The circle of fifths is a musical theory tool that has its roots firmly in mathematics. It explores the relationships between those musical intervals that are most pleasing to the ear, based on discoveries made by the mathematician Pythagoras two and a half thousand years ago.

Pythagoras discovered and investigated the most basic facts about frequency and pitch. He found that there were mathematical ratios between notes. The octave, which is the most basic interval, the point at which pitches seem to duplicate, has a natural 2:1 ratio. If a string of a certain length is set in vibration it will produce a particular note. The shorter the string is, the more times it will vibrate per second, once it is set in vibration. When a string vibrates more times per second, the pitch of the note produced is higher. Therefore, if the string is kept at the same tension but its length is halved, it will produce a note one octave higher than the first. The same happens when you blow through a tube of air. A tube twice the length will produce a note an octave lower.

The circle of fifths, sometimes called the Pythagorean circle, is a diagram with twelve points that represent the twelve semitones within an octave. It is a chart rather like a clock face that organises all the keys into a system and can be used to relate them to one another. It is called a circle of fifths because each step of the circle is a perfect fifth from the next. The fifth is the interval that is closest in character to the octave, in that it is more consonant (less dissonant) or stable than any interval except the octave (or the unison).

A perfect interval is one where natural overtones occur. If you play a note on your violin and listen closely, you will hear the pitch you are playing. You will also hear overtones sounding. The most significant of these, or the easiest to hear, is usually the fifth. Where the ratio of frequencies between octaves is 2:1, the ratio of the frequencies of the fundamental to the fifth is 2:3. A perfect fifth is an interval of seven semitones. These seven semitones represent the building blocks from the first note of a scale to the fifth.

Watch this video for a clear description of how the circle of fifths is built.

The circle of fifths is useful because it shows the relationship between the keys, key signatures and chords.

It can be used to:

Now you’ve watched the video on how to make a circle of fifths, have a look at this interactive circle of fifths. You can use it to look at the relationships between chords in any key.

So what is the circle of fifths useful for?

It is possible to learn the order of sharps and flats as they occur in music by using the circle of fifths. You can work out how many sharps or flats are in a key, and also which notes are sharpened or flattened.

If you look clockwise around the circle you will see the order in which the sharps appear in the key signature. When there is one sharp, it is F#. When there are two, they are F# and C#. Three sharps will be F#, C# and G# and so on.

Looking round the circle in an anticlockwise direction shows the order of flats. If there is one flat it is Bb. Two flats are Bb and Eb. Three are always Bb, Eb and Ab, and so on.

In a circle of fifths in the major keys, C major appears at the top of the circle. C major has no sharps or flats. The next key in a clockwise direction is G major. G major has one sharp, which we now know is F#. Then comes D major which has F# and C#. Going in the other direction, F major has one flat, Bb. Bb major has two flats, Eb major has three flats.

Use the interactive circle of fifths above to notice the enharmonic changes this creates in flat keys between, for example F# and Gb. Look at the circle in D major and then in Db major to see how the pitches are renamed. Two notes that have the same pitch but are represented by different letter names and accidentals are described as enharmonic.

The circle of fifths can also be used to work out which keys are related to each other. You can see that the keys on either side of C are F and G. Therefore, the two closest keys to C, which has no sharps or flats, are F, which has one flat, and G, which has one sharp. F and G therefore make up the primary chords in C major. F is chord IV, the subdominant, and G is chord V, the dominant. Using these three chords you can build the standard chord progression IV V I.

The secondary chords are those further away from the note of your key, so in C major, D, A and E would be secondary chords, which means they may appear in the harmony of your piece but are not as strong as the primary chords.

Watch these two clips. They explain how the circle of fifths works in major and minor keys:

The circle of fifths is also useful for understanding chord progressions such as those from dominant seventh chords. Dominant seventh chords have a tendency to want to go towards another chord. They contain a dissonance that melodically and harmonically needs to resolve. The chord that the dominant seventh resolves to is one fifth lower, so A7 resolves to D major, F7 resolves to Bb major, and so on. If you are asked to play a dominant seventh in the key of D, you will start on the note A.

Here is another clip explaining how to use the circle of fifths to understand your scales.

The model of a circle of fifths, with the consequent understanding of chord progressions and harmony and the hierarchy and relationships between keys, has played a hugely important part in Western music.

When you first start learning the violin, you will also start learning to read music.

To a musician, written music is like an actor’s script. It tells you what to play, when to play it and how to play it.

Music, like language, is written with symbols which represent sounds; from the most basic notation which shows the pitch, duration and timing of each note, to more detailed and subtle instructions showing expression, tone quality or timbre, and sometimes even special effects.

What you see on the page is a sort of drawing of what you will hear.

The notes in Western music are given the names of the first seven letters of the alphabet: A, B, C, D, E, F and G. Once you get to G the note names begin again at A.

The notes of the violin strings without any fingers pressed down, which are commonly known as the open strings, are called G, D, A and E, with G being the lowest, fattest string and E the highest sounding, finest string.

When notated, the open string sounds of the violin look like this:

You will see that the notes are placed in various positions on five parallel lines called a stave. Every line and space on the stave represents a different pitch, the higher the note, the higher the pitch.

The note on the left here is the G - string note, which is the lowest note on the violin. The note on the right is the E - string pitch, which is much higher.

The round part, or head of the note shows the pitch by its placing on the stave. Each note also has a stem that can go either up or down.

The symbol at the front of the stave is called a treble clef. The clef defines which pitches will be played and shows if it’s a low or high instrument.

Violin music is always written in treble clef. When notes fall outside of the pitches that fit onto the stave, small lines called ledger lines are added above or below to place the notes, as you can see with the low G - string pitch which sits below two ledger lines.

Once too many ledger lines are needed and the music becomes visually confusing, it’s time to switch to a new clef, such as bass clef.

The numbers after the treble clef are called the time signature. The stave works both up and down (pitch) and from left to right.

From left to right, the stave shows the beat and the rhythm. The beat is the heartbeat or pulse of the music. It doesn’t change.

The music is written in small sections called bars, which fall between the vertical lines on the stave called bar lines.

Some pieces have four beats in a bar, which means you feel them in four time, some have three, like a waltz, and so on.

The time signature shows how many beats are in each bar, and what kind of note each of those beats is.

The rhythm is where notes have different durations within the structure of the bar. This is where pieces can really start to get interesting.

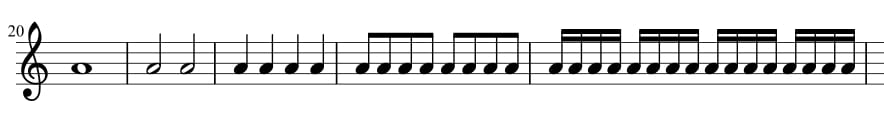

Here we can see a variety of rhythms.

Each of these bars has a value of four beats. The first of the notes above is called a semibreve. It lasts for four beats.

Each of these bars has a value of four beats. The first of the notes above is called a semibreve. It lasts for four beats.

The second is called a minim (or half note, in America) and each minim lasts for two beats. You can see there are two minims in a four-beat bar.

The third example is a crotchet or quarter note. Each crotchet is one beat long.

The fourth rhythm is a quaver, or eighth note, which lasts for half a beat, and the last note value shown is called a semiquaver or sixteenth note, and lasts for quarter of a beat, so sixteen semiquavers fit into a four beat bar.

The smaller notes are written in groups of four so they match up with the beat visually and are easy to read. Each note length has a corresponding symbol to show when there is a rest (silence) of that duration.

The time signature 4/4 shows that there are four beats in each bar (the top 4) and that each of those is a crotchet or quarter note (the lower 4).

The time signature 3/8 would show three (the top number) quaver, or eighth note, (the bottom number) beats in a bar.

As you put your fingers on the strings to play new notes on the violin, the music shows the pitch rising. So the first finger note on each string of the violin would look like this: The note after G on the G – string is called A and is played with the first finger.

The note after G on the G – string is called A and is played with the first finger.

The note after D on the D – string is called E, on the A – string it’s B and on the E – string it’s F.

The first finger in violin fingering is the index finger, unlike on the piano where 1 denotes the thumb.

There are other symbols which show pitch, one of which, the thing that looks like a hash tag, is shown above. This one is called a sharp and the full name of the second note shown on the E – string is F sharp.

You will see these symbols for sharps or flats in the key signature of nearly every piece. The key signature is placed between the treble clef and the time signature and shows you which key or tonality to play in.

As you add the other fingers, you can see below how the gaps on the stave are filled, until you are playing every first position note on your violin. As you build up your fingers one at a time, the pitches on the stave look like this:

The very last note here is played with the fourth finger on the E – string.

It is worth noting at this point that because the pitches of the violin strings are five notes or a fifth apart, each open string note after G can also be played with the fourth finger or pinkie on the previous string, so the A – string note, for example, can be played with the fourth finger on the D –string.

This seems a lot to remember but there are a couple of helpful memory tricks:

The notes in the spaces of the stave, in ascending order, are F, A, C and E, or FACE.

The notes on the lines are E, G, B, D and F. You may remember learning the mnemonic, Every Good Boy Deserves Fun.

You will soon begin to memorise which note corresponds to which sound and finger placement on your violin. Remember that when you learned to read, you were simultaneously studying writing skills.

Try downloading and printing this music manuscript paper, and practice writing out the notes as you learn to play them. Write out the open string notes and practice from your own copy.

Making the connection between writing, reading and playing will speed up and deepen the process of learning.

Soon the note reading will become habitual, and just as you don’t have to process every letter to read a word, you will begin to see the piece as a whole rather than having to read each note and work out where to play it.

As with any new skill, the more you practise and try it out, the more confident you will feel and the sooner you will be reading music fluently.

The articulation of sounds on the violin is much like the production of different consonants and vowels in speech, and the nuance in expression of tone. The many ways of articulating notes with the bow makes them speak in different ways.

Articulation in violin music is created using range of bowing gestures. These can give the violin an array of different sounds on any one pitch. These differences are mainly in the transient sounds at the beginning and end of the note, and in the length of the note and the attack of the bow. Various techniques of bow pressure, position of the bow (point of contact), angle of the bow and position and movement of the wrist, fingers and elbow are used to create different shapes in with the sound.

These techniques can be described as bowing patterns, or thought of in terms of tone qualities, speed, pressure and position of the bow.

The first articulations the violinist will encounter are the simple ideas of separate bows and legato. In separate bows, the direction of the bow is changed for each note, so each note occurs up bow, down bow, up bow, down bow and so on. In legato bowing, two or more notes are played in one bow stroke. Sometimes separately articulated notes are played within one bow stroke.

Legato bowing creates two main challenges. Firstly, the sound of the bow must not be disturbed by what the left hand is doing. An exercise such as the first study in the Schradieck School of Violin Technique is helpful for coordination of the left hand within a slur. This can be more complicated when a fingering during a slur involves a substantial change of position. A change of position not only requires a change in sounding point, the violinist will have to use the bow to help the left hand make the shift. By slowing down the bow stroke slightly and lifting the pressure whilst the left hand is shifting, a shift can be camouflaged without disrupting the legato flow.

The second challenge of legato bowing is where the slur involves any string crossing. A slight pressure of the bow as the string crossing is made will help bind the tone of the first and second note. Generally, the best technique for smooth string crossings within legato is to approach the second string gradually, so as the first note is slurred to the second, a double stop will sound momentarily. This double stop happens so subtly it is not possible to distinguish it, and only the desired note, aided by the slight bow pressure, is heard.

Where the bow changes back and forth between two strings several times in one bow stroke, it is easiest to keep the bow as close as possible to both strings at once whilst still making sure each note sounds clearly. String crossings like this are hardest at the heel of the bow because they require a subtle and active use of the right hand fingers. Practice studies for legato string crossings can be found in Exercise IV of the Schradieck tutor.

Détaché bowing can, in its simplest form, be described as playing with separate bows. However, the more advanced détaché stroke has a slight swelling at the beginning of the note, followed by a gradual lightening. This is created by adding a slight pressure at the beginning of the note without accenting it. When the stroke is played continuously the infection gives the impression of separation between the notes.

Portato bowing is very similar to détaché bowing and performed using almost the same technique. However, portato is a series of détaché strokes played with one bow stroke. This articulation is used to bring more expression to slurred legato notes.

There are many more advanced and subtle bow techniques, all of which create different articulation in the sound of the violin. Some of the more unusual and distinctive include:

Other more advanced bowing techniques can be learned to produce a huge variety of articulation, character and sound.

The Forty Variations opus 3 by Otakar Ševčík is a compact introduction to many bow strokes including collé and spiccato. Collé is a very important practice bowing, invaluable for developing control of the bow in all its parts. It is also musically useful, being incisive and short.

Spiccato is a bow stroke in which the bow is dropped from the air above the string and leaves the string again after each note. It is played mainly in the lower two thirds of the bow and can range from very short to fairly broad.

Articulation markings in music are indicated by various dots, lines and shapes attached to the note. Generally, a note with a dot above or below is played short, and one with a line is played long. These markings inform which gesture the violinist will make with the bow. A passage of quavers, for example, all articulated with dots, might be played with a spiccato bow stroke. The symbol > above or below a note indicates that the note is played with an accent.

A list of common articulation markings can be found here.

The extent of articulation and nuance possible with advanced study of bowing techniques is as broad as the range of language and expression of a skilled singer. This exploration of some of the basic concepts is only an introduction to the possibilities of violin articulation. Ask your teacher to show you some of the more detailed bowing skills, and use studies and repertoire to develop your vocabulary of sounds.

For more ideas on right hand technique and how the bow arm produces sound, read the ViolinSchool article on Tone Production.

Listening is one of the most important skills you can have. How well you listen has a major impact on your effectiveness at work, your relationships and your musical practice.

Listening enables you to learn, to obtain information, to understand and to enjoy, yet it can often feel like an abstract ability. Research suggests that most people remember only 25 to 50 percent of what they hear, meaning that whether you’re talking to a friend, listening to your violin teacher or listening to your violin practice, you’re paying attention to at most, half of what’s going on.

By becoming a better listener, paying attention to how you listen and what you are listening for, violin practice will improve, but good listening and its application in violin practice requires a high level of self-awareness, attention, positive attitude, flow concentration and critical thinking skills.

Listening in violin playing comes in many different guises:

First, prepare yourself to listen. Put other things out of your mind. If you notice you are thinking about what you’re going to have for dinner, allow the mind to re-focus on the music you are about to play, the sound you want to make and the shape of the musical phrase you would like to express. It is very easy to allow the brain to drift into autopilot.

Warm up by playing some long notes and slow scales. Really engage with the sound you are producing. Try to do so non-judgementally, just enjoying the variations of vibration and tone. As your body warms up, give yourself some images of colour, texture or objects, for example, a smooth piece of dark blue velvet. Visualise the feeling and the colour, and then play some notes with the same feeling. Really listen to your tone and the feelings you produce from the notes.

Practice focussed concentration. Break your violin practice into short bursts so you can really listen. The mental state in which you are fully immersed in what you are doing, known as flow or being in the zone, represents the deepest levels of performing and learning. In flow, the emotions are positive, energised and aligned with the task in hand. This level of positive focus is most likely to occur when you are practising with purpose; with a clear set of goals and progress, giving direction and structure to the practice, and with clear feedback; so having actually really listened to what you’ve just played.

It is important to find a balance between the perceived challenges of the music or technique you are practising, and your level of skill as you perceive it: You must feel confident in your ability to achieve what you want.

Broken down, this level of concentration can be achieved when you know:

If you are bored or anxious, it is very difficult to concentrate properly, and to listen to what you are really playing without negative preconceptions. Use visualisation, listen in your mind to what you want to do, listen to the results and enjoy the process. This is where your critical thinking skills will come in. Use the information gathered from listening fully to what you are doing to evaluate what you are doing and how you might develop it.

Full concentration, really listening to what you are doing, is more likely to produce the information and results you want than simply hearing what you’re playing.

Try breaking down what you hear into separate parts so you can listen more closely. Work on the rhythm, intonation, tone, phrasing and other musical ideas individually, and then start to put everything back together. Sometimes when you concentrate on the rhythm, the tuning will go funny, for example. Don’t worry about this; your brain is focussed on integrating your understanding of the rhythm. You can go back to the intonation later.

Allow your ears to listen to the sound in the whole room, not just to the sound coming from your violin. Imagine you have one ear at each side of the room. Sometimes it can be interesting to put an earplug in your left ear to hear the sound that is going into the space rather than the noise under your earhole!

Read the article about visualisation skills for more ideas and practice techniques.

You can use the ViolinSchool Auralia ear training software (included free with your ViolinSchool membership) to practice your listening skills and deepen your understanding of the music you are learning. Most music has three main ideas to notice: new melodies, repetition and variation. You can also look for colour, balance and texture, key (major or minor), rhythms and accompaniment. The more you understand about how your piece is put together, the easier it is to feel confident in how you want it to sound.

Listening to someone you admire playing the piece you are learning is one of the best ways to motivate yourself and understand the music. You can develop a mental map of the characters, colours and energies that make up your piece.

Listen to the piece as a whole and in small sections. It can be fun to listen to a phrase and then try to recreate the sounds and shapes you heard on the recording. Many beginner violin books and graded exam books now come with CDs. For children learning the Suzuki method, listening is one of the first skills learned. Suzuki encouraged his young students to listen to recordings of great violinists, and his method is based on the mother tongue ideal of repetition and imitation. Suzuki children normally start off playing the violin with a beautiful tone because they have listened so much to the sound of the violin. Ultimately, listening to the piece before and during study allows you to build a concept and an ideal of the music, and motivates your listening and your practice.

Recording your violin practice and performances and listening back is an extremely useful practice tool. Don’t listen back immediately if you feel it might be a negative experience. Record one day and listen back the next so you have a little distance from the process of “doing”. Often you will pick up on all sorts of things you missed. The violin is right under the ear and it can be difficult when you’re actually playing to pick up on things that are obvious when you are focussed solely on listening.

It can be easy to go into a lesson with a preconceived idea of what you can and cannot do. Your teacher will have a completely fresh perspective on what you are playing and will hear positive things and aspects you can work on, some of which you may think didn’t sound so good, or which you hadn’t noticed weren’t working. When your teacher is explaining something, don’t talk. Listen. Don’t interrupt or talk over them or you will miss vital information. You already know what you think; this is the time to take advice.

Listen to feedback in a positive way. Feedback that tells you why something isn’t working and how you can make it better is incredibly valuable; don’t let it depress you if your teacher isn’t constantly complimentary. Listen to the feedback and add it to your information banks. It would be much worse if nobody in your support network ever told you something didn’t work and it was only picked up in an important concert.

Playing with other people requires a whole new level of listening. Suddenly you aren’t just listening to your own sound, tuning and rhythm, you’re listening to the group sound and required to play in time and in tune with other people.

Have a look at the article about Ensemble Playing for some in depth ideas for playing with other musicians.

The whole point of playing the violin is to enjoy its sound. Without listening, there is no function to the music. Developing the conscious listening skills in practice that enable you to really express the music in performance is a really important part of practice and learning. Learning to listen when you practice, and to hear the elements of music as it’s performed, will heighten your enjoyment when you go to a concert, or when you hear birdsong, the wind in the chimney or the waves on the beach. You might even find you are listening and communicating better with others.

Start noticing your listening when you practice and see what else comes into your awareness through practising this essential skill.

Sight Reading for Violin

“The ability to sight-read fluently is a most important part of your training as a violinist, whether you intend to play professionally or simply for enjoyment. Yet the study of sight-reading is often badly neglected by young players and is frequently regarded as no more than an unpleasant sideline. If you become a good sight-reader you will be able to learn pieces more quickly and play in ensembles and orchestras with confidence and assurance.” Paul Harris, author of the Improve your sight-reading series.

Sight-reading is a really important skill. We sight-read new pieces in orchestra and duet rehearsals, we get sight-reading tests in exams and auditions; if you can’t sight-read, learning a new piece, or even choosing which piece to learn, is an arduous task. An ability to sight-read well opens up opportunities to enjoy ensemble playing and take charge of your own learning. Good sight-readers are more versatile performers because they are able to assimilate new music and diverse styles very quickly, and to perform with minimal rehearsal time. Learning to sight-read well should be at the top of every violinist’s list of priorities.

The main problem with sight-reading is that we start to see it as separate from our other musical skills and even our basic musicianship. Faced with a piece of sight-reading, we shut down our brain to all of the things we have learned and enjoy about the instrument, and panic.

Fundamentally, sight-reading is the skill of reading music, and how that reading transfers into movement and sound. Sight-reading is a skill, and it is true that the more you do it, the more fluent you will become, but there is no point spending hours trying to improve unless you understand the elements of the skill. It is essentially a mental activity, the message travelling from eyes to brain to fingers, and it is important not to try too hard or you’ll get in your own way! Really successful sight-reading is relaxed, calm and musical.

It is important to practice sight-reading regularly as part of your practice. Once you have grasped the basic concepts, the skill needs constant reinforcement to instil good habits. If you can’t bear to practice on your own every day, arrange to meet friends for ensemble playing and read through new pieces with them.

Only accessible material enables you to acquire the habits that will lead to fluency. Don’t choose to sight-read complex material, start with really basic music and build up to more complicated pieces gradually. Get as many sight-reading books as you can so you don’t run out of material. Paul Harris’s graded series, Improve Your Sight-reading is excellent, because it starts by breaking down the basic components of pulse, rhythm and melody, and the exam boards have books of specimen tests available. You could even use the pieces or sections of pieces you don’t know in any book you are working from. As a rough guide, it’s an idea to start learning to sight-read using music which is much easier than your current repertoire.

Practice sight-reading slowly; learn the positions of the notes on the stave and how they relate to your left hand finger patterns. Scales are great for learning finger placement. Make sure you know some basic theory concepts such as key and time signatures. Don’t be fazed if you come across something you’ve not seen before. That happens to everyone. Just find out what it is.

The first thing to do when faced with a piece of music you haven’t seen before, because that’s all sight-reading is, is to prepare the piece.

As you become more experienced, this process will speed up and you will be able to gauge most of the information you need by visually scanning the music before you start.

Successful sight-reading is largely a matter of good quality concentration. Your mindset and focus as you look at the page is the most important factor. Notice your eyes. Visual steadiness is crucial. Relax your eyes and don’t let them fidget and flit about, losing connection with what you are doing. Instead of going through the motions of reading, really focus. True concentration is difficult to maintain for long, but you don’t have to work hard, merely practice awareness. The second you notice your concentration has gone, you have already refocused yourself.

Problems generally arise when we are not ready for the notes as they arrive. Your eyes are looking at a note and you are also playing that note, and sometimes it’s happening so fast that your brain can’t process the information. Then you start to feel that blind panic which makes you hate sight-reading. The trick is to continually read ahead. Keep your eyes moving a few beats in front of where you are playing. Sight-reading in this respect is actually the process of visually memorising short snippets of music you are about to play whilst playing something else. This allows the fingers to be ready for the notes as they arrive, and suddenly you are playing fluently.

Reading ahead enables you to look at the music in bigger chunks. Instead of looking at each note as a separate event, you start to see how its rhythm fits into the beat, and melodically where scale and arpeggio patterns appear and how other intervals fit in.

Don’t react to mistakes. As soon as you give too much attention to a mistake, your concentration is no longer on what you are doing, and the chances are you are just about to make another mistake, and another. Decide to play all the way through without stopping. Keep going at a steady tempo and don’t worry about a dropped note. Imagine how quickly an orchestra would fall apart if every player who made a mistake hesitated or went back to correct it. Soon nobody would be in the same place at all. Prioritise. If on your first try you are able to keep the pulse but play all of the wrong notes, that’s a good start.

So as you prepare to play the piece remember:

Sight-reading is simply the process of playing a piece of music you haven’t seen before. Don’t separate it from your other musical skills in your mind; approach it with enthusiasm, curiosity and confidence. And now you have the tools to learn how to sight-read, never dismiss sight-reading practice as dull and unnecessary. It is one of the most fundamental skills a violinist needs.

“To rely on muscular habit, which so many of us do in technique, is indeed fatal. A little nervousness, a muscle bewildered and unable to direct itself, and where are you? For technique is truly a matter of the brain.” Fritz Kreizler, violinist and composer 1875 -1962

Visualisation, the process of creating compelling images in the mind, is one of the most valuable tools for learning and integrating skill, building confidence and achieving success, yet we constantly underuse it in our lives and our violin practice.

Visualisation accelerates the learning of any skill by activating the power of the subconscious mind, focussing the brain by programming the reticular activating system - the filter which mediates information and regulates brain states - to seek out and use available resources, and by raising the level of expectation, motivating a better result.

Scientists have found that the same regions of the brain are stimulated when we perform an action and when we visualise performing that action: If you vividly imagine placing your left hand fingers on the fingerboard of your violin, your brain activates in exactly the same way as if you were actually doing it – your brain sees no difference between visualising and doing. This research is used to great effect to help stroke patients reactivate muscles that have lost their facility: It has been found to be possible to build strength in a muscle that is too weak to move by simply repeatedly imagining the movement.

[MM_Member_Decision isMember='false']You will need to register for ViolinSchool membership in order to read the rest of this article! Click here to see all the benefits of becoming a member, and to join today![/MM_Member_Decision][MM_Member_Decision membershipId='1']You currently have a free account! To read the rest of this article, you will need to register for ViolinSchool membership. Click here to see all the benefits of becoming a member, and to join today![/MM_Member_Decision][MM_Member_Decision membershipId='2|3']The process of visualisation, which was initially dismissed by many as unfounded, is described in W Timothy Gallwey’s 1974 book, The Inner Game of Tennis.

“There is a far more natural and effective process for learning and doing almost anything than most of us realize. It is similar to the process we all used, but soon forgot, as we learned to walk and talk. It uses the so-called unconscious mind more than the deliberate "self-conscious" mind, the spinal and midbrain areas of the nervous system more than the cerebral cortex. This process doesn't have to be learned; we already know it. All that is needed is to unlearn those habits which interfere with it and then to just let it happen.

Visualisation simply makes the brain achieve more. Sports psychologists and peak performance experts have been popularising the technique since the 1980s, and it has been integrated into almost all mainstream sports and performance coaching, success programmes and business training.

Athletes using guided imagery and mental rehearsal techniques can enhance their performance by creating mental images to intend the outcome of a race. With mental rehearsal the body and mind become trained to actively perform the skill imagined. Repeated use of visualisation builds experience and confidence under pressure, maximising both the efficiency of training and the effectiveness of practice. This principle applies to learning anything new. According to Jack Canfield, in his 2004 book, The Success Principles, Harvard University researchers found that students who visualised tasks before performing them, performed with nearly 100% accuracy, where those who didn’t use visualisation achieved only 55% accuracy. This is also true when applied to the process of learning the violin, both during practice time and performance.

“Fortune favours the prepared mind.” Louis Pasteur, chemist and microbiologist, 1822 - 1895

Most of us are familiar with the idea of reading ahead in the music, or of hearing a note or pitch before playing it. Visualisation - not only conceiving of a phrase before playing it, but vividly imagining the sound, how it feels, where the fingers will fall, how the hand will move in a certain shift and even how the performance will go - is a much deeper way of mentally absorbing and preparing the information. It is also one of the best ways to rid your practice of monotonous repetition and develop awareness of your musical actions.

It’s all very well knowing how great visualisation can be, but how do you go about it? What happens if you close your eyes and don’t seem to be able to see anything?

There are two different ways of visualising, depending on your brain type, both of which are absolutely legitimate. Some people are what psychologists refer to as eidetic visualisers. When they close their eyes they see things in bright, clear, three-dimensional, colour images. The majority of people, however, are noneidetic visualisers. This means they don’t really see an image as much as think it. THIS WORKS JUST AS WELL!

Before we look at how we can apply visualisation techniques in violin practice, let’s look at an example exercise from The Inner Game of Tennis, in which the aim is to hit a stationary target with a tennis ball:

“Place a tennis-ball can in the backhand corner of one of the service courts. Then figure out how you should swing your racket in order to hit the can. Think about how high to toss the ball, about the proper angle of your racket at impact, the proper weight flow, and so forth. Now aim at the can and attempt to hit it. If you miss, try again. If you hit it, try to repeat whatever you did so that you can hit it again. If you follow this procedure for a few minutes, you will experience what I mean by "trying hard" and making yourself serve. After you have absorbed this experience, move the can to the backhand corner of the other service court for the second half of the experiment. This time stand on the base line, breathe deeply a few times and relax. Look at the can. Then visualize the path of the ball from your racket to the can. See the ball hitting the can right on the label. If you like, shut your eyes and imagine yourself serving, and the ball hitting the can. Do this several times. If in your imagination the ball misses the can, that's all right; repeat the image a few times until the ball hits the target. Now, take no thought of how you should hit the ball. Don't try to hit the target. Ask your body, Self 2, to do whatever is necessary to hit the can, then let it do it. Exercise no control; correct for no imagined bad habits. Having programmed yourself with the desired flight of the ball, simply trust your body to do it. When you toss the ball up, focus your attention on its seams, then let the serve serve itself. The ball will either hit or miss the target. Notice exactly where it lands. You should free yourself from any emotional reaction to success or failure; simply know your goal and take objective interest in the results. Then serve again. If you have missed the can, don't be surprised and don't try to correct for your error. This is most important. Again focus your attention on the can; then let the serve serve itself. If you faithfully do not try to hit the can, and do not attempt to correct for your misses, but put full confidence in your body and its computer, you will soon see that the serve is correcting itself. You will experience that there really is a Self 2 who is acting and learning without being told what to do. Observe this process; observe your body making the changes necessary in order to come nearer and nearer to the can, Of course, Self 1 is very tricky and it is most difficult to keep him from interfering a little, but if you quiet him a bit, you will begin to see Self 2 at work, and you will be as amazed as I have been at what it can do, and how effortlessly.”

You can already see how this same exercise might be applied to practising a particular shift or bow stroke, any specific element of your piece that requires a certain physical movement to gain a result.

Here are some more practice and performance ideas from The Musician’s Way, A Guide to Practice, Performance and Wellness by Gerald Klickstein, 2009

Start using visualisation in your practice. You will find you achieve much better results and increased confidence, you can practice at antisocial hours of the day or night, you can save tired muscles, and you will develop a much deeper, intuitive understanding of the instrument and the music. Visualise, imagine and mentally prepare at least as much as you physically play. As you practice visualising it will become easier to integrate it at speed and under pressure.

Visualisation is counter-intuitive in a culture where we are taught to try, try, try again, but it is without doubt the single most powerful practice technique that most of us don’t use!

“If you cannot visualise what it is you wish to become, then the brain doesn’t have the first clue how to get you there." Chris Murray, Author of The Extremely Successful Salesman’s Club

“When everyone else has finished playing, you should not play any notes you have left over. Please play those on the way home.” Anon.

Making music with other people is one of the best ways to enjoy playing the violin and an important part of developing your skills as a musician. The benefits of playing as part of a group or ensemble include improvement in every aspect of general musicianship, a better sense of pulse, rhythm and intonation, a heightened awareness and a chance to learn from each other’s strengths and weaknesses.

A chamber music ensemble plays without a conductor. This is a small group such as a string trio or quartet with one person playing each part. A larger ensemble where many people are playing the same part, normally guided by a conductor, is called an orchestra.

When you are learning to play in an ensemble of any size, there are important skills you must develop and practicalities to consider.

Say you’re playing your violin in an orchestra for the first time. What things do you need to know?

Chamber music playing is different from orchestral playing. Communication is intensified because there is no conductor. To play one to a part gives more interpretive freedom but means you have to really communicate to form expressive unity. Playing in a small group is more individual and personal than playing in an orchestral section but still requires the musicians to merge their ideas. In some ways, chamber music is a solo activity because you are the only person playing your musical line. It’s also a social activity in which you are making music with friends and have to be perpetually responsive to what they are doing. It doesn’t work unless you are listening and responding to each other, not only when you are playing, but also in the discussions that inevitably arise during rehearsal.

Here are some tips and ideas for playing in a chamber ensemble:

Enjoy the experience of playing with other musicians and discovering great music together. There is nothing better than the exhilaration of creating something that is greater than the sum of its musical parts, and of extending your own technique and creativity along the way. You will learn musicality, diplomacy, how your friends take their tea, and most of all, you will open yourself up to a world of great music.

As Christmas approaches, it is always a nice chance to learn some festive music to get into the seasonal spirit.

There is loads of Christmas music available, from carols to favourite pop songs, but before we delve into the Christmas goodies, here’s some improvised fiddle fun from Peter Lee Johnson to get you in the mood…

If you want to try something less complicated, there is a wealth of music for beginner and intermediate level violinists. Perhaps the best book for adults and children is by Kathy and David Blackwell, authors of the Fiddle Time series. They have put together a great selection in Fiddle Time Christmas (Oxford University Press). It’s available on Amazon, where it has five star customer reviews.

[MM_Member_Decision isMember='false']You will need to register for ViolinSchool membership in order to read the rest of this article! Click here to see all the benefits of becoming a member, and to join today![/MM_Member_Decision][MM_Member_Decision membershipId='1']You currently have a free account! To read the rest of this article, you will need to register for ViolinSchool membership. Click here to see all the benefits of becoming a member, and to join today![/MM_Member_Decision][MM_Member_Decision membershipId='2|3']Their book contains 32 Christmas tunes, some well known favourites and some lesser known songs, many of which have the words to sing along to; there’s a selection of solo and duet pieces and easy chord symbols for piano or guitar accompaniment. The arrangements are nice and easy with simple finger patterns and the book even comes with a CD to listen or play along to.

Let’s take a quick look through the book.

The first song is the Christmas carol Hark the Herald Angels Sing, which is a lovely tune by Mendelssohn. This version is in G major and has simple rhythms. Look out for the C naturals on the A string, which need a low second finger, and try singing the words to help with the dotted rhythms. The dynamics increase as the song draws to a triumphant close.

The first duet piece is the traditional English melody The Holly and the Ivy. This song has three beats in a bar. Most of the rhythms move together between the top and bottom parts, but look out for places where one player has two quavers and the other has a crotchet. Much of the harmony is quite close so listen to make sure your tuning works together.

The same is true of Silent Night, a bit further on in the book. Close harmony needs good intonation so that the song sounds really beautiful. Notice the dynamics in Silent Night. There are ‘hairpins;’ crescendos and diminuendos marked to shape each phrase in the same way that you would sing it. Listen to the way the phrases are sung by these choristers.

The next duet is I Saw Three Ships. This is in a compound time signature, 6/8, which sounds like a jig or sea shanty. This recording gives a strong sense of the dance-like rhythm from an unlikely source.

The book continues with the carol Oh Little Town of Bethlehem, and the Trinidadian carol Christmas Calypso. Again this is a more complicated rhythm. Sing the words and notice where the strong beats fall. The bow distribution is slightly tricky in this song as there are notes of different lengths mixed up in each phrase. Try using slightly less bow for the quavers and more for the crotchets to help divide up the bow and to give the swinging calypso rhythm. Listen to this Christmas Calypso to hear the gentle sway and emphasis of the beat.

The next few songs are Once In Royal David’s City, again in G major, so look out for those C naturals, then Go Tell it on the Mountain and O Christmas Tree. O Christmas Tree is another duet which will be great fun to play with a friend. Playing Christmas songs together is great fun for adults and children. Although the children in this video are playing in D major, their performance gives a great idea of the rhythm of the song.

We Wish You a Merry Christmas, While Shepherds Watched and We Three Kings are next. Many of these songs will be familiar to even young children who will have heard them or sung them at school. It’s always nice to start with the songs you know. Listen to them all on the CD and you’ll discover plenty of new songs too.

Next come plenty more favourite carols including Away in a Manger and God Rest Ye Merry Gentlemen, before the carols are interrupted by a simple version of the famous Skaters’ Waltz by Waldteufel. Listen to the full orchestral version and imagine the skaters gliding over the ice! Waldteufel’s name is pretty fun too. It’s German for Forest Devil.

The next tune is from Tchaikovsky’s Nutcracker ballet, which is a huge Christmas favourite with a surreal surfeit of dancing mice and sweets. Watch these dancers performing Dance of the Reed Pipes. Notice how the shape of the dance follows the shape of the music.

The book ends with some more famous melodies, including Jingle Bells, and two Hogmanay tunes. Hogmanay is Scots for the last day of the year, and the Hogmanay Reel is a Scottish dance tune. Auld Lang Syne is a song traditionally sung on New Year’s Eve and also at the very end of any decent Scottish party when everyone is feeling sentimental about having to go home.

Fiddle Time Christmas is a really great place to start learning Christmas music, but there are also plenty of Christmas songs available as free downloads. There is a nice selection of carols at www.violinonline.com. They all come with sheet music, scores and sound files. Some are perfect for beginners, and others more suitable for the intermediate player. It Came Upon a Midnight Clear has some more advanced accidentals and the Messiah Medley is quite challenging but great if you like Handel’s music.

Fiddlerman.com has a downloadable version of Chestnuts Roasting on an Open Fire, suitable for intermediate players. There’s no sound file and it’s not in the original key because vocal scores are often in very difficult keys, but if you love the song, here it is.

Christmas only comes once a year, so dive into the seasonal repertoire, have fun, and happy Christmas!

[/MM_Member_Decision]

Stage fright is a state of nervousness or fear leading up to and during a performance. It is an exaggerated symptom of anxiety. The hands sweat or become icy cold, the body shakes, sometimes symptoms include nausea, an overwhelming sense of tiredness, a need to go to the toilet or shortness of breath, and there can be a frightening sense of disassociation; of playing your instrument from behind a curtain through which you simply cannot connect with what you’re doing.

Stage fright is a very common problem amongst performing musicians. In one recent survey 96% of the orchestra musicians questioned admitted to anxiety before performances. It’s common to see the backstage sign leading Stage Right enhanced with a cynical ‘F’, and this self-mocking comment is pertinent. To many performers stage fright represents a destructive personal shortcoming.

The physical symptoms are the result of a primal instinct known as Fight or Flight. This is the inborn physiological response to a threatening or dangerous situation. It readies you either to resist the danger forcibly – Fight - or to run away from it – Flight. Hormones including adrenaline flood into the bloodstream, the heart rate, blood pressure and breathing rate all increase, the neck and back muscles contract, which means that if you try to maintain an upright posture your muscles shake violently, the digestive system shuts down.

It’s useful on a basic level to understand what is happening to cause the unpleasant physical symptoms of stage fright. It’s also worth knowing that everybody suffers from it to some degree or at some point in their life, no matter how successful or famous. Even Heifetz who was renowned for his perfect performances was apparently stricken with fear before he went on stage, convinced that two thousand nine hundred and ninety nine of the three thousand audience members had come to hear him play a wrong note.

It is useful to know these things but it is not, in reality, any help at all when you are in the grip of stage fright.

So what is the reason for stage fright?

The danger your body is reacting to is the performance. There’s a fear you won’t do yourself justice. The more important the outcome of the performance, the worse the anxiety will be. If the stakes are high, say you’re auditioning for an orchestra you’ve always wanted to play with, you’re broke and you need the money, you’re playing in a competitive situation where you know your performance is being judged in a critical way, even more adrenaline will release and the resultant anxiety can be paralysing.

Many instrumentalists, particularly those playing an instrument as tactile and personal as the violin, relate very strongly with their instrument. “I am a violinist,” becomes more than a job description. In situations like this, the identity of the self as a musician can seem to rely on the outcome of the performance.

There is also a genetic aspect. Some people are simply more genetically predisposed to strong feelings of anxiety than others.

Another aspect behind performance anxiety is the level of task mastery. The more comfortable you feel with your playing, the more confident you will feel. Our fears of unreliable shifting, stiff left hand, bow shake or dropping the violin are all founded in an unreliable physical reaction.

What has really happened in stage fright is that the positive aspect of music making, an overriding desire to communicate, has somehow become lost as the ego distorts the relevance of the performance. Stage fright is ultimately a product of self-regard in which the performance has become more about the performer than the music or the audience. The idea of giving; that in performance you are transmitting something greater than yourself; has been supplanted by the fear that you will be exposed as not good enough.

So what can you do?

Stage fright is essentially a problem of expression and preparation and there are many creative solutions to nerves. Here are some ideas to try.

Here is a short video from the Ted Talks about stage fright. It’s worth watching to consolidate what you know and ends with a helpful breathing exercise.

The scale systems by Carl Flesch and Ivan Galamian are by no means the only in existence, but they have been the most widely used by violin students and teachers for many years. The systems are different in profound ways and each has valid applications for the modern violinist.

Both Galamian and Flesch were master teachers, each from a long line of violin pedagogues. Carl Flesch (1873-1944) was born in Hungary. He began playing at the age of five, and was accepted into the Vienna Conservatoire aged just 13. His students include Henryk Szering, Ida Haendel, Ginette Neveu and Max Rostal.

Flesch believed that violin teaching before Sevçik had been flawed; that Sevçik had proven that advanced technique could be a result of training and not genius. He maintained that all violinists should be schooled sequentially and defined each technical step clearly on the principle that tone quality, intonation, technical proficiency, listening and hearing skills are all things that can be taught.

Ivan Galamian (1903-1981) studied in Moscow. His concert career was short. It was speculated that this was due to chronic kidney stones which left him in great pain after every performance. Galamian used to chain-smoke his way through lessons, perhaps to diminish the pain and keep it from interfering with his teaching. He had moved to New York as the Russian Revolution gathered pace, and once there he founded the Meadowmount Summer Violin School. He also held prestigious teaching posts at the Curtis Institute and the Julliard School of Music. This clip gives some insight into Galamian’s relationship with his students.

Galamian was a consummate teacher, and once remarked, “One must make a choice – either a solo career or a teaching career. You cannot do both equally well. One or the other will suffer.” He explained his enthusiasm for teaching, “Ever since I was a child I have been interested in the how-to-do-it aspect.”

Galamian saw problems in the way violin students were taught. He disagreed with the idea that the violin must be taught from a physical angle, stating that technical mastery depends on the control of mind over muscle, rather than agility of fingers. He also felt the interdependence and relationship of the many technical elements was neglected.

Here is a video of a lesson given by Galamian, cigarette in hand, to a young Joshua Bell. Between the fourth and fifth minute, you can here a G major three-octave scale, from the Galamian scale system.

In order to see the difference in the two systems, let’s have a look at the way they are laid out.

Flesch’s Skalensystem deals with one key at a time. The entire study for that key is contained in one place in the book in sections numbered 1 through 12.

In the new edition there is some attempt to cover four-octave scales but it is not very comprehensive and serves to further overwhelm the student with material. As you progress through the book, different rhythms, bow strokes and bowings are suggested for the study of each key.

Each scale from B flat major up uses the same fingering, always beginning on the second finger. This way, the spacing is learned for every position and intervals remain the same for almost every major and every minor key.

Flesch instructs that scales should be practised slowly for intonation and rapidly for facility, and that the key must be changed every day. In the modern edition, Max Rostal suggests in his preface that the key may be changed twice a week. He also explains that focus should be on the legato bowing with bowing exercises added later, as the initial goal is to develop left hand technique. Legato playing allows for the development of inaudible shifting and controlled string crossing. Rostal also suggests less time consuming programmes for studying the system, selecting parts of the designated key each day.

This is all perhaps rather overwhelming. Particularly since the advent of television and Internet we all have much less time to practice. This system would be ideal if within 45 minutes each day we were able to cover a complete key as Flesch suggests, but it is not actually possible to do! What can happen is a lot of arduous, unrewarding work and the onset of a deep hatred of scales because Flesch just seems too difficult.

The Galamian system, Contemporary Violin Technique is more visually approachable, and is also less prescriptive. It comes in two volumes (Vol. 1, Vol. 2).

Volume One covers single stopped scales. The sections are:

This book is written with only the note heads and no note values. There are several suggested basic bowing patterns to work from. There is then a second book, which contains rhythmic variations for the bowing patterns. Galamian also uses more diverse fingerings rather than applying one fingering to every key.

This book is written with only the note heads and no note values. There are several suggested basic bowing patterns to work from. There is then a second book, which contains rhythmic variations for the bowing patterns. Galamian also uses more diverse fingerings rather than applying one fingering to every key.

The main feature of the Galamian scales which differs from the Flesch, is the Galamian turn. At the start of the three octave scales, the third note is played immediately after the first, then back to the second and first notes before ascending, so a G major scale would start like this: G B A G A B C D and so on. This turn is repeated at the end of the scale. The result of this is that every three-octave scale has exactly 48 notes, 24 on the way up and 24 on the way down. This means that the notes are divisible by 3, 6, 8, 12 or 24 notes per bow. This facilitates Galamian’s Acceleration Series. He suggests the student puts on a metronome at crotchet (quarter note) = 60 or 50, or even slower, and begins the scale slurring two quavers (eighth notes) per beat. The scale then progresses to three notes per beat, then four, six and so on. The left hand speeds up and the right hand maintains the same bow speed, but with faster, more fluid string changes. This fulfils Rostal’s suggestion that the legato playing to facilitate development of left hand technique is most important.

Once this is done, bowing patterns can be imposed on the scale. In this way, a strong foundation is laid in the left hand for good intonation in every position, and the student also has a daily outlet for working on bowing techniques.

The less prescriptive fingerings of the Galamian book are useful in repertoire. There is no correct fingering for scales or pieces. In the Flesch system, scale patterns are memorised easily because the fingering remains the same, but fingerings serve a purpose. The more fingerings a student can learn, the more artistic choices are available.

The Galamian book is also more approachable for intermediate level players. The Flesch book looks frankly impossible to the less ambitious or advanced player, but with Galamian it’s possible to start at whatever level you have reached.

The second volume of Galamian’s scale system comprehensively covers double and multiple stops. My violin professor, Howard Davis, who had studied with Frederick Grinke, himself a pupil of Carl Flesch, used to prescribe ten minutes a day of thirds, ten of sixths and ten of octaves, played with a metronome at crotchet = 60, four beats to a note. “That’s all you need to do,” he’d say.

The purpose of practising scales is to build technique. The purpose of building technique is to facilitate more beautiful interpretation of repertoire, and scales provide the most effective targeting for this. Using scales, the violinist can work on intonation, rhythm evenness of tone, constant bow speed, beauty of tone, relaxation, breath, shifting, posture and many other aspects of playing.

Some students may prefer the stricter layout of the Flesch book, where everything for each key is in one place. Others may prefer the open ended system by Galamian, in which it’s possible to pick and choose what to cover and how. I would suggest that the Galamian system might show improvements more quickly as it is easier to be more random with the approach to practice, giving the brain new problems to solve rather than repeating a section until it is right.

These two books on the study of scales are by no means the only ones available. The newest on the market is by Simon Fischer, who has written two other books of technique, Basics and Practice. His book Scales, is designed to counteract the problems many people suffer when approaching scale practice. Fischer maintains that since the main purpose of scale practice is to build technique, it is important to work on the elements of the scale even more than on the complete scale. Instead of the traditional scale system, he gives a detailed analysis of how intonation works and provides exercises to develop shifting, string crossing and intonation within the scale. He then develops the practice in a streamlined way, connecting the whole scale together.

With any scale system, the trick is to maintain focus, discipline and creativity in practice. Perhaps the best solution is to use several different systems and take what you can from each. Sometimes we want to be challenged, at other times we want to explore.

In the context of violin study, where so much knowledge is passed on verbally in lessons, it is a huge privilege to have these works available to give us a window into the teaching of some of the greatest violin teachers, who’s approach would otherwise have been diluted or lost altogether.

Pattern building studies for the violin are composed around simple ‘building-block’ phrases and repetitive figures, designed solely to build finger strength, agility and facility. There are many such studies in the violin repertoire, the best of which are the study books by Sevçik and Schradieck which, when practiced correctly, build left hand technique and strength comprehensively and incrementally. These books are essential supplementary material for scale and study practice and contain repetitive drills, covering all possible approaches to any particular problem.

Pattern building studies for the violin are composed around simple ‘building-block’ phrases and repetitive figures, designed solely to build finger strength, agility and facility. There are many such studies in the violin repertoire, the best of which are the study books by Sevçik and Schradieck which, when practiced correctly, build left hand technique and strength comprehensively and incrementally. These books are essential supplementary material for scale and study practice and contain repetitive drills, covering all possible approaches to any particular problem.

Study of the pattern building exercises in these books hones basic skills, resolves the technical issues which hamper musical performance and leads to large jumps in technical improvement. Where a repertoire-rich practice diet can miss out the basics, covering these supplementary studies, which are sometimes shunned because they seem dull and dry, gives solid technique and avoids the need for rehabilitation in the future.

In his 1986 introduction to the Flesch Skalensystem, violinist Max Rostal explains that the best way to build intonation and facility is by practicing technical difficulties in isolation. For example, he says a problem with intonation or shifting must be approached by deciphering and improving how the wrong note is accessed. Since Sevçik’s Opus 8, Studies in Changes of Position and Preparatory Scale Studies, is the most comprehensive book on shifting that exists, there is therefore no reason why a student wishing to improve shifting, intonation and facility would avoid it.

Pattern building exercises may be considered old fashioned by some teachers, but they are designed with a deep understanding of how the muscles and brain learn, an understanding which can be explained with recent discoveries in neurological science.

In 1959, William Primrose, the famous viola player who performed and recorded chamber music with Jascha Heifetz, published his book, Technique is Memory. In his introduction he states, “This book is not for geniuses.”

Primrose’s book is based entirely on the study of left hand finger patterns. He explains that, “To know when to put a finger in a given place at a given time; to know also its position relating to the other three fingers at that particular place and time, is to know all that is necessary in the search for accuracy.

“Technique is a means to an end,” he says. “There is no short-cut to efficiency on any instrument that will bypass systematic practice.”

His book is thoroughly systematic. It covers every key in every position, aiming to cover the entire topography of the fingerboard. Primrose explains that if technique is memory, it follows that the eye plays an important role in pattern building practice. The route is eye to brain, brain to finger, finger (or the sound produced by it) to ear and ear to brain. In his book, numbered groups of fingers are connected with symbols, designed to be filled in by the student in colour; red for semitones, green for whole-tone sequences and so on. Each scale is practiced very slowly at first and then repeated faster. Primrose concludes that when study of the book is complete, the student should be able to recall verbally, whilst away from the instrument, the finger pattern of any scale in any part of the instrument.

The violin has a range of about four and a half octaves, or 54 semitones. There are at least 100 different places in which to play the 54 semitones, since many are playable in more than one place. It makes sense then that detailed study of the left hand patterns is required to build good intonation and knowledge of the fingerboard. We talk about muscle memory, but that is quite a lot for the muscles to remember!

Ivan Galamian explains in his book, The Principles of Violin Playing and Teaching (1962), that the foundation upon which the technique lies rests upon the correct relationship of the mind to the muscles, the smooth, quick and accurate functioning of the sequence in which the mental command elicits the desired muscular response. The greater this correlation, the greater the facility. Interestingly, neurological science has only recently been able to prove this idea, which the great violin teachers already understood and implemented in their pattern building approach.

|

Further recommended reading:

|

As recently as the 1980’s neuroscientists discovered the importance of a neural insulator called myelin. Every human skill is created by chains of nerve fibres carrying electrical impulses. As these impulses are repeated, myelin, or white matter, wraps the fibres in the same way that we insulate an electrical wire. This insulation makes the signal stronger and faster by preventing the electrical impulses from leaking out.

When we practice a pattern building exercise, a neural circuit is fired and the myelin responds by wrapping layers of insulation around it. Each new layer adds a bit more skill and speed. Skill can therefore be describes as a cellular insulation which wraps neural circuits. Experiences where you are forced to slow down, make errors and correct them, repeat the same constructive piece of study many times; which is exactly how you would be approaching an exercise from a book of Sevçik; result in greater fluency.

In an interview with Daniel Coyle, author of The Talent Code, Robert Bjork, chair of UCLA explains, “We tend to think of our memory as a tape recorder but that’s wrong. It’s a living structure, a scaffold of nearly infinite size. The more we generate impulses, encountering and overcoming difficulties, the more scaffolding we build, the faster we learn.”

The more you fire a particular circuit, the more myelin optimises that circuit, and the stronger, faster and more fluid your playing will become, just as Galamian said. Targeted practice of pattern building exercises is effective precisely because the best way to build good circuits is to fire them over and over again. This is the science behind the 10,000 hour rule; the theory that to acquire mastery in any given skill, 10,000 hours of targeted, concentrated practice is required.

In his book, Practice, violinist and teacher Simon Fischer also describes how improving technique means building an ever larger collection of automatic, unthinking actions that have a desired, not an undesired effect.

Pattern building exercises are a chance to linger in the early stages of technical acquisition, maintaining a child-like curiosity for the instrument. Small children love this sort of skill mastery. A child will never seek reasons, justifications or explanations the way older students and adults do. Children are physical learners, and instinctively understand that technique facilitates more genuine responses to music. When we play musically and with inspiration, a better feeling comes into the muscles than when we play mechanically. Passion and persistence are key.In his book, Practice, violinist and teacher Simon Fischer also describes how improving technique means building an ever larger collection of automatic, unthinking actions that have a desired, not an undesired effect.This is the science behind the 10,000 hour rule; the theory that to acquire mastery in any given skill, 10,000 hours of targeted, concentrated practice is required.

To avoid over-practicing, or falling into the trap of playing these exercises mechanically, always practice with a goal in mind. What would you like to play better? Use the exercises according to your needs. Practice them regularly but only for a short, concentrated period, optimising your circuit building. The objective is not to learn a particular book of Sevçik or Schradieck in its entirety, or to get through all of the exercises as fast as possible; the reward is in the increased complexity of personal ability which comes as a result of mixing and matching the exercises with scales, studies and repertoire.

The Schradieck exercises are extremely helpful in that their focus on left hand co-ordination can be added to with variations in bowing style and technique. This exponentially increases the benefit of the work, and makes it more fun and more rewarding. In a postscript to Galamian’s Principles of Violin Playing and Teaching, former student, Elizabeth A H Green recalls how Galamian used studies as a “panorama of pertinent technique.” Various rhythms and diverse bowings were superimposed on left hand work, always creating problems for the mind to solve. The variations would become gradually more demanding, and she describes transcending technical problems as the exercises resulted in rapidly accelerated learning.

[gview file="https://www.violinschool.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/Henry-Schradieck-School-of-Violin-Technique-Book-1.pdf"]

Finally, these books of pattern building studies are designed to fulfil a purpose: to provide a means of study for thoroughly learning the basis of a strong, reliable technique and an understanding of the geography of the instrument. Be careful to avoid becoming obsessive or overly perfectionist, as this will render them dull and counterproductive. This kind of analytical work can be stultifying for right-brained and creative thinkers and should only be approached in a creative, explorative and musical way. Perfectionism seems a natural outcome of something so thorough as a volume of shifting exercises, but perfectionist expectations lead to a detachment from the body and a self-apologetic approach. Repetitive work becomes less effective when we are bored, so try a random approach to repetition, working alternately on several different exercises and mixing up bowing patterns and rhythms.

| To understand more about the value of repetitive practice within a randomized schedule and with variations of rhythm and bowing, read this post by clarinetist Christine Carter. |

Make sure you know the reason for practicing each exercise; remind yourself of your intention for practicing; observe your work carefully to ensure you are getting good results in small, concentrated time slots; play musically and enjoy the process of discovery.

Finding new music to learn is a huge part of studying the violin, and if you want to expand your music library without spending a fortune there are several ways to find free easy violin sheet music.

During your lessons, your teacher will guide your choice of repertoire and help you progress through different styles and skill levels. However, discovering new music for yourself, even with a teacher’s help, can be an overwhelming task, and buying new music books only to find you don’t like the pieces can be expensive.

A simple Google search, “Free Easy Violin Sheet Music,” yields a staggering 731,000 results. But it’s not that simple. There is a reason why good quality sheet music is not cheap.

[MM_Member_Decision isMember='false']You will need to register for ViolinSchool membership in order to read the rest of this article! Click here to see all the benefits of becoming a member, and to join today![/MM_Member_Decision][MM_Member_Decision membershipId='1']You currently have a free account! To read the rest of this article, you will need to register for ViolinSchool membership. Click here to see all the benefits of becoming a member, and to join today![/MM_Member_Decision][MM_Member_Decision membershipId='2|3']Firstly there is the question of copyright. Any piece of music published in the last 70 years is still in copyright and photocopying it or downloading it from the Internet is illegal. Easy versions of many familiar tunes are available as arrangements, but most arrangements are still in copyright. Secondly, whilst music published more than 70 years ago is now in the public domain and can be legally downloaded and copied, many old scores and parts contain editing marks from the early 1900s which are confusing, obsolete and often stylistically incorrect. Some of the arrangements or new compositions which are available to download for free are of questionable musical quality. Some baroque music appears in facsimile - the original handwritten manuscript - which is interesting to see, but not much use.

It is also difficult when you are starting out on the violin to know which music is suitable for the level you have reached. So where should you look, what can you expect and how do you find music of the right standard?

Taking an old-fashioned view, your local library is a good place to start your search for free easy violin sheet music. Your local branch may not stock sheet music, but it’s very likely that a city branch will. Ask what they have on their catalogues. It’s free (unless you forget to renew it) and it saves printing costs.

If you have a friend who is also learning the violin, ask them if they would like to exchange music, or if they would let you have any they no longer need.

There are also many online resources available, covering a huge range of repertoire from Christmas carols and folk songs to sonatas and concertos.

[gview file="https://www.violinschool.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/5.pdf"]

A small number of websites offer free easy violin sheet music to download legally. The most comprehensive is IMSLP, the International Music Score Library Project. IMSLP is a huge archive of public domain scores and parts. You can search by composer or instrument, although it is sometimes simpler to do a Google search of the piece you want, “Handel violin sonata, IMSLP” for example. Much of this music is more advanced, but if you know what to look for, there is something for everyone.

[gview file="https://www.violinschool.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/1.pdf"]

One way to source repertoire could be to look at past and current exam board syllabuses. The Sicilienne from Sicilienne and Rigaudon in the style of Francoeur by the notable violinist Fritz Kriezler is on the ABRSM Grade 4 syllabus 2012-2015, which gives you an idea of the difficulty level. It’s also available on IMSLP. The Trinity Guildhall syllabus is available online and contains guidance for scales and technical work as well as suggested pieces.

Virtual Sheet Music is another website with free music downloads, although these are more limited. Pieces are rated with clear skill levels and reviewed with stars. There are free downloads of Christmas carols and easy arrangements of classical melodies such as Beethoven’s Ode to Joy. If you want to stretch your budget a little, $37.75 for a year’s membership entitles you to unlimited sheet music downloads.

[gview file="https://www.violinschool.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/3.pdf"]