Sight-reading is an important skill that you should be developing regularly during your usual violin practice sessions. A good approach is to try at least one new piece of music every day (or every time you practise). If you have lots of time to practise (e.g. 2 or more hours per day), then of course you can do more than that!

Sight-reading is an important skill that you should be developing regularly during your usual violin practice sessions. A good approach is to try at least one new piece of music every day (or every time you practise). If you have lots of time to practise (e.g. 2 or more hours per day), then of course you can do more than that!

Sight-reading practice doesn't have to take long. You can just choose a very short piece of music to read. Try to get into the habit of playing something new 'at sight' as often as you can. If you're a member of ViolinSchool, you can start with our library of sight-reading exercises - if you have time, try a new one every day!

When it comes to developing the skill of sight-reading, consistency and regularity of practice is far more important than length or difficulty. If you practise sight-reading simple pieces a lot, then your sight-reading skills will improve, and you'll find it much easier when you eventually try to sight-read longer and more difficult music.

But if you start trying to sight-read repertoire that's too advanced for you, you will struggle to develop your skills correctly, and you may become demotivated. So be sure that you're not trying to tackle pieces that are too hard.

So you're in your practice room and you've chosen the piece or exercise that you want to use to develop your sight-reading skills.

But what do you do next?

Here's a useful method we've developed that will help you stay focused in your practice:

1) TRY IT!

Glance over the whole piece that you're about to play, and make sure you consider everything on 'The Sight-Reading Checklist', so that you're clear about exactly what you need to do.

Glance over the whole piece that you're about to play, and make sure you consider everything on 'The Sight-Reading Checklist', so that you're clear about exactly what you need to do.

Then, try playing it through once - straight through from beginning to end. Don't stop, don't go back, just perform it as best you can.

2) PRACTISE IT!

Now it's time for a second look. Play through the piece again, but do it slowly, carefully, and fastidiously... this time, you can stop and practise any bits that need practising.

3) METRONOME IT!

Play it through again - this time with a metronome! One of THE most important things to consider when you're sight-reading something is the timing - particularly the pulse of the music and the rhythm of the notes.

Don't worry about making mistakes - it's usually much more important for the music to STAY IN TIME than it is to get every note 100% right.

This is especially the case if you are playing with other people; even if the notes aren't totally accurate it's still possible to keep playing together, but if one person gets the timings wrong then the whole piece will fall apart!

4) PERFORM IT!

Imagine you are giving a concert, and try to give the best performance you possibly can - make it confident, convincing, accurate, and musical. Remember, you're now practising performing as well as sight-reading... so whatever you do, don't stop! You can always go back and fix any mistakes afterwards.

**

Remember this list to help keep your sight-reading practice efficient and effective!

**

Always remember that sight-reading is a learnable skill, so the more you do it, the better you'll become. Sight-reading is a critical skill for succeeding in a group environment, so you'll also rapidly build up your confidence - which is especially useful if you're playing with other people.

By making time for sight-reading on a regular basis and ensuring that you are always practising in a clear, ordered way, you will also be improving your overall musicianship and performance skills, as well as your violin technique.

All about sight-reading, why it's important, and a checklist to help you get things right first time!

From Sight to Sound ...

'Sight-reading' is the term used to describe the reading and performing of music without any previous preparation; to sight-read is to play, or sing, or 'hear in our heads' (audiation) the notated music we see ... at first sight!

Sight-reading is an incredibly important skill; the better you can sight-read, the quicker you can learn new pieces, the more music you can play! It also means that you can focus more on technique, interpretation and performance practice instead of merely note-learning and rhythm-deciphering!

The aim is to sight-read with such accuracy, musicality and conviction that the listener, real or imaginary, has no idea you are sight-reading! It should sound as if you've been practising it for months! And it's not only the pitches and the rhythms you need to get right. Every aspect of the notation needs to be realised - dynamics, articulations, tempo markings, performance directions, bowings etc. Many aspects of music-making are not notated but rather 'felt' - character, style, emotion, atmosphere, phrasing etc. - these aspects should also be realised as fully and convincingly as possible.

At ViolinSchool, we think sight-reading is such an essential skill that we are releasing a new piece of sight-reading every single day! Ideally, you should aim to sight-read something every time you practise. The more you do it the better you will get!

Download this Checklist as a PDF!

Skilled sight-readers will always be looking ahead, processing information ahead of time and storing it in their short-term (working) memory. As you develop your sight-reading skills, you'll get better at knowing when to look ahead and by how much. Factors such as tempo, visual and technical complexity, predictability, print size (!), will dictate how much you are able to look ahead. Long notes and rests are your friends!

And, in order to sight-read well, you need to be able to play without looking at your instrument, or at your hands and fingers.

We hope you enjoy developing your sight-reading with ViolinSchool's Sight-Reading Exercises! Try each excerpt a few times, and at least once with a metronome! If the excerpt seems too difficult, then try playing each note, one by one, at a slow tempo, without worrying about the rhythm, dynamics, articulation, bowing etc. If it seems fairly easy, then imagine you are in a concert, and perform it first time, as perfectly, musically, and confidently as you can.

Happy sight-reading! 🙂

When you first start learning the violin, you will also start learning to read music.

To a musician, written music is like an actor’s script. It tells you what to play, when to play it and how to play it.

Music, like language, is written with symbols which represent sounds; from the most basic notation which shows the pitch, duration and timing of each note, to more detailed and subtle instructions showing expression, tone quality or timbre, and sometimes even special effects.

What you see on the page is a sort of drawing of what you will hear.

The notes in Western music are given the names of the first seven letters of the alphabet: A, B, C, D, E, F and G. Once you get to G the note names begin again at A.

The notes of the violin strings without any fingers pressed down, which are commonly known as the open strings, are called G, D, A and E, with G being the lowest, fattest string and E the highest sounding, finest string.

When notated, the open string sounds of the violin look like this:

You will see that the notes are placed in various positions on five parallel lines called a stave. Every line and space on the stave represents a different pitch, the higher the note, the higher the pitch.

The note on the left here is the G - string note, which is the lowest note on the violin. The note on the right is the E - string pitch, which is much higher.

The round part, or head of the note shows the pitch by its placing on the stave. Each note also has a stem that can go either up or down.

The symbol at the front of the stave is called a treble clef. The clef defines which pitches will be played and shows if it’s a low or high instrument.

Violin music is always written in treble clef. When notes fall outside of the pitches that fit onto the stave, small lines called ledger lines are added above or below to place the notes, as you can see with the low G - string pitch which sits below two ledger lines.

Once too many ledger lines are needed and the music becomes visually confusing, it’s time to switch to a new clef, such as bass clef.

The numbers after the treble clef are called the time signature. The stave works both up and down (pitch) and from left to right.

From left to right, the stave shows the beat and the rhythm. The beat is the heartbeat or pulse of the music. It doesn’t change.

The music is written in small sections called bars, which fall between the vertical lines on the stave called bar lines.

Some pieces have four beats in a bar, which means you feel them in four time, some have three, like a waltz, and so on.

The time signature shows how many beats are in each bar, and what kind of note each of those beats is.

The rhythm is where notes have different durations within the structure of the bar. This is where pieces can really start to get interesting.

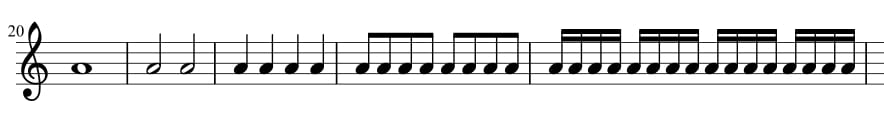

Here we can see a variety of rhythms.

Each of these bars has a value of four beats. The first of the notes above is called a semibreve. It lasts for four beats.

Each of these bars has a value of four beats. The first of the notes above is called a semibreve. It lasts for four beats.

The second is called a minim (or half note, in America) and each minim lasts for two beats. You can see there are two minims in a four-beat bar.

The third example is a crotchet or quarter note. Each crotchet is one beat long.

The fourth rhythm is a quaver, or eighth note, which lasts for half a beat, and the last note value shown is called a semiquaver or sixteenth note, and lasts for quarter of a beat, so sixteen semiquavers fit into a four beat bar.

The smaller notes are written in groups of four so they match up with the beat visually and are easy to read. Each note length has a corresponding symbol to show when there is a rest (silence) of that duration.

The time signature 4/4 shows that there are four beats in each bar (the top 4) and that each of those is a crotchet or quarter note (the lower 4).

The time signature 3/8 would show three (the top number) quaver, or eighth note, (the bottom number) beats in a bar.

As you put your fingers on the strings to play new notes on the violin, the music shows the pitch rising. So the first finger note on each string of the violin would look like this: The note after G on the G – string is called A and is played with the first finger.

The note after G on the G – string is called A and is played with the first finger.

The note after D on the D – string is called E, on the A – string it’s B and on the E – string it’s F.

The first finger in violin fingering is the index finger, unlike on the piano where 1 denotes the thumb.

There are other symbols which show pitch, one of which, the thing that looks like a hash tag, is shown above. This one is called a sharp and the full name of the second note shown on the E – string is F sharp.

You will see these symbols for sharps or flats in the key signature of nearly every piece. The key signature is placed between the treble clef and the time signature and shows you which key or tonality to play in.

As you add the other fingers, you can see below how the gaps on the stave are filled, until you are playing every first position note on your violin. As you build up your fingers one at a time, the pitches on the stave look like this:

The very last note here is played with the fourth finger on the E – string.

It is worth noting at this point that because the pitches of the violin strings are five notes or a fifth apart, each open string note after G can also be played with the fourth finger or pinkie on the previous string, so the A – string note, for example, can be played with the fourth finger on the D –string.

This seems a lot to remember but there are a couple of helpful memory tricks:

The notes in the spaces of the stave, in ascending order, are F, A, C and E, or FACE.

The notes on the lines are E, G, B, D and F. You may remember learning the mnemonic, Every Good Boy Deserves Fun.

You will soon begin to memorise which note corresponds to which sound and finger placement on your violin. Remember that when you learned to read, you were simultaneously studying writing skills.

Try downloading and printing this music manuscript paper, and practice writing out the notes as you learn to play them. Write out the open string notes and practice from your own copy.

Making the connection between writing, reading and playing will speed up and deepen the process of learning.

Soon the note reading will become habitual, and just as you don’t have to process every letter to read a word, you will begin to see the piece as a whole rather than having to read each note and work out where to play it.

As with any new skill, the more you practise and try it out, the more confident you will feel and the sooner you will be reading music fluently.

Sight Reading for Violin

“The ability to sight-read fluently is a most important part of your training as a violinist, whether you intend to play professionally or simply for enjoyment. Yet the study of sight-reading is often badly neglected by young players and is frequently regarded as no more than an unpleasant sideline. If you become a good sight-reader you will be able to learn pieces more quickly and play in ensembles and orchestras with confidence and assurance.” Paul Harris, author of the Improve your sight-reading series.

Sight-reading is a really important skill. We sight-read new pieces in orchestra and duet rehearsals, we get sight-reading tests in exams and auditions; if you can’t sight-read, learning a new piece, or even choosing which piece to learn, is an arduous task. An ability to sight-read well opens up opportunities to enjoy ensemble playing and take charge of your own learning. Good sight-readers are more versatile performers because they are able to assimilate new music and diverse styles very quickly, and to perform with minimal rehearsal time. Learning to sight-read well should be at the top of every violinist’s list of priorities.

The main problem with sight-reading is that we start to see it as separate from our other musical skills and even our basic musicianship. Faced with a piece of sight-reading, we shut down our brain to all of the things we have learned and enjoy about the instrument, and panic.

Fundamentally, sight-reading is the skill of reading music, and how that reading transfers into movement and sound. Sight-reading is a skill, and it is true that the more you do it, the more fluent you will become, but there is no point spending hours trying to improve unless you understand the elements of the skill. It is essentially a mental activity, the message travelling from eyes to brain to fingers, and it is important not to try too hard or you’ll get in your own way! Really successful sight-reading is relaxed, calm and musical.

It is important to practice sight-reading regularly as part of your practice. Once you have grasped the basic concepts, the skill needs constant reinforcement to instil good habits. If you can’t bear to practice on your own every day, arrange to meet friends for ensemble playing and read through new pieces with them.

Only accessible material enables you to acquire the habits that will lead to fluency. Don’t choose to sight-read complex material, start with really basic music and build up to more complicated pieces gradually. Get as many sight-reading books as you can so you don’t run out of material. Paul Harris’s graded series, Improve Your Sight-reading is excellent, because it starts by breaking down the basic components of pulse, rhythm and melody, and the exam boards have books of specimen tests available. You could even use the pieces or sections of pieces you don’t know in any book you are working from. As a rough guide, it’s an idea to start learning to sight-read using music which is much easier than your current repertoire.

Practice sight-reading slowly; learn the positions of the notes on the stave and how they relate to your left hand finger patterns. Scales are great for learning finger placement. Make sure you know some basic theory concepts such as key and time signatures. Don’t be fazed if you come across something you’ve not seen before. That happens to everyone. Just find out what it is.

The first thing to do when faced with a piece of music you haven’t seen before, because that’s all sight-reading is, is to prepare the piece.

As you become more experienced, this process will speed up and you will be able to gauge most of the information you need by visually scanning the music before you start.

Successful sight-reading is largely a matter of good quality concentration. Your mindset and focus as you look at the page is the most important factor. Notice your eyes. Visual steadiness is crucial. Relax your eyes and don’t let them fidget and flit about, losing connection with what you are doing. Instead of going through the motions of reading, really focus. True concentration is difficult to maintain for long, but you don’t have to work hard, merely practice awareness. The second you notice your concentration has gone, you have already refocused yourself.

Problems generally arise when we are not ready for the notes as they arrive. Your eyes are looking at a note and you are also playing that note, and sometimes it’s happening so fast that your brain can’t process the information. Then you start to feel that blind panic which makes you hate sight-reading. The trick is to continually read ahead. Keep your eyes moving a few beats in front of where you are playing. Sight-reading in this respect is actually the process of visually memorising short snippets of music you are about to play whilst playing something else. This allows the fingers to be ready for the notes as they arrive, and suddenly you are playing fluently.

Reading ahead enables you to look at the music in bigger chunks. Instead of looking at each note as a separate event, you start to see how its rhythm fits into the beat, and melodically where scale and arpeggio patterns appear and how other intervals fit in.

Don’t react to mistakes. As soon as you give too much attention to a mistake, your concentration is no longer on what you are doing, and the chances are you are just about to make another mistake, and another. Decide to play all the way through without stopping. Keep going at a steady tempo and don’t worry about a dropped note. Imagine how quickly an orchestra would fall apart if every player who made a mistake hesitated or went back to correct it. Soon nobody would be in the same place at all. Prioritise. If on your first try you are able to keep the pulse but play all of the wrong notes, that’s a good start.

So as you prepare to play the piece remember:

Sight-reading is simply the process of playing a piece of music you haven’t seen before. Don’t separate it from your other musical skills in your mind; approach it with enthusiasm, curiosity and confidence. And now you have the tools to learn how to sight-read, never dismiss sight-reading practice as dull and unnecessary. It is one of the most fundamental skills a violinist needs.

“To rely on muscular habit, which so many of us do in technique, is indeed fatal. A little nervousness, a muscle bewildered and unable to direct itself, and where are you? For technique is truly a matter of the brain.” Fritz Kreizler, violinist and composer 1875 -1962

Visualisation, the process of creating compelling images in the mind, is one of the most valuable tools for learning and integrating skill, building confidence and achieving success, yet we constantly underuse it in our lives and our violin practice.

Visualisation accelerates the learning of any skill by activating the power of the subconscious mind, focussing the brain by programming the reticular activating system - the filter which mediates information and regulates brain states - to seek out and use available resources, and by raising the level of expectation, motivating a better result.

Scientists have found that the same regions of the brain are stimulated when we perform an action and when we visualise performing that action: If you vividly imagine placing your left hand fingers on the fingerboard of your violin, your brain activates in exactly the same way as if you were actually doing it – your brain sees no difference between visualising and doing. This research is used to great effect to help stroke patients reactivate muscles that have lost their facility: It has been found to be possible to build strength in a muscle that is too weak to move by simply repeatedly imagining the movement.

[MM_Member_Decision isMember='false']You will need to register for ViolinSchool membership in order to read the rest of this article! Click here to see all the benefits of becoming a member, and to join today![/MM_Member_Decision][MM_Member_Decision membershipId='1']You currently have a free account! To read the rest of this article, you will need to register for ViolinSchool membership. Click here to see all the benefits of becoming a member, and to join today![/MM_Member_Decision][MM_Member_Decision membershipId='2|3']The process of visualisation, which was initially dismissed by many as unfounded, is described in W Timothy Gallwey’s 1974 book, The Inner Game of Tennis.

“There is a far more natural and effective process for learning and doing almost anything than most of us realize. It is similar to the process we all used, but soon forgot, as we learned to walk and talk. It uses the so-called unconscious mind more than the deliberate "self-conscious" mind, the spinal and midbrain areas of the nervous system more than the cerebral cortex. This process doesn't have to be learned; we already know it. All that is needed is to unlearn those habits which interfere with it and then to just let it happen.

Visualisation simply makes the brain achieve more. Sports psychologists and peak performance experts have been popularising the technique since the 1980s, and it has been integrated into almost all mainstream sports and performance coaching, success programmes and business training.

Athletes using guided imagery and mental rehearsal techniques can enhance their performance by creating mental images to intend the outcome of a race. With mental rehearsal the body and mind become trained to actively perform the skill imagined. Repeated use of visualisation builds experience and confidence under pressure, maximising both the efficiency of training and the effectiveness of practice. This principle applies to learning anything new. According to Jack Canfield, in his 2004 book, The Success Principles, Harvard University researchers found that students who visualised tasks before performing them, performed with nearly 100% accuracy, where those who didn’t use visualisation achieved only 55% accuracy. This is also true when applied to the process of learning the violin, both during practice time and performance.

“Fortune favours the prepared mind.” Louis Pasteur, chemist and microbiologist, 1822 - 1895

Most of us are familiar with the idea of reading ahead in the music, or of hearing a note or pitch before playing it. Visualisation - not only conceiving of a phrase before playing it, but vividly imagining the sound, how it feels, where the fingers will fall, how the hand will move in a certain shift and even how the performance will go - is a much deeper way of mentally absorbing and preparing the information. It is also one of the best ways to rid your practice of monotonous repetition and develop awareness of your musical actions.

It’s all very well knowing how great visualisation can be, but how do you go about it? What happens if you close your eyes and don’t seem to be able to see anything?

There are two different ways of visualising, depending on your brain type, both of which are absolutely legitimate. Some people are what psychologists refer to as eidetic visualisers. When they close their eyes they see things in bright, clear, three-dimensional, colour images. The majority of people, however, are noneidetic visualisers. This means they don’t really see an image as much as think it. THIS WORKS JUST AS WELL!

Before we look at how we can apply visualisation techniques in violin practice, let’s look at an example exercise from The Inner Game of Tennis, in which the aim is to hit a stationary target with a tennis ball:

“Place a tennis-ball can in the backhand corner of one of the service courts. Then figure out how you should swing your racket in order to hit the can. Think about how high to toss the ball, about the proper angle of your racket at impact, the proper weight flow, and so forth. Now aim at the can and attempt to hit it. If you miss, try again. If you hit it, try to repeat whatever you did so that you can hit it again. If you follow this procedure for a few minutes, you will experience what I mean by "trying hard" and making yourself serve. After you have absorbed this experience, move the can to the backhand corner of the other service court for the second half of the experiment. This time stand on the base line, breathe deeply a few times and relax. Look at the can. Then visualize the path of the ball from your racket to the can. See the ball hitting the can right on the label. If you like, shut your eyes and imagine yourself serving, and the ball hitting the can. Do this several times. If in your imagination the ball misses the can, that's all right; repeat the image a few times until the ball hits the target. Now, take no thought of how you should hit the ball. Don't try to hit the target. Ask your body, Self 2, to do whatever is necessary to hit the can, then let it do it. Exercise no control; correct for no imagined bad habits. Having programmed yourself with the desired flight of the ball, simply trust your body to do it. When you toss the ball up, focus your attention on its seams, then let the serve serve itself. The ball will either hit or miss the target. Notice exactly where it lands. You should free yourself from any emotional reaction to success or failure; simply know your goal and take objective interest in the results. Then serve again. If you have missed the can, don't be surprised and don't try to correct for your error. This is most important. Again focus your attention on the can; then let the serve serve itself. If you faithfully do not try to hit the can, and do not attempt to correct for your misses, but put full confidence in your body and its computer, you will soon see that the serve is correcting itself. You will experience that there really is a Self 2 who is acting and learning without being told what to do. Observe this process; observe your body making the changes necessary in order to come nearer and nearer to the can, Of course, Self 1 is very tricky and it is most difficult to keep him from interfering a little, but if you quiet him a bit, you will begin to see Self 2 at work, and you will be as amazed as I have been at what it can do, and how effortlessly.”

You can already see how this same exercise might be applied to practising a particular shift or bow stroke, any specific element of your piece that requires a certain physical movement to gain a result.

Here are some more practice and performance ideas from The Musician’s Way, A Guide to Practice, Performance and Wellness by Gerald Klickstein, 2009

Start using visualisation in your practice. You will find you achieve much better results and increased confidence, you can practice at antisocial hours of the day or night, you can save tired muscles, and you will develop a much deeper, intuitive understanding of the instrument and the music. Visualise, imagine and mentally prepare at least as much as you physically play. As you practice visualising it will become easier to integrate it at speed and under pressure.

Visualisation is counter-intuitive in a culture where we are taught to try, try, try again, but it is without doubt the single most powerful practice technique that most of us don’t use!

“If you cannot visualise what it is you wish to become, then the brain doesn’t have the first clue how to get you there." Chris Murray, Author of The Extremely Successful Salesman’s Club

Pattern building studies for the violin are composed around simple ‘building-block’ phrases and repetitive figures, designed solely to build finger strength, agility and facility. There are many such studies in the violin repertoire, the best of which are the study books by Sevçik and Schradieck which, when practiced correctly, build left hand technique and strength comprehensively and incrementally. These books are essential supplementary material for scale and study practice and contain repetitive drills, covering all possible approaches to any particular problem.

Pattern building studies for the violin are composed around simple ‘building-block’ phrases and repetitive figures, designed solely to build finger strength, agility and facility. There are many such studies in the violin repertoire, the best of which are the study books by Sevçik and Schradieck which, when practiced correctly, build left hand technique and strength comprehensively and incrementally. These books are essential supplementary material for scale and study practice and contain repetitive drills, covering all possible approaches to any particular problem.

Study of the pattern building exercises in these books hones basic skills, resolves the technical issues which hamper musical performance and leads to large jumps in technical improvement. Where a repertoire-rich practice diet can miss out the basics, covering these supplementary studies, which are sometimes shunned because they seem dull and dry, gives solid technique and avoids the need for rehabilitation in the future.

In his 1986 introduction to the Flesch Skalensystem, violinist Max Rostal explains that the best way to build intonation and facility is by practicing technical difficulties in isolation. For example, he says a problem with intonation or shifting must be approached by deciphering and improving how the wrong note is accessed. Since Sevçik’s Opus 8, Studies in Changes of Position and Preparatory Scale Studies, is the most comprehensive book on shifting that exists, there is therefore no reason why a student wishing to improve shifting, intonation and facility would avoid it.

Pattern building exercises may be considered old fashioned by some teachers, but they are designed with a deep understanding of how the muscles and brain learn, an understanding which can be explained with recent discoveries in neurological science.

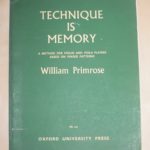

In 1959, William Primrose, the famous viola player who performed and recorded chamber music with Jascha Heifetz, published his book, Technique is Memory. In his introduction he states, “This book is not for geniuses.”

Primrose’s book is based entirely on the study of left hand finger patterns. He explains that, “To know when to put a finger in a given place at a given time; to know also its position relating to the other three fingers at that particular place and time, is to know all that is necessary in the search for accuracy.

“Technique is a means to an end,” he says. “There is no short-cut to efficiency on any instrument that will bypass systematic practice.”

His book is thoroughly systematic. It covers every key in every position, aiming to cover the entire topography of the fingerboard. Primrose explains that if technique is memory, it follows that the eye plays an important role in pattern building practice. The route is eye to brain, brain to finger, finger (or the sound produced by it) to ear and ear to brain. In his book, numbered groups of fingers are connected with symbols, designed to be filled in by the student in colour; red for semitones, green for whole-tone sequences and so on. Each scale is practiced very slowly at first and then repeated faster. Primrose concludes that when study of the book is complete, the student should be able to recall verbally, whilst away from the instrument, the finger pattern of any scale in any part of the instrument.

The violin has a range of about four and a half octaves, or 54 semitones. There are at least 100 different places in which to play the 54 semitones, since many are playable in more than one place. It makes sense then that detailed study of the left hand patterns is required to build good intonation and knowledge of the fingerboard. We talk about muscle memory, but that is quite a lot for the muscles to remember!

Ivan Galamian explains in his book, The Principles of Violin Playing and Teaching (1962), that the foundation upon which the technique lies rests upon the correct relationship of the mind to the muscles, the smooth, quick and accurate functioning of the sequence in which the mental command elicits the desired muscular response. The greater this correlation, the greater the facility. Interestingly, neurological science has only recently been able to prove this idea, which the great violin teachers already understood and implemented in their pattern building approach.

|

Further recommended reading:

|

As recently as the 1980’s neuroscientists discovered the importance of a neural insulator called myelin. Every human skill is created by chains of nerve fibres carrying electrical impulses. As these impulses are repeated, myelin, or white matter, wraps the fibres in the same way that we insulate an electrical wire. This insulation makes the signal stronger and faster by preventing the electrical impulses from leaking out.

When we practice a pattern building exercise, a neural circuit is fired and the myelin responds by wrapping layers of insulation around it. Each new layer adds a bit more skill and speed. Skill can therefore be describes as a cellular insulation which wraps neural circuits. Experiences where you are forced to slow down, make errors and correct them, repeat the same constructive piece of study many times; which is exactly how you would be approaching an exercise from a book of Sevçik; result in greater fluency.

In an interview with Daniel Coyle, author of The Talent Code, Robert Bjork, chair of UCLA explains, “We tend to think of our memory as a tape recorder but that’s wrong. It’s a living structure, a scaffold of nearly infinite size. The more we generate impulses, encountering and overcoming difficulties, the more scaffolding we build, the faster we learn.”

The more you fire a particular circuit, the more myelin optimises that circuit, and the stronger, faster and more fluid your playing will become, just as Galamian said. Targeted practice of pattern building exercises is effective precisely because the best way to build good circuits is to fire them over and over again. This is the science behind the 10,000 hour rule; the theory that to acquire mastery in any given skill, 10,000 hours of targeted, concentrated practice is required.

In his book, Practice, violinist and teacher Simon Fischer also describes how improving technique means building an ever larger collection of automatic, unthinking actions that have a desired, not an undesired effect.

Pattern building exercises are a chance to linger in the early stages of technical acquisition, maintaining a child-like curiosity for the instrument. Small children love this sort of skill mastery. A child will never seek reasons, justifications or explanations the way older students and adults do. Children are physical learners, and instinctively understand that technique facilitates more genuine responses to music. When we play musically and with inspiration, a better feeling comes into the muscles than when we play mechanically. Passion and persistence are key.In his book, Practice, violinist and teacher Simon Fischer also describes how improving technique means building an ever larger collection of automatic, unthinking actions that have a desired, not an undesired effect.This is the science behind the 10,000 hour rule; the theory that to acquire mastery in any given skill, 10,000 hours of targeted, concentrated practice is required.

To avoid over-practicing, or falling into the trap of playing these exercises mechanically, always practice with a goal in mind. What would you like to play better? Use the exercises according to your needs. Practice them regularly but only for a short, concentrated period, optimising your circuit building. The objective is not to learn a particular book of Sevçik or Schradieck in its entirety, or to get through all of the exercises as fast as possible; the reward is in the increased complexity of personal ability which comes as a result of mixing and matching the exercises with scales, studies and repertoire.

The Schradieck exercises are extremely helpful in that their focus on left hand co-ordination can be added to with variations in bowing style and technique. This exponentially increases the benefit of the work, and makes it more fun and more rewarding. In a postscript to Galamian’s Principles of Violin Playing and Teaching, former student, Elizabeth A H Green recalls how Galamian used studies as a “panorama of pertinent technique.” Various rhythms and diverse bowings were superimposed on left hand work, always creating problems for the mind to solve. The variations would become gradually more demanding, and she describes transcending technical problems as the exercises resulted in rapidly accelerated learning.

[gview file="https://www.violinschool.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/Henry-Schradieck-School-of-Violin-Technique-Book-1.pdf"]

Finally, these books of pattern building studies are designed to fulfil a purpose: to provide a means of study for thoroughly learning the basis of a strong, reliable technique and an understanding of the geography of the instrument. Be careful to avoid becoming obsessive or overly perfectionist, as this will render them dull and counterproductive. This kind of analytical work can be stultifying for right-brained and creative thinkers and should only be approached in a creative, explorative and musical way. Perfectionism seems a natural outcome of something so thorough as a volume of shifting exercises, but perfectionist expectations lead to a detachment from the body and a self-apologetic approach. Repetitive work becomes less effective when we are bored, so try a random approach to repetition, working alternately on several different exercises and mixing up bowing patterns and rhythms.

| To understand more about the value of repetitive practice within a randomized schedule and with variations of rhythm and bowing, read this post by clarinetist Christine Carter. |

Make sure you know the reason for practicing each exercise; remind yourself of your intention for practicing; observe your work carefully to ensure you are getting good results in small, concentrated time slots; play musically and enjoy the process of discovery.