by which performance is achieved are ignored or taken for granted until injury or pain impedes progress.

Since the sound on the violin is created with the whole body, and the whole body is engaged in the techniques needed to express the music, it is worth spending some time paying attention to the body.

When we practice, all conscious learning takes place within the working memory. This is a limited resource. Nothing can be learned properly if there are too many points of focus at once. Teaching the body to recognise correct postures stretches the working memory and it is not possible to fully focus on the music until the body is comfortable and balanced.

A coordinated body is fundamental for all musical skill and technique to develop.

In his book Life Class, Yehudi Menuhin explains, “My main principle in playing is all-embracing and straightforward: a striving for equilibrium. Perfect equilibrium is, of course, an unattainable ideal, a complex and infinitely multifaceted thing. None the less, one can approach something like right equilibrium when one realises that no part of the body moves without some corresponding reaction or compensation in some other part, in the same sense that not a leaf falls without altering the equilibrium of the earth.”

The engagement with the body therefore becomes an awakening of awareness as to the subtle shifting and balance, the release of tension and the development of mindfulness, which will deepen musicianship, connection and expression in performance.

The subject of how to use the body in violin playing is huge, and different approaches suit different people. Some students find the Alexander Technique helpful, some focus on general wellbeing. There are as many approaches as there are violinists.

Let’s look some of the first points to think about.

- Basic Posture -

Often when playing the violin it’s easy to focus on the upper body but the root of a balanced alignment comes from the feet, legs and pelvis, and from good breathing.

Good posture is about more than standing up straight. Babies instinctively know how to balance as they learn to sit, crawl, stand and walk, but as we get older we often lose this ability and fall into inefficient postures, which we then bring to our violin playing.

The pelvis is integral to correct posture, as it is directly connected to the legs through the hip joints, and connected via muscles to the arms and shoulders. If you think of the pelvis as being the body’s centre of gravity, its positioning becomes vital to good posture whether sitting or standing to play. It should not be either tilted forward or back.

To help achieve balance in the pelvis, the feet should be placed directly under the thigh sockets with toes facing more or less forwards. The knees should be relaxed and in line with the thigh and ankle joints. Then the pelvis rests on the top of the thighs and the trunk is balanced, the chest floats upwards, the rib cage hangs down towards the pelvis and the shoulder girdle rests on top of the rib cage. Think of the head not as a separate entity, as we are encouraged to do with the idea of disparity between mind and body. Instead, include the head as part of the body in your thinking. Your mind is not confined in the space within your skull any more than your body stops at your neck.

To find a good sitting posture, sit balancing upright on your sit bones. You can feel them when you shift your weight from side to side. Think of these sit bones as ‘feet’ that support your torso. Once you have found this solid base, let the spine lengthen up naturally. The knees should be lower than the hips, so if you need to adjust your chair, do so. You can buy blocks to raise the back of chairs which slope backwards, or a wedge cushion to help with posture.

Once you are happy that your posture is comfortable and balanced, bring the instrument to the body, rather than compensating with the body and moving to meet the instrument.

- Positioning the Head -

The head represents about 10% of the body weight. When the neck is not positioned correctly to support the head, the shoulders take the strain. This tension is transferred to the elbows, wrists and hands.

Make sure you have the best shoulder rest and chin rest combination for your body to eliminate unnecessary tension in the neck.

Notice too what is happening with your eyes. Are you under or over focussing, or are you straining your eyes to read the music? Relax the muscles around your eyes and forehead and you will notice a corresponding release of tension in the neck muscles.

Hunching the neck and shoulders is a common habit, and it’s easy to press too hard with the head on the chinrest. Experiment with gripping the violin between the shoulder and chin and notice how the less freedom you have in your head and neck, the more negative emotions may surface. Stiffening the neck stiffens all of the joints of the body.

Hunching the shoulders also limits the movement in the collarbones and shoulder blades, which should float freely from the shoulder girdle. It results in the ribs lifting which gives the heart and lungs less space to work.

See here how the shoulder muscles are attached to the ribs, the collarbone and the arms, and travel right down the body to the pelvis.

Each part of the body moves best when it moves in harmony with the other bones, muscles and limbs. Menuhin describes the process of learning to play the violin as one whereby, “the body of the player becomes aware of itself.” He says, “The principle is grasped not intellectually, but through sensations, through becoming aware of the subtle checks and balances which, when properly understood, permit ease of technique.”

- The Arms -

In playing the violin, the arms function both as a system of levers and as a channel for visceral energy. They carry a charge of energy and emotions from the player to the instrument. For musical expression to be free this route from the torso to the fingers must be without unnecessary tension and the posture must allow energy to flow.

Tension in the neck and shoulders can put pressure on the nerves that lead into the hand, creating pain, pins and needles, numbness and even loss of facility in the fingers.

See from this picture of the human skeleton how the arms and shoulders balance on the body in a free, open way. Try to imagine this space in your own shoulder girdle and feel your spine lengthening as your head floats upwards from your pelvis.

It is also worth observing the range of movement in your wrists. The body works best in the middle of its range of movement. When your wrist is bent forward or backward it is extended beyond this optimal point and this causes tension. This is why a flat left wrist, which leans against the neck of the violin, is not good technique. The hand and wrist are locked in an extended part of the wrist’s range of movement, and this impedes intonation, shifting and vibrato.

- Exercise -

Physical exercise is an important tool in maintaining and developing a healthy body, which in turn has a positive impact on violin practice.

A practice such as yoga is helpful in diminishing anxiety and improving strength and flexibility, and will also teach awareness and knowledge of the muscles.

Yoga based exercises must be approached gently and by no means forced. Find a good teacher. There are a lot of classes run by inexperienced teachers and musicians report suffering two months of tennis elbow, pulled muscles and other disasters after attending classes where the teacher pushes them too fast.

Exercising the body in the right way keeps it supple and adaptable, just as exercising the mind strengthens character and musicianship.

Warm up the body before you practice. A useful selection of stretches is available from the British Performing Arts Medicine Trust. Integrate them to your daily routine.

- Breathing -

Posture is dynamic, not static. Subtle movements such as breathing constantly occur, even when we are still.

Noticing your breathing is also the first practice of mindfulness meditation, which begins to incorporate mind and body in a holistic way. It is not possible to practice the violin without working on the body, and it is not possible to engage the body without using the mind. The violin practice in itself then becomes a holistic and far reaching experience.

Begin where you are today, and begin noticing how you use your body to create your sound on the violin.

Watch other violinists to see how they use the whole body to play and express the music. Here is Joshua Bell playing from his feet:

Make time in your practice to develop this physical learning with a sense of childlike exploration.