The most up-to-date version of this article can be found here - please click here!

Bowed string instruments have been played all over the world for many thousands of years.

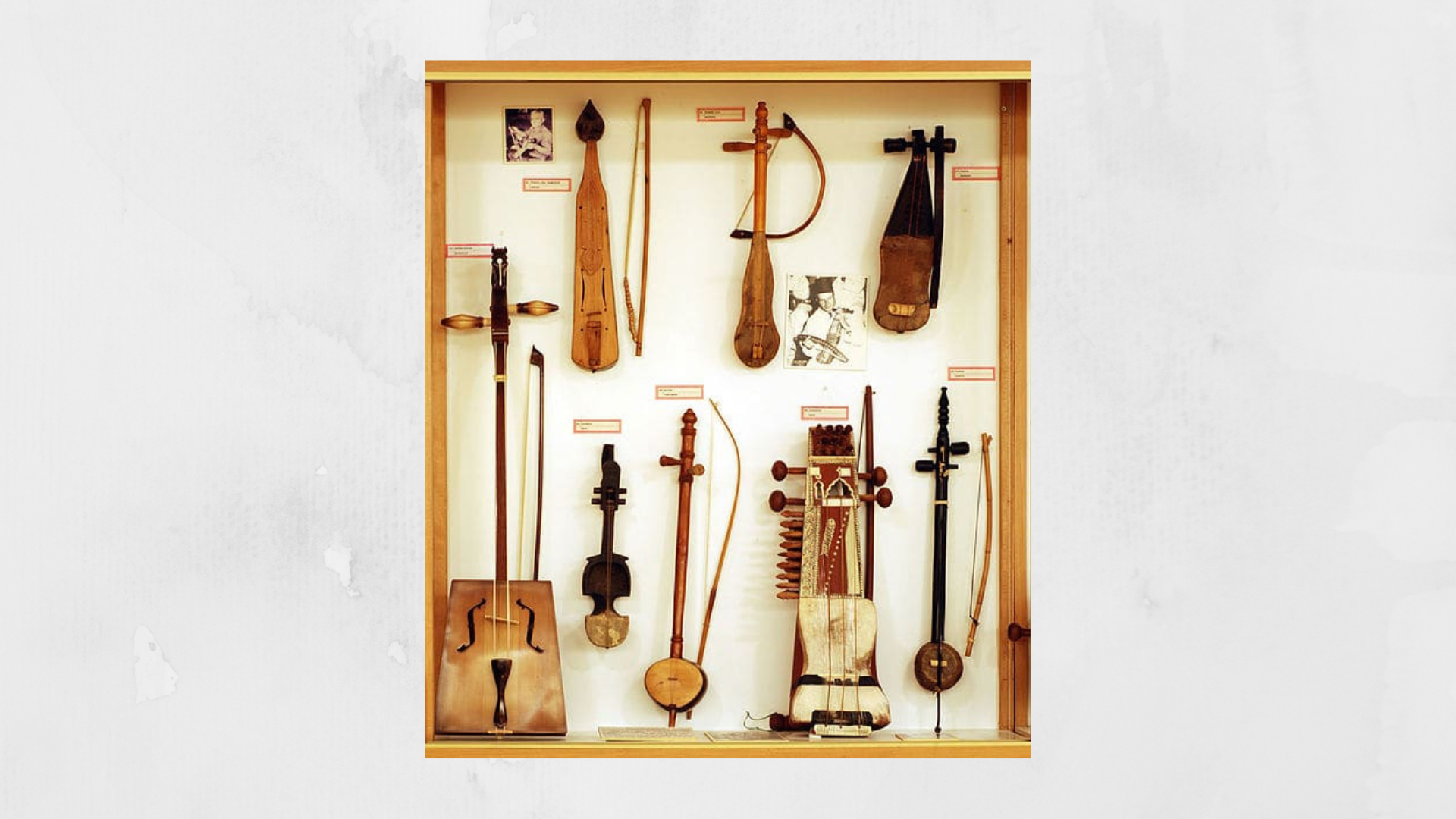

Medieval instruments including the Chinese erhu, the Finnish bowed lyre and the Indian sarangi all had the same basic mechanics as the modern violin, using the principle of a continually resonating string amplified by a hollow body.

In 7th century Greece, there was an instrument called the kithara, a seven stringed lyre, the features of which were very different from the violin.

Early Origins

The development of a musical instrument is rather like the process of evolution. It is gradual and complex, with many of its stages indistinct or undocumented. The history of the violin can be traced back more or less to the 9th century.

One plausible ancestor for the violin is the rabãb, an ancient Persian fiddle which was common in Islamic empires. The rabãb had two strings made of silk which were attached to an endpin and tuning pegs.

These strings were tuned in fifths. The instrument was fretless, its body made from a pear shaped gourd and a long neck.

It was introduced to Western Europe in the 11th and 12th centuries, and the influence of both the rabãb and lyre, along with a constant search for perfection and refinement and the demands of increasingly complex repertoire, led to the development of various European bowed instruments.

Ancestors of the Violin

Forerunners of the violin include the rebec, an instrument based on the rabãb, which appeared in Spain, most likely as a result of the Crusades.

The rebec had three strings and a wooden body and was played by resting it on the shoulder.

There were also Polish fiddles, the Bulgarian gadulka and Russian instruments called gudok and smyk, which are portrayed in frescos from the 11th century.

The 13th century French vielle was very different from the rebec. It had five strings and a larger body, which was closer in shape and size to the modern violin, with ribs shaped to allow for easier bowing.

Confusingly, the name vielle later came to refer to a different instrument, the vielle á rue, which we know as the hurdy-gurdy.

Emergence and Early Variants

There is no reference to the word violin until the reign of Henry VIII, but something very much like the violin existed, and its name was fydyl.

This instrument was played with a fydylstyck, proof that it was bowed and not plucked.

It had only three strings and a fretless fingerboard, and it was used for dancing, in banquets and social events; occasions which required an instrument with a strong sound, held shoulder height for projection.

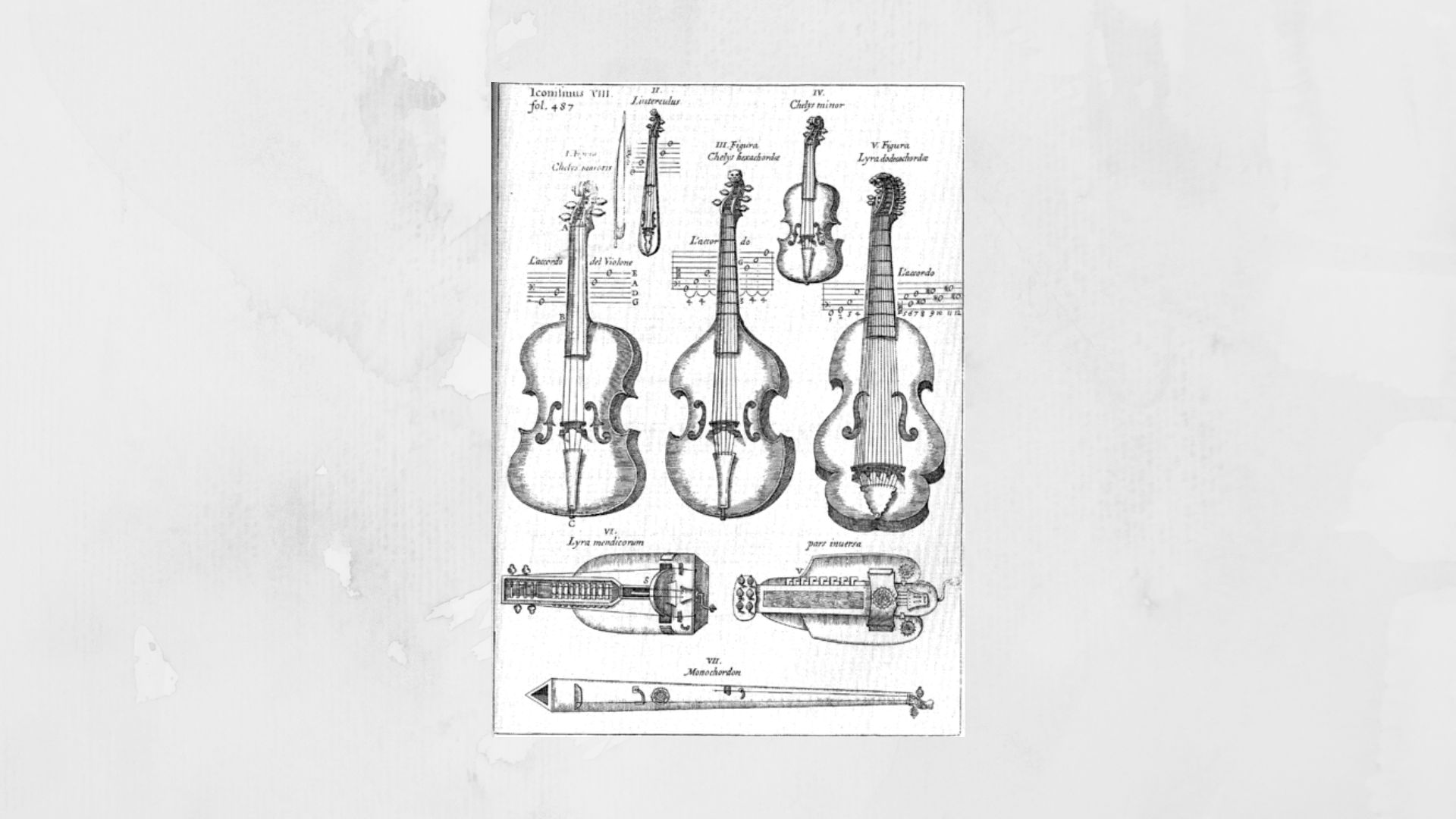

In 15th century Italy, two distinct kinds of bowed instruments emerged. One was fairly square in shape and held in the arms and was called a lira da braccio or viola da braccio, meaning viol of the arm.

This instrument had three strings and was the same general size and shape as the vielle, but the C-shaped sound holes in the body had been replaced by the now familiar F-holes.

The other bowed instrument was a viola da gamba, meaning viol for the leg.

The Rise of the Modern Violin

These gambas were important instruments during the Renaissance period, but were gradually replaced by the louder instruments of the less aristocratic lira da braccio family as the modern violin developed.

The violin first appeared in the Brescia area of Northern Italy in the early sixteenth century.

From around 1485, Brescia was home to a school of highly prized string players and famous for makers of all the string instruments of the Renaissance; the viola da gamba, violone, lyra, lyrone, violetta and viola da brazzo.

The word violin appears in Brescian documents for the first time in 1530, and whilst no instruments from the first decades of the fifteenth century survive, violins are shown in several paintings from the period.

Violins vs Viols

The first clear description of the violin, depicting its fretless appearance and tuning, was in the 1556 Epitome Musicale by Jambe de Fer.

By this time the violin had begun to spread throughout Europe. It was mainly used to perform dance music but was introduced into the upper classes as an ensemble instrument.

Where the viol, which was preferred in aristocratic circles, had been perfect for contrapuntal music and for accompanying the voice, the violin was normally played by professional musicians, servants and illiterate folk musicians.

| "The violin is very different from the viol. First, it has only four strings, which are tuned at a fifth from one to the other, and each of the said strings has four pitches in such wise that on four strings it has just as many pitches as the viol has on five.

It is smaller and flatter in form and very much harsher in sound, and it has no frets because the fingers almost touch each other from tone to tone in all the parts. Why do you call the former Viols, the latter Violins? We call viols those upon which gentlemen, merchants, and other persons of culture pass their time.The Italians call them "viole da gambe,” because they hold them at the bottom, some between the legs, others upon some seat or stool; others [support them] right on the knees of the said Italians, [but] the French make very little use of this method. The other kind [of instrument] is called "violin", and it is this that is commonly used for dance music [dancerie], and for good reason: for it is easier to tune, because the fifth is sweeter to the ear than the fourth is" It is, also easier to carry, which is a very necessary thing, especially in accompanying some wedding or mummery. The Italian calls it "violon da braccia" or "violone" because it is held upon the arms, some with a scarf, cord, or other thing. I did not put the said violin in a diagram, for you can consider it upon [the one for] the viol, joined [to the fact] that few persons are found who make use of it other than those who, by their labour on it, make their living." - Jambe de Fer from the Journal of the Viola Da Gamba Society of America, November 1967. |

The Evolution of the Modern Violin

The viola and cello developed alongside the violin in early 16th century Italy. This new family of stringed instruments gradually took the place of the gambas and viols as new ideas of sound emerged.

It is commonly accepted that the first modern violin was built by Andrea Amati, one of the famous luthiers (lute makers) of Cremona, in the first half of the 16th century.

The first four-stringed violin by Amati was dated 1555 and the oldest surviving of his instruments is from around 1560, but between 1542 and 1546, Amati also made several three-stringed violins.

Amati built his violins using a mould, which meant the measurements became much more precise. He developed a more vaulted shape for the body of the instrument rather than the flat soundboards of the early stringed instruments.

It is speculated that Amati may have studied with Gesparo da Salo in Brescia, but some records show that he was well established in Cremona long before he began making violins, and was in fact older than da Salo.

The Brescian school of luthiers had existed for 50 years before violin making began in Cremona, but the Cremona school gained prominence after 1630, when the bubonic plague swept Northern Italy and eliminated much of the Brescian competition.

Italy had managed to avoid the thirty-year war and development of the instrument continued in a golden age of culture.

Andrea Amati mastered many apprentices, and produced a dynasty of violinmakers, including the Guarneris, Bergonzis, and Rugeris.

His own sons followed him into the trade, and his grandson, Nicoló Amati, the most famous Amati, trained Antonio Stradivarius.

Stradivarius made over 100 instruments, of which roughly two thirds survive. His violins are some of the most imitated by modern makers today.

18th and 19th Century Transformations

The violin, originally an instrument of the lower classes, continued to gain popularity, becoming integral in the orchestra during the seventeenth century as composers such as Monteverdi began writing for the new string family.

The instrument continued to develop between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries, and the surviving historic violins have all undergone alterations.

The violin bow changed dramatically in around 1786, when Françoise Xavier Tourte invented the modern violin bow by changing the bend to arch backwards and standardising the length and weight.

The violin fingerboard was lengthened in the 19th century, to enable the violinist to be able to play the highest notes. The fingerboard was also tilted to allow more volume.

The neck of the modern violin was lengthened by one centimetre to accommodate the raising of pitch in the 19th century and the bass bar was made heavier to allow for greater string tension.

Where classical luthiers would fix the neck to the instrument by nailing and gluing it to the upper block of the body before attaching the soundboard, the neck of the modern violin is mortised to the body once it is completely assembled.

By the 18th and 19th century the violin had become extremely popular. By the late 18th century, makers had begun to use varnished developed to dry more quickly.

This had an impact on the quality of instruments produced. The quality of the wood used in violin making has been affected by the lack of purity of modern water as nearly all substances dissolved in water permanently penetrate wood.

By the 19th century violins were being mass-produced all over Europe. Millions were made in France, Saxony and the Mittenwald, in what is now Germany, Austria, Italy and Bohemia, now part of the Czech Republic.

It is partly for this reason that the violins of the early Italian masters are so prized, so well regarded and so expensive. A Stradivarius violin will now sell for many millions, the most expensive so far on record sold for $16million in 2011.

Modern Violins

More recently, new violins were invented for modern use. The Romanian Stroh violin used amplification like that of a gramophone to boost the volume.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, before electronic amplification became common, these violins with trumpet-like bells were used in the recording studio where a violin with a directional horn suited the demands of early recording technology better than a traditional acoustic instrument.

Electric and electro-acoustic violins have also been developed. An electro-acoustic violin may be played with or without amplification, but a solid bodied electric violin makes little or no sound without electronic sound reinforcement.

Electric violins can have as many as seven strings and can be used with equalisers and even sound effects pedals, a far cry from the exacting acoustic knowledge which created the great violins of the Italian Renaissance.

The circle of fifths is a musical theory tool that has its roots firmly in mathematics. It explores the relationships between those musical intervals that are most pleasing to the ear, based on discoveries made by the mathematician Pythagoras two and a half thousand years ago.

Pythagoras discovered and investigated the most basic facts about frequency and pitch. He found that there were mathematical ratios between notes. The octave, which is the most basic interval, the point at which pitches seem to duplicate, has a natural 2:1 ratio. If a string of a certain length is set in vibration it will produce a particular note. The shorter the string is, the more times it will vibrate per second, once it is set in vibration. When a string vibrates more times per second, the pitch of the note produced is higher. Therefore, if the string is kept at the same tension but its length is halved, it will produce a note one octave higher than the first. The same happens when you blow through a tube of air. A tube twice the length will produce a note an octave lower.

The circle of fifths, sometimes called the Pythagorean circle, is a diagram with twelve points that represent the twelve semitones within an octave. It is a chart rather like a clock face that organises all the keys into a system and can be used to relate them to one another. It is called a circle of fifths because each step of the circle is a perfect fifth from the next. The fifth is the interval that is closest in character to the octave, in that it is more consonant (less dissonant) or stable than any interval except the octave (or the unison).

A perfect interval is one where natural overtones occur. If you play a note on your violin and listen closely, you will hear the pitch you are playing. You will also hear overtones sounding. The most significant of these, or the easiest to hear, is usually the fifth. Where the ratio of frequencies between octaves is 2:1, the ratio of the frequencies of the fundamental to the fifth is 2:3. A perfect fifth is an interval of seven semitones. These seven semitones represent the building blocks from the first note of a scale to the fifth.

Watch this video for a clear description of how the circle of fifths is built.

The circle of fifths is useful because it shows the relationship between the keys, key signatures and chords.

It can be used to:

Now you’ve watched the video on how to make a circle of fifths, have a look at this interactive circle of fifths. You can use it to look at the relationships between chords in any key.

So what is the circle of fifths useful for?

It is possible to learn the order of sharps and flats as they occur in music by using the circle of fifths. You can work out how many sharps or flats are in a key, and also which notes are sharpened or flattened.

If you look clockwise around the circle you will see the order in which the sharps appear in the key signature. When there is one sharp, it is F#. When there are two, they are F# and C#. Three sharps will be F#, C# and G# and so on.

Looking round the circle in an anticlockwise direction shows the order of flats. If there is one flat it is Bb. Two flats are Bb and Eb. Three are always Bb, Eb and Ab, and so on.

In a circle of fifths in the major keys, C major appears at the top of the circle. C major has no sharps or flats. The next key in a clockwise direction is G major. G major has one sharp, which we now know is F#. Then comes D major which has F# and C#. Going in the other direction, F major has one flat, Bb. Bb major has two flats, Eb major has three flats.

Use the interactive circle of fifths above to notice the enharmonic changes this creates in flat keys between, for example F# and Gb. Look at the circle in D major and then in Db major to see how the pitches are renamed. Two notes that have the same pitch but are represented by different letter names and accidentals are described as enharmonic.

The circle of fifths can also be used to work out which keys are related to each other. You can see that the keys on either side of C are F and G. Therefore, the two closest keys to C, which has no sharps or flats, are F, which has one flat, and G, which has one sharp. F and G therefore make up the primary chords in C major. F is chord IV, the subdominant, and G is chord V, the dominant. Using these three chords you can build the standard chord progression IV V I.

The secondary chords are those further away from the note of your key, so in C major, D, A and E would be secondary chords, which means they may appear in the harmony of your piece but are not as strong as the primary chords.

Watch these two clips. They explain how the circle of fifths works in major and minor keys:

The circle of fifths is also useful for understanding chord progressions such as those from dominant seventh chords. Dominant seventh chords have a tendency to want to go towards another chord. They contain a dissonance that melodically and harmonically needs to resolve. The chord that the dominant seventh resolves to is one fifth lower, so A7 resolves to D major, F7 resolves to Bb major, and so on. If you are asked to play a dominant seventh in the key of D, you will start on the note A.

Here is another clip explaining how to use the circle of fifths to understand your scales.

The model of a circle of fifths, with the consequent understanding of chord progressions and harmony and the hierarchy and relationships between keys, has played a hugely important part in Western music.

When you first start learning the violin, you will also start learning to read music.

To a musician, written music is like an actor’s script. It tells you what to play, when to play it and how to play it.

Music, like language, is written with symbols which represent sounds; from the most basic notation which shows the pitch, duration and timing of each note, to more detailed and subtle instructions showing expression, tone quality or timbre, and sometimes even special effects.

What you see on the page is a sort of drawing of what you will hear.

The notes in Western music are given the names of the first seven letters of the alphabet: A, B, C, D, E, F and G. Once you get to G the note names begin again at A.

The notes of the violin strings without any fingers pressed down, which are commonly known as the open strings, are called G, D, A and E, with G being the lowest, fattest string and E the highest sounding, finest string.

When notated, the open string sounds of the violin look like this:

You will see that the notes are placed in various positions on five parallel lines called a stave. Every line and space on the stave represents a different pitch, the higher the note, the higher the pitch.

The note on the left here is the G - string note, which is the lowest note on the violin. The note on the right is the E - string pitch, which is much higher.

The round part, or head of the note shows the pitch by its placing on the stave. Each note also has a stem that can go either up or down.

The symbol at the front of the stave is called a treble clef. The clef defines which pitches will be played and shows if it’s a low or high instrument.

Violin music is always written in treble clef. When notes fall outside of the pitches that fit onto the stave, small lines called ledger lines are added above or below to place the notes, as you can see with the low G - string pitch which sits below two ledger lines.

Once too many ledger lines are needed and the music becomes visually confusing, it’s time to switch to a new clef, such as bass clef.

The numbers after the treble clef are called the time signature. The stave works both up and down (pitch) and from left to right.

From left to right, the stave shows the beat and the rhythm. The beat is the heartbeat or pulse of the music. It doesn’t change.

The music is written in small sections called bars, which fall between the vertical lines on the stave called bar lines.

Some pieces have four beats in a bar, which means you feel them in four time, some have three, like a waltz, and so on.

The time signature shows how many beats are in each bar, and what kind of note each of those beats is.

The rhythm is where notes have different durations within the structure of the bar. This is where pieces can really start to get interesting.

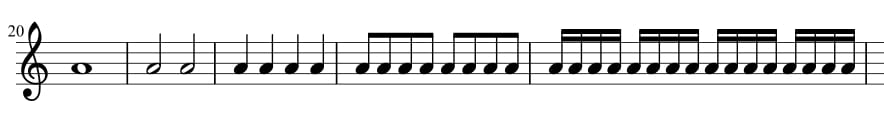

Here we can see a variety of rhythms.

Each of these bars has a value of four beats. The first of the notes above is called a semibreve. It lasts for four beats.

Each of these bars has a value of four beats. The first of the notes above is called a semibreve. It lasts for four beats.

The second is called a minim (or half note, in America) and each minim lasts for two beats. You can see there are two minims in a four-beat bar.

The third example is a crotchet or quarter note. Each crotchet is one beat long.

The fourth rhythm is a quaver, or eighth note, which lasts for half a beat, and the last note value shown is called a semiquaver or sixteenth note, and lasts for quarter of a beat, so sixteen semiquavers fit into a four beat bar.

The smaller notes are written in groups of four so they match up with the beat visually and are easy to read. Each note length has a corresponding symbol to show when there is a rest (silence) of that duration.

The time signature 4/4 shows that there are four beats in each bar (the top 4) and that each of those is a crotchet or quarter note (the lower 4).

The time signature 3/8 would show three (the top number) quaver, or eighth note, (the bottom number) beats in a bar.

As you put your fingers on the strings to play new notes on the violin, the music shows the pitch rising. So the first finger note on each string of the violin would look like this: The note after G on the G – string is called A and is played with the first finger.

The note after G on the G – string is called A and is played with the first finger.

The note after D on the D – string is called E, on the A – string it’s B and on the E – string it’s F.

The first finger in violin fingering is the index finger, unlike on the piano where 1 denotes the thumb.

There are other symbols which show pitch, one of which, the thing that looks like a hash tag, is shown above. This one is called a sharp and the full name of the second note shown on the E – string is F sharp.

You will see these symbols for sharps or flats in the key signature of nearly every piece. The key signature is placed between the treble clef and the time signature and shows you which key or tonality to play in.

As you add the other fingers, you can see below how the gaps on the stave are filled, until you are playing every first position note on your violin. As you build up your fingers one at a time, the pitches on the stave look like this:

The very last note here is played with the fourth finger on the E – string.

It is worth noting at this point that because the pitches of the violin strings are five notes or a fifth apart, each open string note after G can also be played with the fourth finger or pinkie on the previous string, so the A – string note, for example, can be played with the fourth finger on the D –string.

This seems a lot to remember but there are a couple of helpful memory tricks:

The notes in the spaces of the stave, in ascending order, are F, A, C and E, or FACE.

The notes on the lines are E, G, B, D and F. You may remember learning the mnemonic, Every Good Boy Deserves Fun.

You will soon begin to memorise which note corresponds to which sound and finger placement on your violin. Remember that when you learned to read, you were simultaneously studying writing skills.

Try downloading and printing this music manuscript paper, and practice writing out the notes as you learn to play them. Write out the open string notes and practice from your own copy.

Making the connection between writing, reading and playing will speed up and deepen the process of learning.

Soon the note reading will become habitual, and just as you don’t have to process every letter to read a word, you will begin to see the piece as a whole rather than having to read each note and work out where to play it.

As with any new skill, the more you practise and try it out, the more confident you will feel and the sooner you will be reading music fluently.

The articulation of sounds on the violin is much like the production of different consonants and vowels in speech, and the nuance in expression of tone. The many ways of articulating notes with the bow makes them speak in different ways.

Articulation in violin music is created using range of bowing gestures. These can give the violin an array of different sounds on any one pitch. These differences are mainly in the transient sounds at the beginning and end of the note, and in the length of the note and the attack of the bow. Various techniques of bow pressure, position of the bow (point of contact), angle of the bow and position and movement of the wrist, fingers and elbow are used to create different shapes in with the sound.

These techniques can be described as bowing patterns, or thought of in terms of tone qualities, speed, pressure and position of the bow.

The first articulations the violinist will encounter are the simple ideas of separate bows and legato. In separate bows, the direction of the bow is changed for each note, so each note occurs up bow, down bow, up bow, down bow and so on. In legato bowing, two or more notes are played in one bow stroke. Sometimes separately articulated notes are played within one bow stroke.

Legato bowing creates two main challenges. Firstly, the sound of the bow must not be disturbed by what the left hand is doing. An exercise such as the first study in the Schradieck School of Violin Technique is helpful for coordination of the left hand within a slur. This can be more complicated when a fingering during a slur involves a substantial change of position. A change of position not only requires a change in sounding point, the violinist will have to use the bow to help the left hand make the shift. By slowing down the bow stroke slightly and lifting the pressure whilst the left hand is shifting, a shift can be camouflaged without disrupting the legato flow.

The second challenge of legato bowing is where the slur involves any string crossing. A slight pressure of the bow as the string crossing is made will help bind the tone of the first and second note. Generally, the best technique for smooth string crossings within legato is to approach the second string gradually, so as the first note is slurred to the second, a double stop will sound momentarily. This double stop happens so subtly it is not possible to distinguish it, and only the desired note, aided by the slight bow pressure, is heard.

Where the bow changes back and forth between two strings several times in one bow stroke, it is easiest to keep the bow as close as possible to both strings at once whilst still making sure each note sounds clearly. String crossings like this are hardest at the heel of the bow because they require a subtle and active use of the right hand fingers. Practice studies for legato string crossings can be found in Exercise IV of the Schradieck tutor.

Détaché bowing can, in its simplest form, be described as playing with separate bows. However, the more advanced détaché stroke has a slight swelling at the beginning of the note, followed by a gradual lightening. This is created by adding a slight pressure at the beginning of the note without accenting it. When the stroke is played continuously the infection gives the impression of separation between the notes.

Portato bowing is very similar to détaché bowing and performed using almost the same technique. However, portato is a series of détaché strokes played with one bow stroke. This articulation is used to bring more expression to slurred legato notes.

There are many more advanced and subtle bow techniques, all of which create different articulation in the sound of the violin. Some of the more unusual and distinctive include:

Other more advanced bowing techniques can be learned to produce a huge variety of articulation, character and sound.

The Forty Variations opus 3 by Otakar Ševčík is a compact introduction to many bow strokes including collé and spiccato. Collé is a very important practice bowing, invaluable for developing control of the bow in all its parts. It is also musically useful, being incisive and short.

Spiccato is a bow stroke in which the bow is dropped from the air above the string and leaves the string again after each note. It is played mainly in the lower two thirds of the bow and can range from very short to fairly broad.

Articulation markings in music are indicated by various dots, lines and shapes attached to the note. Generally, a note with a dot above or below is played short, and one with a line is played long. These markings inform which gesture the violinist will make with the bow. A passage of quavers, for example, all articulated with dots, might be played with a spiccato bow stroke. The symbol > above or below a note indicates that the note is played with an accent.

A list of common articulation markings can be found here.

The extent of articulation and nuance possible with advanced study of bowing techniques is as broad as the range of language and expression of a skilled singer. This exploration of some of the basic concepts is only an introduction to the possibilities of violin articulation. Ask your teacher to show you some of the more detailed bowing skills, and use studies and repertoire to develop your vocabulary of sounds.

For more ideas on right hand technique and how the bow arm produces sound, read the ViolinSchool article on Tone Production.

Listening is one of the most important skills you can have. How well you listen has a major impact on your effectiveness at work, your relationships and your musical practice.

Listening enables you to learn, to obtain information, to understand and to enjoy, yet it can often feel like an abstract ability. Research suggests that most people remember only 25 to 50 percent of what they hear, meaning that whether you’re talking to a friend, listening to your violin teacher or listening to your violin practice, you’re paying attention to at most, half of what’s going on.

By becoming a better listener, paying attention to how you listen and what you are listening for, violin practice will improve, but good listening and its application in violin practice requires a high level of self-awareness, attention, positive attitude, flow concentration and critical thinking skills.

Listening in violin playing comes in many different guises:

First, prepare yourself to listen. Put other things out of your mind. If you notice you are thinking about what you’re going to have for dinner, allow the mind to re-focus on the music you are about to play, the sound you want to make and the shape of the musical phrase you would like to express. It is very easy to allow the brain to drift into autopilot.

Warm up by playing some long notes and slow scales. Really engage with the sound you are producing. Try to do so non-judgementally, just enjoying the variations of vibration and tone. As your body warms up, give yourself some images of colour, texture or objects, for example, a smooth piece of dark blue velvet. Visualise the feeling and the colour, and then play some notes with the same feeling. Really listen to your tone and the feelings you produce from the notes.

Practice focussed concentration. Break your violin practice into short bursts so you can really listen. The mental state in which you are fully immersed in what you are doing, known as flow or being in the zone, represents the deepest levels of performing and learning. In flow, the emotions are positive, energised and aligned with the task in hand. This level of positive focus is most likely to occur when you are practising with purpose; with a clear set of goals and progress, giving direction and structure to the practice, and with clear feedback; so having actually really listened to what you’ve just played.

It is important to find a balance between the perceived challenges of the music or technique you are practising, and your level of skill as you perceive it: You must feel confident in your ability to achieve what you want.

Broken down, this level of concentration can be achieved when you know:

If you are bored or anxious, it is very difficult to concentrate properly, and to listen to what you are really playing without negative preconceptions. Use visualisation, listen in your mind to what you want to do, listen to the results and enjoy the process. This is where your critical thinking skills will come in. Use the information gathered from listening fully to what you are doing to evaluate what you are doing and how you might develop it.

Full concentration, really listening to what you are doing, is more likely to produce the information and results you want than simply hearing what you’re playing.

Try breaking down what you hear into separate parts so you can listen more closely. Work on the rhythm, intonation, tone, phrasing and other musical ideas individually, and then start to put everything back together. Sometimes when you concentrate on the rhythm, the tuning will go funny, for example. Don’t worry about this; your brain is focussed on integrating your understanding of the rhythm. You can go back to the intonation later.

Allow your ears to listen to the sound in the whole room, not just to the sound coming from your violin. Imagine you have one ear at each side of the room. Sometimes it can be interesting to put an earplug in your left ear to hear the sound that is going into the space rather than the noise under your earhole!

Read the article about visualisation skills for more ideas and practice techniques.

You can use the ViolinSchool Auralia ear training software (included free with your ViolinSchool membership) to practice your listening skills and deepen your understanding of the music you are learning. Most music has three main ideas to notice: new melodies, repetition and variation. You can also look for colour, balance and texture, key (major or minor), rhythms and accompaniment. The more you understand about how your piece is put together, the easier it is to feel confident in how you want it to sound.

Listening to someone you admire playing the piece you are learning is one of the best ways to motivate yourself and understand the music. You can develop a mental map of the characters, colours and energies that make up your piece.

Listen to the piece as a whole and in small sections. It can be fun to listen to a phrase and then try to recreate the sounds and shapes you heard on the recording. Many beginner violin books and graded exam books now come with CDs. For children learning the Suzuki method, listening is one of the first skills learned. Suzuki encouraged his young students to listen to recordings of great violinists, and his method is based on the mother tongue ideal of repetition and imitation. Suzuki children normally start off playing the violin with a beautiful tone because they have listened so much to the sound of the violin. Ultimately, listening to the piece before and during study allows you to build a concept and an ideal of the music, and motivates your listening and your practice.

Recording your violin practice and performances and listening back is an extremely useful practice tool. Don’t listen back immediately if you feel it might be a negative experience. Record one day and listen back the next so you have a little distance from the process of “doing”. Often you will pick up on all sorts of things you missed. The violin is right under the ear and it can be difficult when you’re actually playing to pick up on things that are obvious when you are focussed solely on listening.

It can be easy to go into a lesson with a preconceived idea of what you can and cannot do. Your teacher will have a completely fresh perspective on what you are playing and will hear positive things and aspects you can work on, some of which you may think didn’t sound so good, or which you hadn’t noticed weren’t working. When your teacher is explaining something, don’t talk. Listen. Don’t interrupt or talk over them or you will miss vital information. You already know what you think; this is the time to take advice.

Listen to feedback in a positive way. Feedback that tells you why something isn’t working and how you can make it better is incredibly valuable; don’t let it depress you if your teacher isn’t constantly complimentary. Listen to the feedback and add it to your information banks. It would be much worse if nobody in your support network ever told you something didn’t work and it was only picked up in an important concert.

Playing with other people requires a whole new level of listening. Suddenly you aren’t just listening to your own sound, tuning and rhythm, you’re listening to the group sound and required to play in time and in tune with other people.

Have a look at the article about Ensemble Playing for some in depth ideas for playing with other musicians.

The whole point of playing the violin is to enjoy its sound. Without listening, there is no function to the music. Developing the conscious listening skills in practice that enable you to really express the music in performance is a really important part of practice and learning. Learning to listen when you practice, and to hear the elements of music as it’s performed, will heighten your enjoyment when you go to a concert, or when you hear birdsong, the wind in the chimney or the waves on the beach. You might even find you are listening and communicating better with others.

Start noticing your listening when you practice and see what else comes into your awareness through practising this essential skill.

One of the most crucial decisions to the performance and interpretation of any piece of music is the speed. Getting the speed right allows room for all the intricate levels of technique and expression to work; it creates the mood, tells the story and allows the music to dance.

When we play in an orchestra, the conductor indicates the speed of the piece with his upbeat and subsequent arm movements. In smaller ensembles, the speed of a piece must be decided between the musicians, and somebody has to lead. This is helped by everybody breathing together as the upbeat is given. In violin practice, we can use a metronome or our own sense of pulse, and choose a practice speed that allows us to work effectively.

The speed of a piece of music is called the tempo, which is just the Italian word for time. In fact, most of the words we need to learn in order to understand the speed and feel of the music we play are Italian. In the 17th century, when tempo indications were first used extensively, defined and standardised, many of the important composers were Italian, and these terms have remained widely used in music to the present day.

There tends to be no tempo indication in music written before this method came into common use. In Baroque music, conventions governing composition were so strong that the speed of the music is hardly ever indicated. When Bach wrote a Giga, it was understood what speed that Giga, or jig, was meant to go.

In Renaissance music, most pieces were understood to flow at a speed roughly the same as the human heart rate. The note value which corresponded to this pulse, known as the tactus, was defined by the time signature, so 3/4, 2/2 and 6/4 would indicate different speeds as much as a different musical emphasis.

Many musical forms, particularly those derived from dances, have their own tempo too, so no instruction is given in the music. When we see a waltz, minuet or tango, we understand the speed and mood from our knowledge of the dance, period and style.

The tempo of a piece of music is sometimes indicated by a metronome marking which is measured in beats per minute (BPM). The note value that gives the beat is specified by the time signature. For example in 4/4, the beat is a crotchet. The speed is dictated by the amount of time between beats, specified as a fraction of a minute. A metronome marking of crotchet = 60 means there is one crotchet beat per second, and a metronome marking of crotchet = 120 means there are two crotchet beats per second; so crotchet = 120 is twice as fast as crotchet = 60.

The metronome was invented by Johann Maelzel in 1816. Music written before the metronome became popular will only have metronome markings if they are editorial. One of the first composers to include these mathematical tempo indications himself was Beethoven, but his markings create more questions than answers; they are inconsistent or sometimes impractical, leading to the theory that his metronome didn’t work very well! The modern digital metronomes are much more reliable.

Despite appearing very specific, metronome markings are nearly always only an approximate guide. Depending on the time signature, your musical interpretation and even the acoustic where you are performing, the markings may not always be appropriate.

Most pieces of music are given Italian words as tempo indications. These words are much more specific in their descriptions of how a piece should go than a metronome mark, as they often give an indication not only of speed, but of the character and mood of the music. For example, whilst Presto means fast and Allegro also means fast, the Italian meaning of the word Allegro is joyous or gleeful, giving a new intention to the music.

Tempo markings are also frequently accompanied by descriptive words which give a deeper indication of how the music should sound.

The understanding and interpretation of tempo markings must be affected by when the music was written. Tempos have changed over the course of time, and some of the terms have switched places. A modern Largo is slower than an Adagio, but in Baroque music it was faster.

Let’s have a look at some of the most common words you will see:

Grave – slow and solemn

Lento – slow

Largo – slow and broad

Larghetto – quite slow and broad

Adagio – slow and stately, meaning “at ease” in Italian

Andante moderato – a bit slower than Andante

Andante – at a walking pace

Moderato – at a moderate tempo

Allegretto – moderately fast

Allegro – fast, quickly and bright

Vivace – lively and fast, from the Latin, vīvāx, literally meaning full of life

Presto – extremely fast (168–177 BPM)

As with dynamics, basic tempo markings can be adjusted in various ways:

Tempo can often fluctuate through a movement to give musical interest. Tempo changes are often written into the music, and there are specific terms for these too.

Composers often use expressive marks to adjust the tempo in the middle of a piece. Elgar is famous for his exacting instructions and some of his works have a different tempo marking every few bars!

Here’s what they all mean:

The overall tempo indication will always appear in large type above the stave, whereas tempo adjustments such as accelerandos or ritenutos generally appear below the stave.

After a change of speed, a composer may indicate the return to a previous tempo by marking a tempo or tempo primo. These terms indicate an immediate return to the main tempo of the piece.

Alongside the instructions which exist purely to give an idea of the speed, composers use a huge variety of descriptive words. The slow movement of Elgar’s String Quartet is given a metronome marking alongside which it is simply marked piacevole, which means peacefully. Given the context of Elgar’s music, this word conjures up bucolic interpretations of this peace and gives a clear idea of his intention for the mood. It would mean something different from another composer.

The number of words used to give the character sometimes precludes understanding without the aid of an Italian dictionary, but many of them are quite similar to English words. Here are a few examples of descriptions that often accompany tempo markings:

Although Italian is the most common language for tempo and expression markings, many composers write in their own language. Debussy, Ravel and Rameau wrote their instructions in French, and Beethoven, Mahler and Strauss used German.

Take time to learn as many tempo words as you can, and notice which other words regularly appear at the top of your music. Listen to the music you are learning, and to other music by the same composer or from the same period of musical history. Watch dancers performing modern and ancient dances and listen to folk music.

Tempo markings give a clear academic definition to the speed of a piece, but only practice, immersion in listening and experience will really help you to choose the speed which makes the music work best for you and your audience.

violin and ageViolin an

The beneficial effects of learning a musical instrument are well documented in young children, and the violin has seen its share of child prodigies, but how does the relationship with the instrument change as the player gets older, and is it ever too late to start learning?

The beneficial effects of learning a musical instrument are well documented in young children, and the violin has seen its share of child prodigies, but how does the relationship with the instrument change as the player gets older, and is it ever too late to start learning?

Even the youngest children will respond to music. Shinichi Suzuki, Japanese violinist and father of the Suzuki method of teaching, tells a story in his book Nurtured by Love, about a five-month-old baby called Hiromi.

Hiromi had grown up listening to her older sister learning the violin, and her sister had been practising the Vivaldi A-minor concerto. Suzuki recalls, “When everyone was quiet, I started playing a minuet by Bach. While I played, my eyes did not leave Hiromi’s face. The five-month-old already knew the sound of the violin well, and her eyes shone while she listened to this piece that she was hearing for the first time. A little while later, I switched from the minuet to the Vivaldi A-minor concerto, music that was played and heard continuously in her home. I had no sooner started the piece when an amazing thing happened.

“Hiromi’s expression suddenly changed. She smiled and laughed, and turned her happy face to her mother, who held her in her arms. “See – that’s my music,” she unmistakeably wanted to tell her mother. Soon again, her face turned in my direction, and she moved her body up and down in rhythm.”

Suzuki’s method of teaching the violin begins in infancy. Based on the observation that every child is fluent in his or her own language, Suzuki believed that ability is not a matter of inherited talent, but of correct teaching, environment and encouragement.

According to Carolyn Phillips, former Executive Director of the Norwalk Youth Symphony Orchestra, learning music in childhood helps develop the areas of the brain which are involved in language and reasoning. Musical training physically develops the part of the left-brain that is known to be involved with language. It also increases the capacity of the memory. The parts of the brain that control motor skills and memory actually grow.

Phillips also explains in her article, Twelve Benefits of Music Education, that there is a causal link between music learning and spatial intelligence, which is the ability to perceive the world accurately and to form mental pictures of things.

Children who learn a musical instrument have been proven to be better creative learners and problem solvers. In his book Always Playing, Violinist Nigel Kennedy, former enfant terrible of the Classical Music world, describes his feelings about his early schooling: “I guess something like 80 per cent of what I was formally taught at my schools, particularly at the Menuhin [School], I reacted to badly, but that reaction led me to trying my own alternatives and it is always such a buzz when you see your thinking work out.”

Music also gives the player an internal glimpse of other cultures and teaches empathy with people from those cultures. Every piece of music has a cultural and historical back-story. When children come to understand different cultures through music, their development of empathy and compassion, rather than a selfishly orientated motivation, provides a bridge across cultures and leads to an early respect for people of different races.

Learning an instrument teaches the value of sustained effort. It teaches teamwork, responsibility and discipline. In an ensemble of any size, players must work together for a common goal and commit to turning up to rehearsals on time, having prepared the music. This requires time management, organisational skills and social skills, a focus on doing rather than simply observing and a willingness to conquer personal fears and take risks.

Most of all, learning a musical instrument is a means of self-expression. In Western society the basics of existence are fairly secure. The challenge is to make life meaningful and to reach for a higher state of development. Every human being needs at some point in his or her life to be in touch with his core, with what he is and what he feels. Having an outlet for self-expression leads inevitably to higher levels of self-esteem.

A child will start learning the violin for many reasons, but the violin is an instrument that can appeal greatly. It is small and lightweight, immediately accessible and available in different sizes so even a tiny child can pick up his violin easily. The violin is also a very personal instrument. Each violin looks similar, but no two sound the same, and even the same violin played by two people will sound different. This physical attraction to the violin is what leads a small child who has just begun learning to take his violin to bed with him like a teddy bear.

The violin is also an instrument that seems to attract child prodigies. Mozart was a child prodigy, as were Menuhin, Zukerman, Perlman and so many others. The pressure on these children can be enormous. Many don’t have normal childhoods. Paganini was apparently often locked in his room for hours by his father and forced to practice; a discipline which led him to serious problems with alcohol by the time he was 16.

Child “genius”, violinist Chloe Hanslip, interviewed in the Telegraph in 2007, commented, “I couldn’t be a normal child. Not properly normal, because I’m a classical violinist.” In the same article, Jennifer Pike, who won the BBC Young Musician of the Year on violin in 2002, aged just 12, explained in a more balanced way that an intensive musical education doesn’t suit everybody.

This comment is borne out by the experiences of Julian Rachlin, who won the Eurovision Young Musician of the Year in 1988, when he was 13. He went on to become the youngest ever soloist to perform with the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra. By the time he was 20, Rachlin had lost his confidence so badly it nearly ended his career. He went to study with Pinchas Zukerman, himself a former child prodigy. Zukerman helped him understand he had to develop his career path at his own pace.

Although in the instance of child prodigies, the motivation for progress often comes from the child, the conventional view is that they often end up as adults with broken lives and unfulfilled dreams. The American violin virtuoso, Itzhak Perlman, said in an interview with the New York Times that many things could go wrong with prodigies, particularly those whose parents had suspect agendas, that is, they wanted to achieve success through their child.

Shinichi Suzuki had a poor view of such parents. In Nurtured by Love he tells the story of a child whose mother had come to him with the question, “ Will my child amount to something?” Suzuki felt this was an offensive question and replied, “No. He will not become ‘something’.” He explains, “It seems to be the tendency in modern times for parents to entertain thoughts of this kind. It is an undisguisedly cold and calculating educational attitude.”

Suzuki told the child’s mother, “He will become a noble person through his violin playing… You should stop wanting your child to become a professional, a good money earner... A person with a fine and pure heart will find happiness. The only concern for parents should be to bring up their children as noble human beings. That is sufficient. If this is not their greatest hope, in the end the child may take a road contrary to their expectations. Your son plays the violin very well. We must try to make him splendid in mind and heart also.”

The ideal, as Julian Rachlin found, is that musical development should compliment personal growth; that is, not just educational growth but the development of the whole person. The relationship with creativity is intrinsic to the relationship with the self. As one grows, the other will become surer.

Watch this video of 11-year-old Sirena Huang, presenting a TED Talk on the technology of the violin, in between beautiful, accomplished performances. She has worked very hard to reach this level, but the main aspect that shines through is her enjoyment of what she is doing, and the need to share it; the fundamental human need to communicate.

A child might begin the violin because he likes the sound, knows someone else who plays or because his parents decide he should learn. But what if you are considering learning as an adult? Is it too late?

In her book Making Music for the Joy of It, Stephanie Judy sets out to encourage adult beginners. The first sentence in the book reads, “Welcome! You’ve chosen a wonderful time to start making music.”

Judy explains, “As an adult beginning musician you have many advantages over a child in the same situation. Your primary advantage is that you are in charge…Maybe you’ll regret that you didn’t start sooner, but that regret is a pale rival to your freshness and enthusiasm. You are not just fulfilling a personal fantasy; you are answering a great human longing.”

The most important prerequisite to beginning the violin later in life is to feel at ease with making music. Many adult beginners feel awkward and overwhelmed by the physical challenge of learning, but feeling at ease has more to do with clearing away self-doubts than it does with holding the instrument. Once you begin to get rid of doubts about your musical self, you have cleared the path for progress.

This is not only true for beginners, it is very pertinent for players who have been playing for many years, perhaps since childhood, but whose relationship with their instrument has always been guided by someone else; a teacher or a parent. Even at a professional level, as a violinist continues to develop, old self-doubts must be cleared in order to free the way for new musical expression and integrity. This then begins to work in the other direction. As you begin to understand your musical and creative self and free up mental blocks, this understanding transfers in a positive way into other aspects of your life. Even at a professional level, a violinist never stops learning.

As an adult beginner you may feel you should have started as a child, but the fact is, for whatever reason, you didn’t. It’s also true that all your experience to this point in your life has brought you to wanting to play. You must begin where you are today.

Playing the violin is a holistic activity. It involves the whole body but also the deeper self, self-doubt and complex experiences and emotions.

Judy says, “Adults often help themselves along the road of musical understanding more quickly than children because of their deeper experiences, both of music and of life.”

The reasons an adult might want to start learning the violin are very different from the reasons a child might have. Adults often get to a point where they want something that makes new demands on them. Sometimes it’s a need to express artistic energy and communicate. It can be a yearning for some activity that needs total mind and body focus, total involvement in a world where we constantly multitask. Learning the violin can offer stress relief and perspective as the music draws you into the present moment. It is a social activity, with the chance to play fantastic orchestral and chamber music repertoire at any level.

Whatever age you are, five or 75, the important ingredients to success are the same: Passion, patience, time to practice and perseverance. We would never ask if it is too late to learn to paint, or to learn a language yet somehow there is a belief that unless you begin the violin as a toddler it is too late. Not so. There is an enormous benefit to engaging the brain in new activities throughout all the stages of life.

Here is an example from www.uncorneredmarket.com, from a selection of inspiring stories for elderly people.

“You are never too old to learn.

Andrew, one of my grandfather’s colleagues from when they both worked in India in the 1960s, now lives in my grandfather’s retirement complex.

He had to give up his violin lessons when he escaped Hungary in 1937 as his family began facing persecution for being Jewish.

“It had been 75 years since my last violin lesson. I wanted to play violin again, but I sounded awful. I decided I needed lessons.”

Earlier this year, he began taking violin lessons again. We asked how things are going.

“I’m progressing pretty well. It’s fun to play again,” Andrew chuckled.

He’s scheduled to play a Christmas concert this week. I imagine there are many more in his future, too.”

Finally, whatever your age, it’s important to maintain your physical wellbeing in order to keep playing at your best. Read the article on the body for some ideas and tips.

Never practice without warming up, and take regular, gentle exercise such as yoga to keep your joints mobile. The DVD Yoga for Musicians shows some simple and effective stretches to release tension and build muscle tone.

The British Association for Performing Arts Medicine has lots of information about health resources for musicians on their website, including a useful chart of warm up exercises.

So whatever your age, keep playing, keep learning and keep enjoying all that the violin has to offer.

The word dynamics in music refers to the volume of the sound or note. Dynamics are part of the vast array of musical expression and interpretation marks written into music. Dynamic markings do not represent specific values of volume; they are relative, depending on many factors, from the size of the room in which you are performing to the style or historic context of the piece.

Dynamic markings are generally written as shortened Italian terms. The basic volumes are quiet, which is written as the letter p, representing the Italian word piano, and loud, the Italian word forte, written as f. Within piano and forte there are grades of volume, including mezzo piano which is louder than piano and mezzo forte which is quieter than forte. Sometimes you might see other descriptive words with the dynamic marking, for example the word più, which means more. When you see più piano it literally means more quiet. At the extremes of dynamic are pp, pianissimo, which is very quiet, and ff, fortissimo, which is very loud. You can see multiples of the p or f, such as fff or ppp when the composer wants a really strong volume effect.

Changes of dynamic are also marked in Italian. Subito forte, for example, means suddenly loud. A forte piano, written fp, is where a note begins forte and suddenly becomes quiet. Sforzandos and accents are notes which have strong beginnings. Crescendos and diminuendos, which are where the music gets louder or softer, are marked as shortened terms, cresc. or dim, or as ‘hairpins,’ which look like this:

The elements of violin technique relevant to the successful realisation of dynamics are the same as the three fundamentals of tone production.

Starting with the basics, this video shows how the dynamic movement of the body; arm weight and back muscles; can be applied to the violin to make a good tone:

The way the bow arm is used affects the tone quality and the volume of sound. The three factors that interplay are the amount of weight placed into the bow, the speed at which the bow is used and at which position between the fingerboard and bridge the bow is drawn.

Within these parameters, the mechanics of playing forte and piano on the violin are very different from each other. The bow hold must alter subtly to effect every change in volume.

In piano, where you might want to create a transparent, quiet sound, the first finger moves towards its base joint in the way it touches the bow stick, and the other fingers come slightly off the stick. When the bow needs to settle into the string more to play forte, where more breadth of sound is required, the index finger readjusts. The wrist will have a feeling of pulling the bow and the first finger will slightly spread away from the second and feel a closer contact with the stick, nearer to its middle joint.

Greater speed in the bow stroke per beat means greater energy transmitted into the violin. If the pressure, which is the other energy-producing factor, remains the same, a change in speed will alter the dynamic. Increasing the speed of the bow makes the sound louder; decreasing it creates a softer sound.

For a note that requires the same dynamic throughout, the best and simplest way to use the bow is with an equal speed for its whole length. Equal speed means equal bow division. For example, if there are four quavers (quarter notes) to be played within one bow stroke, each note should be played with one quarter of the bow. If there is a dotted crotchet (dotted half note) and a single quaver (quarter note), the dotted note will be played with three quarters of the bow and the quaver with the remaining quarter. It is tempting to set off with too fast a bow stroke which means that the bow runs out towards the end of the stroke. This makes sustaining an even dynamic impossible. Practice long notes of four beats with the metronome at crotchet = 60, dividing the bow equally into quarters with the beat. Make sure that after two beats you have not passed the halfway point. Another way to practice slow bows is to gradually work up with a metronome to long notes of 30 seconds per bow.

The volume of the violin also depends on the weight of the bow into the strings. The bow is not equal at each end. The frog is much heavier than the tip, and also supported by the weight of the arm, whereas the tip of the bow is much lighter and used by the arm in almost full extension. When an even dynamic is required, the pressure used must be uneven to compensate for this difference. At the frog, the volume comes from the weight of the arm into the thumb and the third and fourth fingers. In the middle of the bow, the weight comes from the arm into the middle fingers and thumb, which requires a free upper arm and shoulder without excessive tension. To get extra volume at the tip of the bow where the arm is extended, use flatter bow hair, so there is more hair in contact with the string, and transfer additional weight from the middle and fourth fingers into the first and second fingers. The wrist and hand move down slightly and help the weight transfer.

There is a constant fluctuation and balance within the hand with every bow stroke, between the first and second, middle, and third and fourth fingers and the thumb. See if you can draw a long slow bow, starting at the frog with only the thumb and fourth finger on the bow. As you move towards the tip, transfer the weight into the middle fingers, lift off the fourth, and let the weight gradually transfer into the index finger, until you are at the tip of the bow holding it between only the index finger and thumb. Reverse the process, ending back at the frog with only your fourth finger and thumb on the stick.

One tricky aspect of technique is where bow division is not straightforward, for example where there is a recurring rhythmic pattern of long and short notes. To stay in the same part of the bow whilst playing a long, short, long, short rhythm, the speed of the bow for the short note will have to increase. This change of speed will create an increase in sound, so the shorter note is louder. To make the dynamic even between the two note lengths, it is necessary to adjust the pressure. By lightening the pressure of the bow on the short note, you can maintain a steady tone.

Often though, the dynamic is not meant to be even. Accents, crescendos and other expressive dynamics give subtle nuance to phasing and interpretation. Constant tiny manipulations of the bow occur to produce changes in speed and pressure.

Experiment with different degrees of pressure. Notice that too much pressure actually prevents the string from vibrating and crushes the sound. Extreme pressure can also have the affect of altering the pitch, and if you press really hard you will hear a sound an octave lower than the note you are playing.

A sforzando, written sfz, is an accent at the start of a note, followed by a sustained draw for the value of the note. It is a similar stroke to martelé, which is a strong, expressive detached stroke. The volume of the sforzando depends on the dynamic level in the phrase where it is played. The weight for the accent comes from a first and second finger bite on the bow and thumb pressure against the frog.

An accent, shown with this symbol > above or below a note, is a similar articulation to the sforzando, but with a lighter accent at the beginning of the note. Immediately after the accent, the weight is released and the bow drawn in a legato style for the rest of the note. Again, the amount of accent depends on the dynamic level. A loud accent will naturally be stronger than one in piano. The weight comes from the first and second fingers on the bow and thumb pressure against the frog.

The third element of technique that determines the creation of dynamics is the sounding point; the position of the bow on the string between the bridge and the fingerboard. The violin will produce a louder, more vibrant tone closer to the bridge, and a softer, less distinct sound near the fingerboard. A flat bow, pulled parallel to and near the bridge will bring out a full, loud sound.

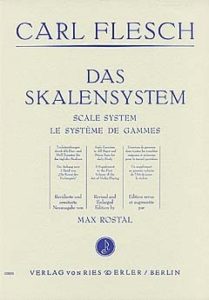

As explained in Simon Fischer’s book Basics, the two famous violin teachers, Carl Flesch and Ivan Galamian, both divided the area between the bridge and the fingerboard into five sound points. Flesch called them:

Different sound points combined with different bow speeds and pressures create more subtle variations of tone and dynamics. Whatever amount of speed and pressure you are using, there is a sound point where the string will vibrate more and the note will sound more vibrant.

Slower, heavy bows on sound point 2, which is near the bridge, will produce lots of volume. Fast, light bows on sound point 5 will be quiet.

It is possible to use the sound points to crescendo and diminuendo with rich and expressive tone. Glide the bow towards the fingerboard or pull it towards the bridge in such a way that it never loses its right angle relationship to the string, like the gramophone needle gently moving from one ring of the record to the next. An alternative method is to slightly angle the bow, using the non-parallel angle to move nearer to the bridge or fingerboard within the bow stroke.

The performance of dynamics, which are relative and not absolute, depends on many factors. Galamian explains in his book, Principles of Violin Playing and Teaching, “Anybody who talks to a few people in a small room need not even raise his voice…Speaking in a large auditorium, however, to an audience of thousands, is obviously an entirely different matter. The speaker will have to speak louder, slower and more clearly. These are obvious things, yet it is strange how few are the instrumentalists who realize that the same things apply to them when they perform in public.”

The way dynamics work within a piece change depending on the size of the hall and audience, and on the acoustic. If the hall is very resonant and not too big, not much needs to be done, but if the acoustic is dead and dry, or the hall is very large, all of the dynamics need to be upgraded. This is easy enough in the piano and pianissimo passages, but when loud dynamics such as forte and fortissimo occur, you need to be flexible with bowings, so you can change the bow as much as necessary to get the required volume without forcing the tone.

Dynamics are also relative depending on your role in a performance. As the soloist in front of an orchestra, your dynamics will be augmented, whereas if you are sitting in the orchestra, you should never play louder than the other players or your sound will not blend. As the second violinist in a quartet, you need to project your sound through that of the first violinist and cellist who are not only sitting further forward, they are playing at pitches which naturally project better on their instruments. It is important in chamber music to know the score; to understand what role your part has. If you have a melody or important countermelody, the relative dynamic of your part may be more than someone else’s, even though you both have the same dynamic marking. The same goes if your part is accompanying. You may need to play more quietly.

Let’s recap with a short video demonstration of different dynamics on the violin:

You might also find this printable worksheet helpful (courtesy of www.teachervision.com) to make sure you recognise the dynamics in your own music.

[gview file="https://www.violinschool.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/worksheet.pdf"]

Sight Reading for Violin

“The ability to sight-read fluently is a most important part of your training as a violinist, whether you intend to play professionally or simply for enjoyment. Yet the study of sight-reading is often badly neglected by young players and is frequently regarded as no more than an unpleasant sideline. If you become a good sight-reader you will be able to learn pieces more quickly and play in ensembles and orchestras with confidence and assurance.” Paul Harris, author of the Improve your sight-reading series.

Sight-reading is a really important skill. We sight-read new pieces in orchestra and duet rehearsals, we get sight-reading tests in exams and auditions; if you can’t sight-read, learning a new piece, or even choosing which piece to learn, is an arduous task. An ability to sight-read well opens up opportunities to enjoy ensemble playing and take charge of your own learning. Good sight-readers are more versatile performers because they are able to assimilate new music and diverse styles very quickly, and to perform with minimal rehearsal time. Learning to sight-read well should be at the top of every violinist’s list of priorities.

The main problem with sight-reading is that we start to see it as separate from our other musical skills and even our basic musicianship. Faced with a piece of sight-reading, we shut down our brain to all of the things we have learned and enjoy about the instrument, and panic.

Fundamentally, sight-reading is the skill of reading music, and how that reading transfers into movement and sound. Sight-reading is a skill, and it is true that the more you do it, the more fluent you will become, but there is no point spending hours trying to improve unless you understand the elements of the skill. It is essentially a mental activity, the message travelling from eyes to brain to fingers, and it is important not to try too hard or you’ll get in your own way! Really successful sight-reading is relaxed, calm and musical.

It is important to practice sight-reading regularly as part of your practice. Once you have grasped the basic concepts, the skill needs constant reinforcement to instil good habits. If you can’t bear to practice on your own every day, arrange to meet friends for ensemble playing and read through new pieces with them.

Only accessible material enables you to acquire the habits that will lead to fluency. Don’t choose to sight-read complex material, start with really basic music and build up to more complicated pieces gradually. Get as many sight-reading books as you can so you don’t run out of material. Paul Harris’s graded series, Improve Your Sight-reading is excellent, because it starts by breaking down the basic components of pulse, rhythm and melody, and the exam boards have books of specimen tests available. You could even use the pieces or sections of pieces you don’t know in any book you are working from. As a rough guide, it’s an idea to start learning to sight-read using music which is much easier than your current repertoire.

Practice sight-reading slowly; learn the positions of the notes on the stave and how they relate to your left hand finger patterns. Scales are great for learning finger placement. Make sure you know some basic theory concepts such as key and time signatures. Don’t be fazed if you come across something you’ve not seen before. That happens to everyone. Just find out what it is.

The first thing to do when faced with a piece of music you haven’t seen before, because that’s all sight-reading is, is to prepare the piece.

As you become more experienced, this process will speed up and you will be able to gauge most of the information you need by visually scanning the music before you start.

Successful sight-reading is largely a matter of good quality concentration. Your mindset and focus as you look at the page is the most important factor. Notice your eyes. Visual steadiness is crucial. Relax your eyes and don’t let them fidget and flit about, losing connection with what you are doing. Instead of going through the motions of reading, really focus. True concentration is difficult to maintain for long, but you don’t have to work hard, merely practice awareness. The second you notice your concentration has gone, you have already refocused yourself.

Problems generally arise when we are not ready for the notes as they arrive. Your eyes are looking at a note and you are also playing that note, and sometimes it’s happening so fast that your brain can’t process the information. Then you start to feel that blind panic which makes you hate sight-reading. The trick is to continually read ahead. Keep your eyes moving a few beats in front of where you are playing. Sight-reading in this respect is actually the process of visually memorising short snippets of music you are about to play whilst playing something else. This allows the fingers to be ready for the notes as they arrive, and suddenly you are playing fluently.

Reading ahead enables you to look at the music in bigger chunks. Instead of looking at each note as a separate event, you start to see how its rhythm fits into the beat, and melodically where scale and arpeggio patterns appear and how other intervals fit in.

Don’t react to mistakes. As soon as you give too much attention to a mistake, your concentration is no longer on what you are doing, and the chances are you are just about to make another mistake, and another. Decide to play all the way through without stopping. Keep going at a steady tempo and don’t worry about a dropped note. Imagine how quickly an orchestra would fall apart if every player who made a mistake hesitated or went back to correct it. Soon nobody would be in the same place at all. Prioritise. If on your first try you are able to keep the pulse but play all of the wrong notes, that’s a good start.

So as you prepare to play the piece remember:

Sight-reading is simply the process of playing a piece of music you haven’t seen before. Don’t separate it from your other musical skills in your mind; approach it with enthusiasm, curiosity and confidence. And now you have the tools to learn how to sight-read, never dismiss sight-reading practice as dull and unnecessary. It is one of the most fundamental skills a violinist needs.

Search “Learn Violin at Home” online, and you’ll be overwhelmed with resources; video courses, self-teaching plans, books, forums and advice. The violin is a notoriously complex instrument. Is it possible to learn it from home, essentially self-taught, or is there another aspect to learning from home which is more valuable when balanced with lessons?

There is some evidence to suggest it should be possible to teach yourself the violin. Young children learn by watching others, by demonstration and emulation, and research with animals (Byrne, 2003) has shown that even apes are able to acquire elaborate skills by imitation. Many folk musicians and guitarists are described as self-taught, though they have not necessarily learned in isolation. Guitarist Eddie Van Halen is self-taught, but musicians like him are an exception. For every success, there are thousands of people who end up as examples of bad habits and an instrument in the attic.

Learning violin is an intricate process. If you can’t afford to pay for lessons there are lots of free resources, but be wary. If you have a good ear, an analytical mind and good body awareness it is possible to learn the basics, but there are many details you can get wrong without a teacher. There are also a lot of people selling or promoting resources online who don’t actually know what they are doing, and as a beginner it’s impossible to decipher good from bad practice. Wikihow, for example, has a page titled, “How to Play the Violin,” which promises all you need to know in 14 easy steps, illustrated with pictures like this one, which is an astonishing illustration of poor posture and left wrist over-extension.

Feelings on the subject run high. Matt Molloy, a contributor on the ABRSM forum, puts it this way: “Can anyone tell me how to teach myself a set of extremely fine motor skills and artistic ideals whilst paying attention to loads of small details which could lead me down a nightmare path of bad habits and possible injuries…?”

Guitar teacher Jamie Andreas, who runs the website guitarprinciples.com has this to say about self-teaching on her instrument:

“Let's get a few things straight right at the beginning. Let's really look at this question, "should I take guitar lessons?" I have to tell you, whenever I hear a beginning player ask that question it makes me laugh. It's like a five-year-old saying they want to be a doctor or lawyer when they grow up, and asking if it would be a good idea if they went to elementary school! The mere asking of the question shows how much the person asking doesn't have a clue about what they are getting into, and how best to get into it.

“When I hear this question, I think "why on earth would it ever be a bad idea to learn a very complicated subject from someone who knows a whole lot more that you do, and has years of experience with the subject?" Why on earth would it ever be a bad idea, before beginning a journey to an unknown place, to ask for help from a guide, who has traveled the route many times? The very fact that someone is asking the question shows they don't understand how the whole process of the development of talent works.